India’s economy is at a crossroads. As economic momentum in China declines, The Economist Intelligence Unit predicts that India will be Asia’s fastest-growing economy between 2018 and 2022, carving out more influence in and importance to the global economy. World Bank data support that prediction, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth rising from 5.5 per cent in 2012 to 7.1 per cent in 2016. But while its economy may be experiencing robust growth, India still faces many challenges to ensuring that rate of growth can be maintained: demographic demands; energy and environmental concerns; insufficient infrastructure; concern over being left behind in the digital age; and a frenetic economy with high barriers to entry. Once poised to rival China, India’s GDP relative to that of its northern neighbour has slid continuously for the past 20 years.

Demographics: Dividend or Curse?

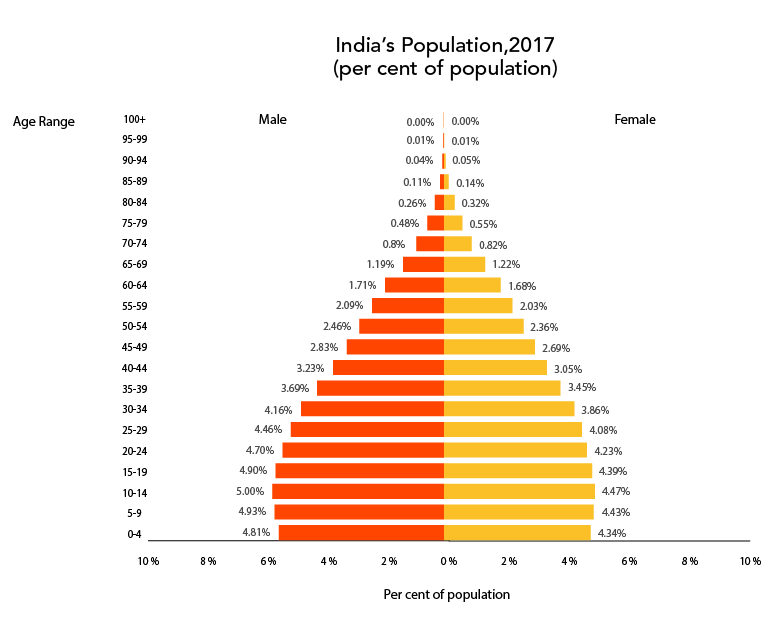

Like other developing economies, India’s population has undergone profound change in recent years. World Bank data shows that life expectancy has risen and child mortality and fertility rates have fallen dramatically, and poverty has been halved, from 38.2 per cent in 2004 to 21.2 per cent in 2011. 550 million Indians will be defined as middle class by 2030, according to HSBC.

India’s healthier and wealthier population is producing a youth bulge that will yield a demographic dividend in the decades to come. But demographic change also presents a challenge. According to the OECD, one million workers are entering the labour force each month, and opportunities need to be provided for them, but one-third of youth are neither employed nor in education or training. The government says that GDP growth will need to reach double digits to support the influx of workers into the economy. India’s massive population is also putting pressure on the government to provide adequate social services, but in many sectors, such as health care provision, India lags behind other countries.

Satiating Energy Demand in the Face of Environmental Challenges

India will need to meet its rising energy demands if it is to reach its economic growth targets and satisfy the needs of its population. Consumption has more than doubled since 2000, and though incidents such as the blackout that afflicted 600 million people in July 2012 are now rare incidents, 240 million people remain without access to electricity. India is expected to account for a quarter of the rise in global energy demand to 2040 – more than any other country.[1]

Coal has long been the backbone of India’s electricity-generating infrastructure, and currently accounts for 70 per cent of generation capacity. The damaging impact of India’s dependency on coal is demonstrable – 11 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world are in India. To meet demand while combating health and climate change concerns, India has embarked on a bold plan to expand capacity with renewable energy. India wants to install 175 gigawatts of renewable energy by 2022, up from 37 gigawatts in 2015. But electricity distribution companies are in a precarious financial situation and India’s energy regulatory structure is arcane.

Bridging the Infrastructure Gap

India’s infrastructure has long been considered rickety, inefficient, and unreliable. The rail network handles about eight billion passengers a year, but has barely expanded since India gained independence in 1947.[2] India also has one of the largest road networks in the world, but highways account for less than two per cent of the network.[3] One study by the Indian Institute of Technology Madras estimated that congestion cost the economy of New Delhi alone US$8.6B 2015.

Much of India’s infrastructure deficit can be attributed to the country’s litigious land-acquisition process. Property rights are strong in India, so land for infrastructure development cannot simply be expropriated. States also have a relatively high level of authority, so national projects requiring inter-state co-ordination have a hard time getting off the ground. Farmers are also an influential voting bloc, so long-term projects over multiple election cycles that impact their land and livelihood are difficult to implement. India’s finance minister Arun Jaitley has stated that India will need US$1.5T in infrastructure investment over the next decade to sustain its current rate of economic growth.

Going Digital

Around 900 million Indians now have mobile phones, and their ubiquity has been beneficial. For example, the Unique Identification Authority welfare delivery system, known informally as Aadhaar, is a system that links mobile phone numbers and bank accounts with a biometric identification system, allowing welfare payments to be delivered directly to beneficiaries. The expansion of the system has made 1.1 billion enrollees “visible” to the state.

Internet use is low, but booming. The internet penetration rate was only 33 per cent in 2017, but is expected to reach 50 per cent by 2020 as smartphone ownership proliferates; 500 million Indians are expected to have smartphones by 2020.[4] However, India risks not exploiting the opportunities that greater internet use presents. India is expecting e-commerce to become a major economic pillar. Two local firms, Flipkart and Paytm, have raised hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital, and Amazon is investing billions of dollars in India. However, according to The Economist, only 5 to 10 per cent of the population actively shops online, and growth has been below expectations.

Looking Forward

A few years ago, India risked squandering its monumental social and economic progress; however, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected in 2014 on a platform of addressing India’s macroeconomic challenges, Indians voted for economic reform. In the four years since the election, Modi has made some progress, such as tax reform and opening sectors of the economy to foreign investment, but much still needs to be done to meet the population’s burgeoning desires.

[1] India Energy Outlook. International Energy Agency, 2015.

[2] “India’s Once-Shoddy Transport Infrastructure Is Getting Much Better.” The Economist, 27 July 2017.

[3] Kaul, Vivek. “India's $100bn Road Building Gamble to Boost Economy.” BBC News, 28 Oct. 2017.

[4] “Internet Penetration in Rural India Abysmal: Report.” The Economic Times, 29 Sept. 2017.

Click here to download our digital chapbook of the entire Inside India series, or read our blogs, below . . .

1. The Path to Becoming an Economic Juggernaut

2. What Has “Make in India” Made for India?