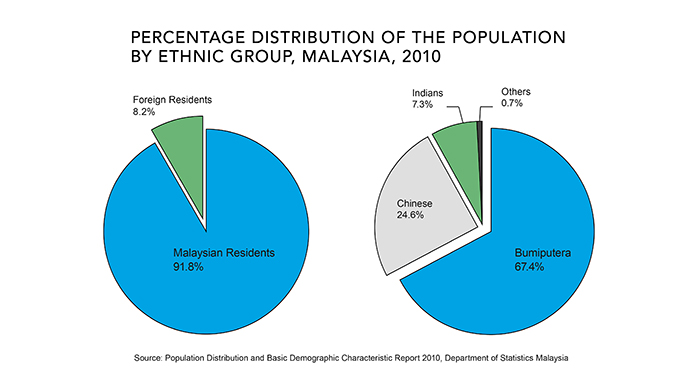

Malaysia’s demographic composition is fairly diverse. The 2010 census indicated that the country was comprised of over 50 ethnic groups, with 30 per cent being first or second generation immigrants. It is estimated that by 2031, 50 per cent of Malaysians over the age of 15 will be immigrants or have foreign-born parents. In addition to the indigenous Malay Bumiputera population, most of the population originates from India and China. After Singapore, Malaysia has the second largest share of foreign nationals in the labour force in Asia. Given this, Malaysia’s policies favour the accommodation of diversity and multiculturalism. Earlier this year, however, the government quickly retracted a recommendation that sought to recruit 1.5 million Bangladeshi workers to fill low-skilled jobs after a widespread public outcry. What does this tell us about the direction that Malaysian immigration policy is heading, and does it speak to already existing tensions around immigration?

The ‘Three Cultures’ Model

After gaining independence from Britain in 1957, Malaysia sought to establish a single, multicultural nation, but with a common identity. This was supposed to help the new state distinguish itself from the ‘three cultures’ model institutionalized by the British. Under this model colonial Malaysia’s population was categorized into three main groups: the indigenous Muslim Malays, the Hindu Indians, and the Chinese, who remained distinct and were administrated differently. However, these broad categories were not reflective of the many diverse languages, religions and cultures in the country. Post-independence initiatives to encourage multiculturalism included creating a shared education system, but with Malay as the common language. Additionally, all major religious holidays are nationally observed. Despite attempts to move beyond the three cultures model, elements of it were still evident in the early development of Malaysia’s immigration policy. For example, the first post-independent Immigration Act in 1959 restricted immigration to higher-skilled candidates. Ultimately, this initiative reduced the inflow of Chinese and Indian immigrants, largely classified as “low-skill” workers at that time.

In response to escalating tensions between the Chinese and Malay populations in the late 1960s, the government reprioritized its socio-economic policies under a New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP introduced a wide range of affirmative-action policies that aimed to reduce poverty and promote growth across races, but disproportionately benefitted the Malay Bumiputera population over others. The concessions made available to this population ranged from favourable electoral quotas, wider-ranging land rights, and other forms of government aid. This initiative did contribute to a massive decline in instances of absolute poverty – from 49 per cent of total households in 1970 to five per cent by 2002. However, these initiatives have drawn criticism for appealing to Malay nationalist sentiments without understanding the economic realities of various other cultural groups. For example, the Indian population on whole is poorer and less educated, and does not have access to these affirmative-action based initiatives.

In response to escalating tensions between the Chinese and Malay populations in the late 1960s, the government reprioritized its socio-economic policies under a New Economic Policy (NEP). The NEP introduced a wide range of affirmative-action policies that aimed to reduce poverty and promote growth across races, but disproportionately benefitted the Malay Bumiputera population over others. The concessions made available to this population ranged from favourable electoral quotas, wider-ranging land rights, and other forms of government aid. This initiative did contribute to a massive decline in instances of absolute poverty – from 49 per cent of total households in 1970 to five per cent by 2002. However, these initiatives have drawn criticism for appealing to Malay nationalist sentiments without understanding the economic realities of various other cultural groups. For example, the Indian population on whole is poorer and less educated, and does not have access to these affirmative-action based initiatives.

Refugees, ‘3D’ Jobs and Trends Moving Forward

Understanding the immediate post-colonial context sheds light on the challenges facing Malaysian immigration policy today. In 2015, Prime Minister Najib Razak announced that the country would be accepting 3,000 refugees from Syria. This is in accordance with Malaysia’s history of accepting refugees fleeing conflict, which includes a number of displaced Bosnian Muslims from the former Yugoslavia and 53,900 Rohingya refugees from Myanmar. However, Malaysia is not a signatory to the UN Convention on Refugees, and makes no distinction between undocumented refugees and workers classified as “illegal.” The Malaysian Strategic Research Institute states that this may contribute to a “two-tier” system where existing refugees and undocumented residents living for long periods in the country are overlooked.

Similar contradictions exist in debates surrounding temporary foreign workers. Despite worker shortages in labour intensive industries, resistance continues around the issue of foreign workers. At the moment, Malaysia has 2.1 million registered foreign workers — mainly from Indonesia, Vietnam, Nepal, Myanmar and Bangladesh — who work in positions commonly referred to as ‘3D’ jobs: dirty, dangerous and difficult. It is a commonly held perception that local, and especially young, Malaysians are unwilling to do these jobs. To fill these posts, the government proposed to recruit 1.5 million Bangladeshi workers in February 2016, but such was the public backlash that the government ultimately suspended all foreign worker recruitment programs, indefinitely. A 2012 International Labour Organization study measuring public attitudes on immigration showed that while 76 per cent of respondents recognized the need for migrant workers to fill certain jobs, 80 per cent of respondents felt that government policies to admit these workers should be more restrictive. The government is currently following World Bank recommendations to assess domestic labour market demands more rigorously before opening immigration programs again. However, anti-immigration stances are rooted in arguments that identify foreign workers as increasingly contributing to local crime.

Given these public debates, it will be interesting to see how Malaysia will apply goals of shared cultural prosperity from early iterations of the NEP to the current social context. While economic necessity may force the government to take a strong stance on immigration, work still needs to be done to protect diversity in the country.

To explore other posts in our Migration Matters series, please click on the links below.

Migration Matters: Project Overview

Migration Matters: Japan