Education is often associated with liberal opinions on a range of issues. To understand how education affects Canadian attitudes toward Asia, data from the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s 2016 National Opinion Poll was analyzed based on three education categories: those with some high school, a high school diploma, or equivalent; those with a college diploma or university certificate below the bachelor’s level; and those with a bachelor’s or post-graduate degree. The findings indicate that education has a positive effect on openness toward other countries.

Feelings Toward Asia

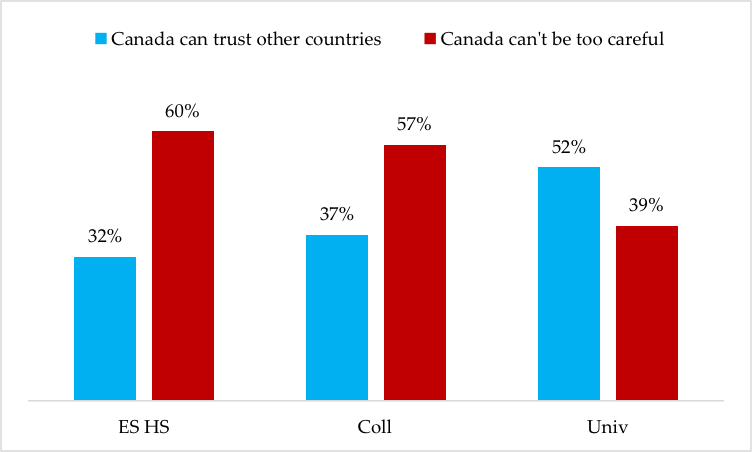

When asked if Canada can trust other countries, or whether Canada cannot be too careful in dealing with other countries, 52% of those with a bachelor’s degree or higher said that Canada can trust other countries. On the other hand, 60% of those with a high school diploma or some high school, and 57% of those with a college diploma or university education below the bachelor’s level, said that Canada cannot be too careful.

Q: Generally speaking, would you say that Canada can trust other countries, or that Canada can’t be too careful in dealing with other countries?

Note: Respondents who answered “Don’t know” are not included.

ES HS: Some high school, high school diploma, or equivalent

Coll: Registered apprenticeship or other trades certificate or diploma; college, CEGEP, or other non-university certificate or diploma; university certificate; or diploma below bachelor’s level

Univ: Bachelor’s degree or post-graduate degree above bachelor’s level

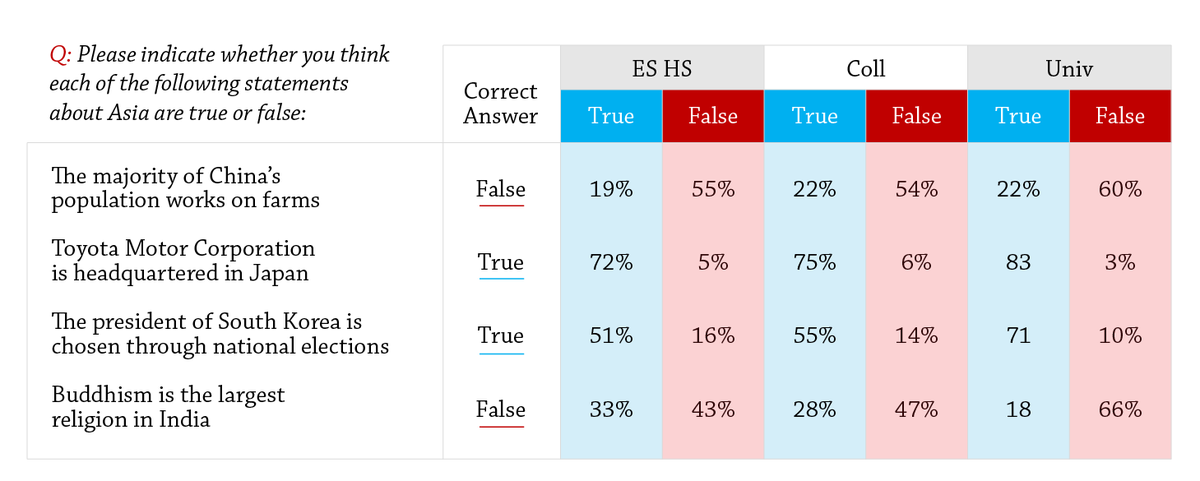

The differences in attitudes may be linked to different levels of knowledge. To gauge their level of awareness, Canadians were given a list of statements about Asia, and asked to indicate whether they thought the statements were true or false. Breaking down the responses into different education categories, we see that those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more knowledgeable about the facts.

Note: Respondents who answered “Don’t know” are not included.

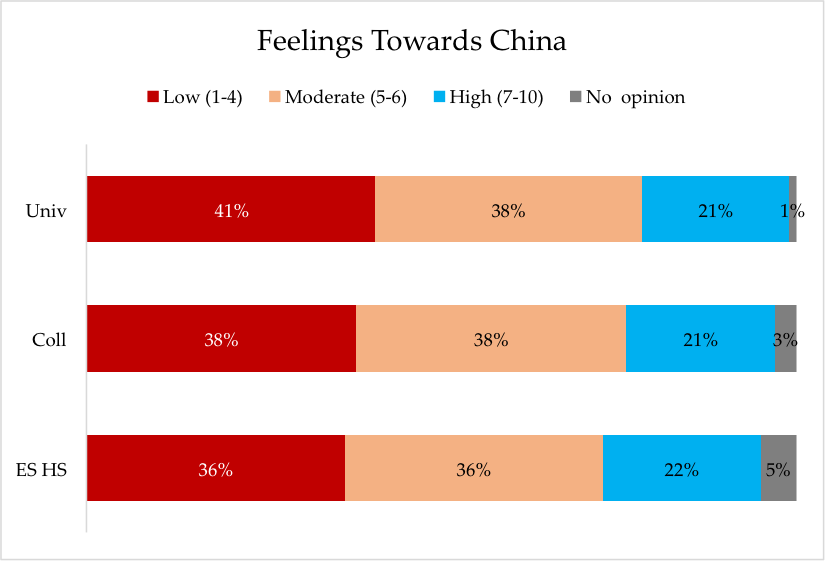

University-educated individuals are also warmer toward most countries. When asked to rate their feelings toward a list of countries on a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 being very cold or unfavourable and 10 being very warm or favourable, more university-educated individuals ranked Asian countries such as India, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, and South Korea in the high (7-10) range. The exceptions to this are China and the United States. Almost an equal number of respondents from each group ranked the United States in the high range. The opinions of the different education groups converge when it comes to China – most respondents from each group ranked the country in the low or moderate range.

Q: Please rate your feelings towards some countries or regions.

Q: Please rate your feelings towards some countries or regions.

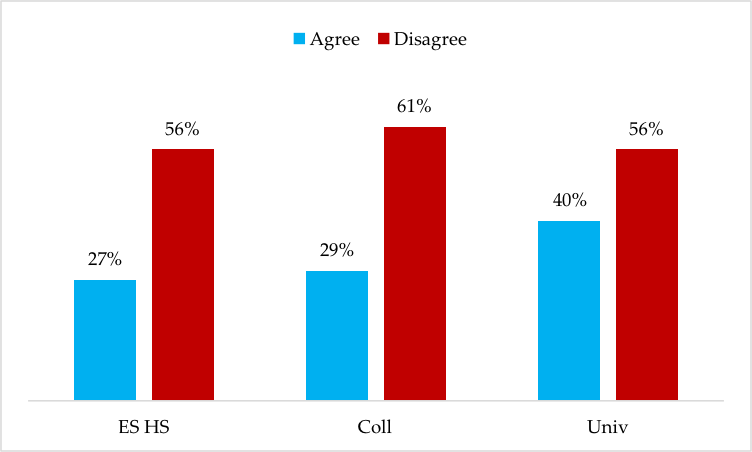

It is also interesting to note that compared with the other two categories, more university-educated individuals agree with the statement: “I consider Canada to be part of the Asia Pacific region.”

Q: Do you agree or disagree with the following statement: "I consider Canada to be part of the Asia Pacific region"?

Note: Respondents who answered “Don’t know” are not included.

Views on Engagement

Education is also positively linked to views on political and economic engagement with Asia. Although Canadians are largely open to engagement, those with a university education are more supportive of strengthening economic and political relations with Asia, and think that it should be Canada’s top foreign policy priority (50%). They also consider the growing importance of China (52%) and India (75%) as economic powers to be more of an opportunity than a threat. Compared with the other groups (60% for those with high school education or less, and 62% for those with some college education), those with university education (72%) are also more likely to believe that in dealing with the rise of China’s power, Canada should undertake friendly cooperation and engagement with the country. Compared with 43% of respondents each from the other groups, more university-educated individuals (52%) disagree that China’s growing economic presence in Canada is a direct threat to Canadian values and way of life.

The level of openness to engagement may be the result of the perceived influence of other economies on Canada’s prosperity. Canadians were asked to rate the importance of a list of countries to Canada’s prosperity on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 being not at all important and 7 being very important. Generally, those with a university education are more global in their outlook, and believe that Canada’s prosperity is connected to other countries. This observation is true for China, the European Union, India, Japan, South Korea, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and the United States, where higher education is linked to higher perceived importance of the respective country to Canada’s prosperity.

Education is also linked to openness in pursuing a closer economic relationship with China. More respondents with a college diploma (51%) or university degree (52%) agree that they could be persuaded to support a closer economic relationship with China if they knew more about what was involved, compared with those with high school education or less (44%). Those with higher education are also more positive about Asian investment in the country. They are more likely to support economic incentives from the government to encourage Canadian companies to set up operations in Asia, and initiatives to facilitate trade and investment missions for Canadian companies to visit Asian countries.

Canadians are generally supportive of Canada entering into free trade agreements with other countries and regions, but, here as well, those with university education are more supportive. When asked about individual countries and regions, university-educated individuals were also more supportive of FTAs with Australia, China, the European Union, India, Japan, and the ASEAN region. Similarly, when asked if entering into a free trade agreement with South Korea in 2014 was a good idea, 57% of those with a university degree agreed, compared with 45% of those with high school education or less, and 48% of those with some college education.

The attitudes flip when it comes to residential real estate investment from China. More university-educated (64%) and college-educated (63%) individuals believe that the government is allowing too much investment in this area, compared with 56% of those with a high school diploma or less. Canadians from all education groups are also concerned about increased competition, and believe that the low cost of labour in Asia makes it difficult for Canadians to compete.

When asked about the importance of Asia to their province’s prosperity, 67% of university-educated individuals feel that Asia is important, compared with 51% of those with a high school diploma or less, and 54% of those with some college education. More university-educated individuals also agree that the government should open provincial trade offices in Asia (65%), increase the number of student exchanges and university agreements between their province and Asia (75%), and place more emphasis on teaching about Asia in their province’s education system (65%) and on teaching Asian languages in their province’s schools (48%).

Views on Human Rights

Canadians overall are concerned about human rights; however, more education is linked to greater concern. Among university degree holders, 53% disagree with the statement that “we can’t afford to stop doing business with or in Asian countries just because of human rights concerns.” Also, 43% disagree that “the human rights situation in China today is better than it was 10 years ago,” compared with 34% of those with a high school diploma or less. Moreover, 63% of university-educated individuals agree that promoting democracy in Asia should be a major priority for the Government of Canada, compared with 50% of those with a high school diploma or less, and 56% of those with some college education. Also, 81% of university-educated individuals think that Canada should raise human rights issues in its relations with Asian countries, compared with 66% of those with a high school diploma or less, and 73% of those with some college education.

Policy Priorities

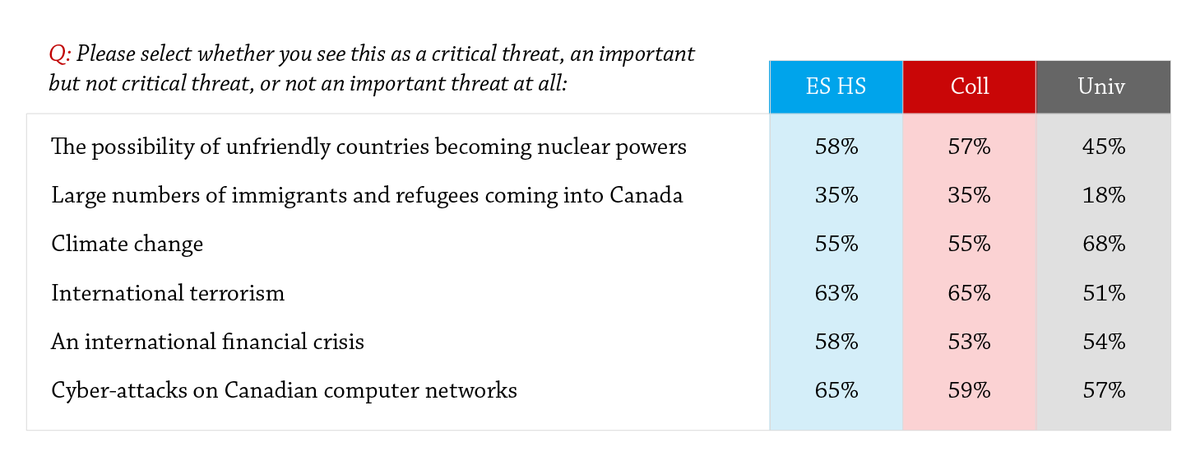

People with different education levels differ in their level of concern for various global issues. Compared with those with high school education or less and college-educated individuals, university degree holders are less concerned about the possibility of unfriendly countries becoming nuclear powers, large numbers of immigrants and refugees coming into Canada, international terrorism, and cyberattacks on Canadian computer networks. However, they are much more concerned about climate change. Further, Canadians from all education groups are concerned about an international financial crisis.

Note: Percentage indicates the number of respondents who see the option as a “critical threat.”

Note: Percentage indicates the number of respondents who see the option as a “critical threat.”

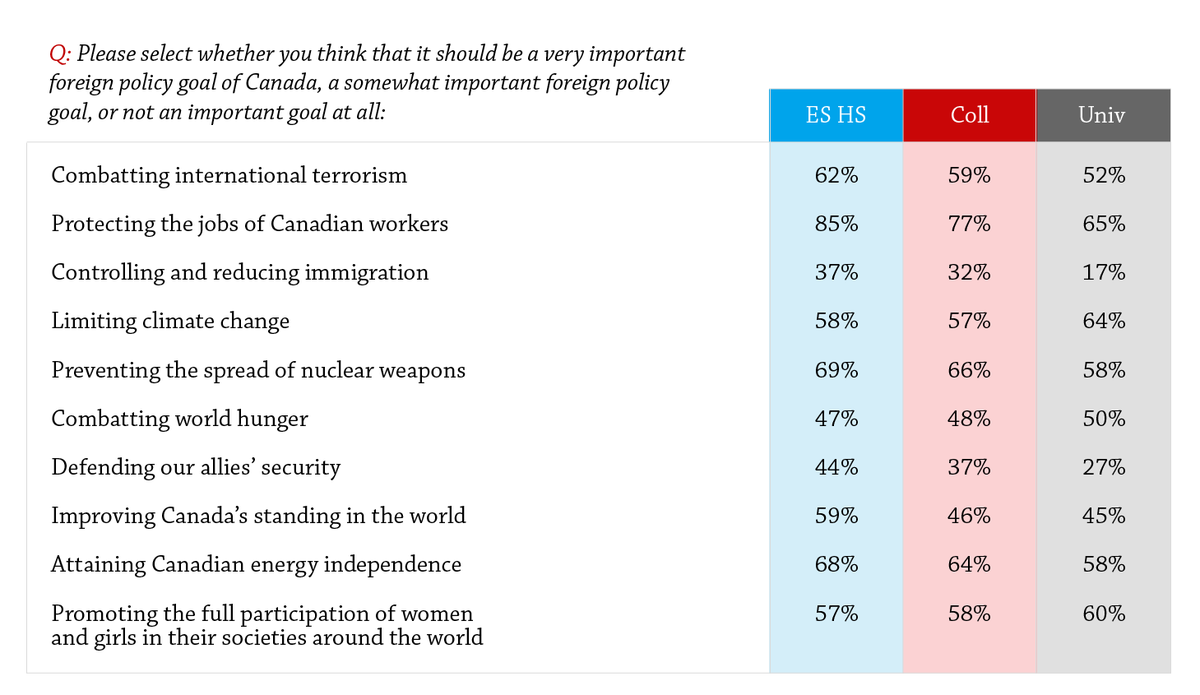

These perceived threats define their priorities as well. Respondents were asked to select how important various foreign policy goals should be for the Canadian government. Higher levels of education are linked to lower priorities for several goals, including combatting international terrorism, protecting the jobs of Canadian workers, controlling and reducing immigration, preventing the spread of nuclear weapons, defending our allies’ security, improving Canada’s standing in the world, and attaining Canadian energy independence. Although all Canadians think that limiting climate change should be a very important goal for the Canadian government, more university-educated individuals consider it critical. Canadians from all education groups are almost equally concerned about combatting world hunger, and promoting the full participation of women and girls in their societies around the world.

Note: Percentage indicates the number of respondents who see the option as a “very important” goal.

Note: Percentage indicates the number of respondents who see the option as a “very important” goal.

Summing Up

We see that education is positively linked to openness to trade and investment. However, interestingly, Canadians who are more educated have greater concerns about residential real estate investment from China, and believe that the government is allowing too much investment in this area. Canadians from all education groups are also concerned about increased competition from Asia due to the low cost of labour.

Education also positively affects feelings toward other countries. Interestingly, China is the exception, where the feelings of Canadians from all education groups converge.

Canadians who are more educated are less concerned about various international threats. However, climate change is the issue that university-educated individuals are more concerned about, and they consider limiting it as a very important policy goal for the Canadian government. For all Canadians, promoting the full participation of women and girls in their societies around the world is a very important foreign policy goal.