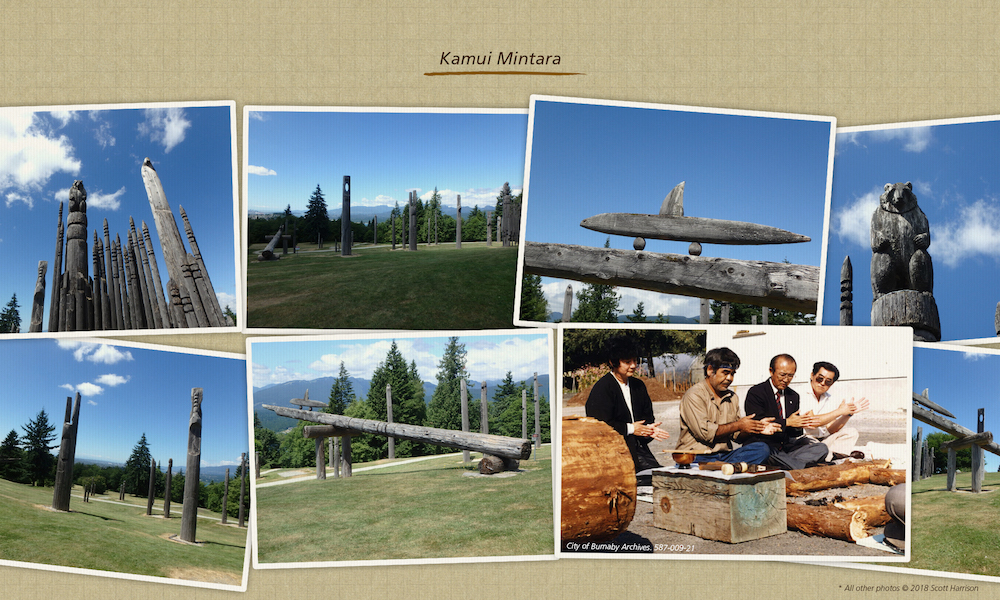

In May 1986, Indigenous Ainu master wood carver Toko Nupuri arrived in Vancouver on his way to Burnaby with his wife as part of a delegation from Kushiro, Hokkaido to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Kushiro-Burnaby sister city agreement. During a visit to Simon Fraser University, Toko parted from the delegation to walk the grounds.

At one point he found himself at the west end of Burnaby Mountain Park, which overlooks Vancouver with the Lion’s Gate Bridge in the distance. Inspired by the view, Toko proposed to Burnaby’s attending mayor that he create a sculpture to commemorate the good relations between the two cities. In February 1990, he returned with his son to start work on what would become “Kamui Mintara,” or Playground of the Gods.

Built to commemorate 25 years of friendship between the two cities, Kamui Mintara crosses Ainu mythology and art with the First Nations’ totems of British Columbia. The sculpture continues to stand today, attracting residents and visitors from around the world. In the summer of 2015 it was the site of 50th anniversary celebrations between the two cities, at which Burnaby Mayor Derek Corrigan officially renamed the area around the sculpture from Centennial Park to Kushiro Park. The sculpture and the relationship with Kushiro have since informed Burnaby’s other international twinning relationships.

This is but one small snapshot of an exchange born of Japan’s many city or prefecture twinning relationships with Canada and other countries around the world. A recent article in International Journal that broadly discusses Canadian provinces’ foreign policy in Asia suggests that twinning or so-called sister relationships between Canadian municipalities or provinces with counterparts in Asia is a key component of Canadian subnational diplomacy. Questions remain, however, as to the value of these initiatives for building trans-Pacific ties or for overall gains in provincial or national foreign policy. At a minimum, in the current environment of rising anti-globalism and xenophobia, twinning relationships provide the infrastructure for citizens to remain globally engaged. Japan’s international city and prefectural twinning relationships offer a window into how Japanese connect to the world and provide lessons for Canada.

Japan’s Twinning Agreements

While the idea and practice of sister cities dates from hundreds of years ago in Europe, modern sister city relationships in general originated with US President Eisenhower’s “People-to-People Program” aimed at countering Cold War tensions by promoting friendship and peace via exchanges. Japan’s first sister city relationship was signed on December 7, 1955 between Nagasaki and Saint Paul, Minnesota.

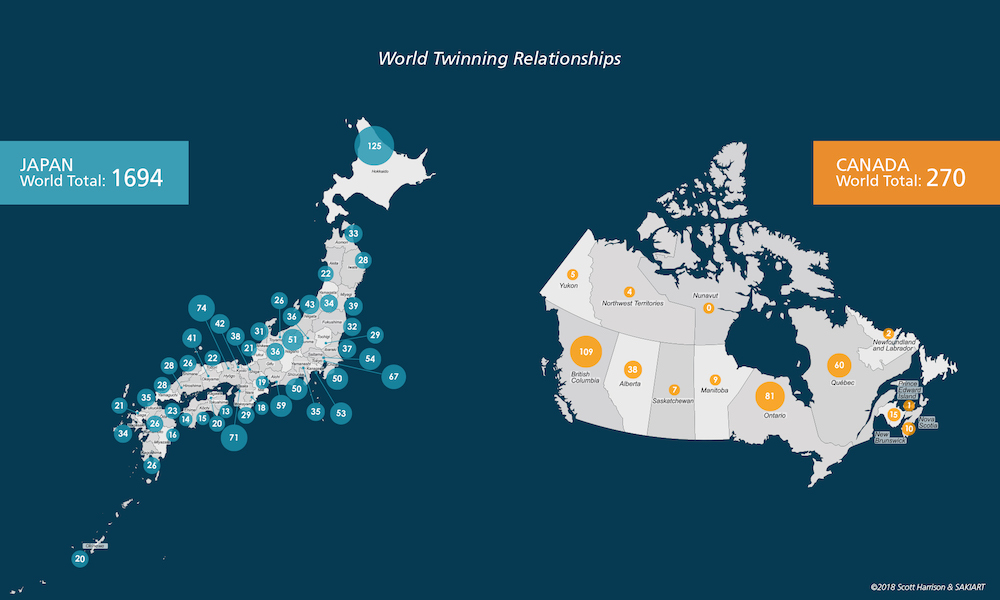

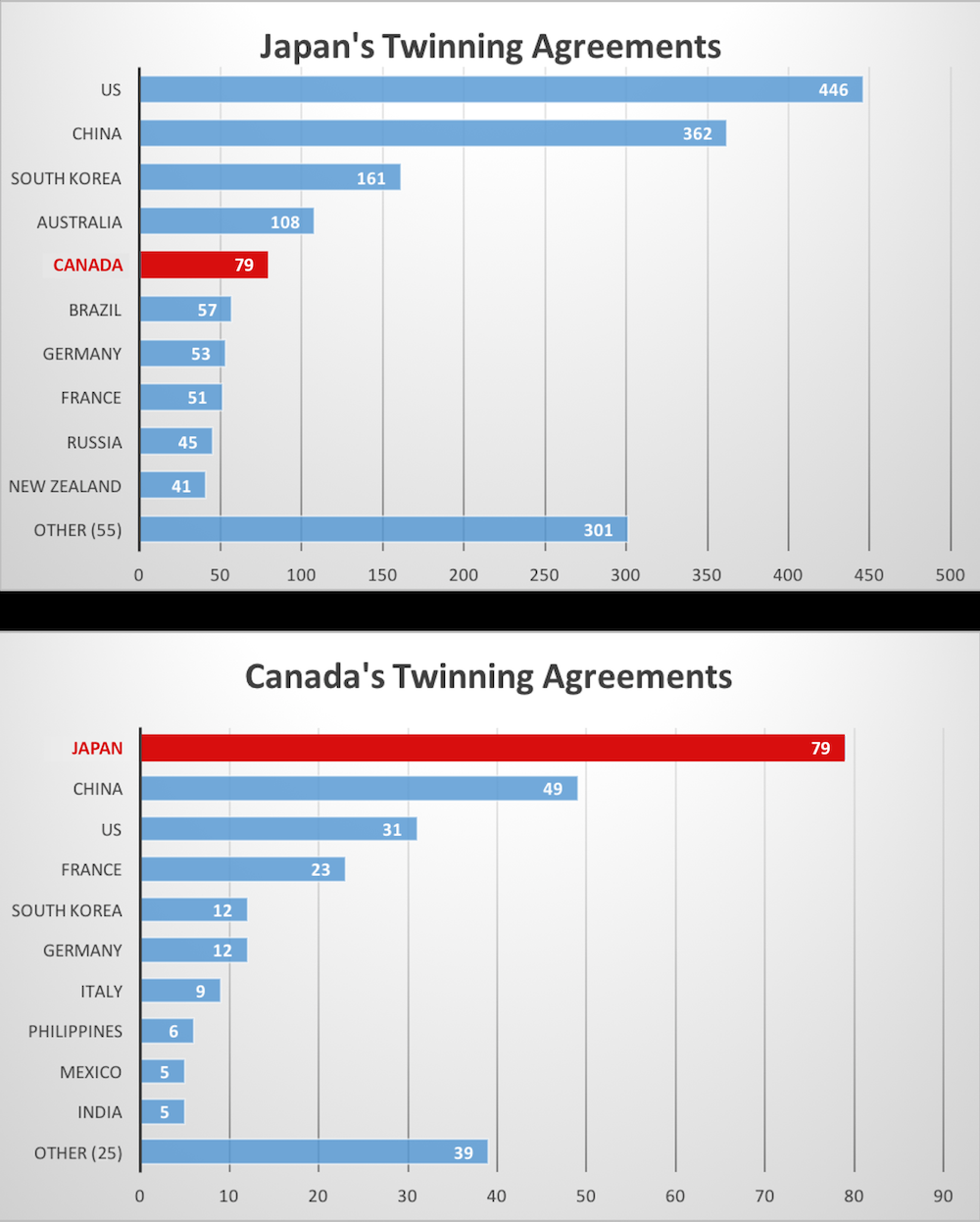

Since then Japanese municipalities and prefectures have signed almost 1,700 agreements (of these, 158 are prefecture-level agreements) with 65 different countries and territories.

Canadian municipalities and provinces/territories, on the other hand, are engaged in about 270 or so agreements (15 of these are provincial-level agreements) with 35 countries worldwide.

These numbers only include sister or twinning agreements and not several other types of similar agreements that range from municipal and national park partnerships, memoranda of understanding, and friendship agreements.

Twinning relationships have no universal definition, but they generally consist of four characteristics:

- They are signed by the heads (i.e. mayors, premiers, governors) of two jurisdictions and are meant to last indefinitely;

- They are not limited in scope or to a particular project, although most are centred around culture, education, and political exchanges;

- Neither side is meant to profit over the other; that is, they are based on genuine reciprocity; and,

- They are organized and run by unpaid volunteers and these people and their organizations are often grass-root based and don’t rely on the patronage or support of national governments.

With the exception of the last point, these apply to all of Japan’s agreements.

Japan-Canada Agreements

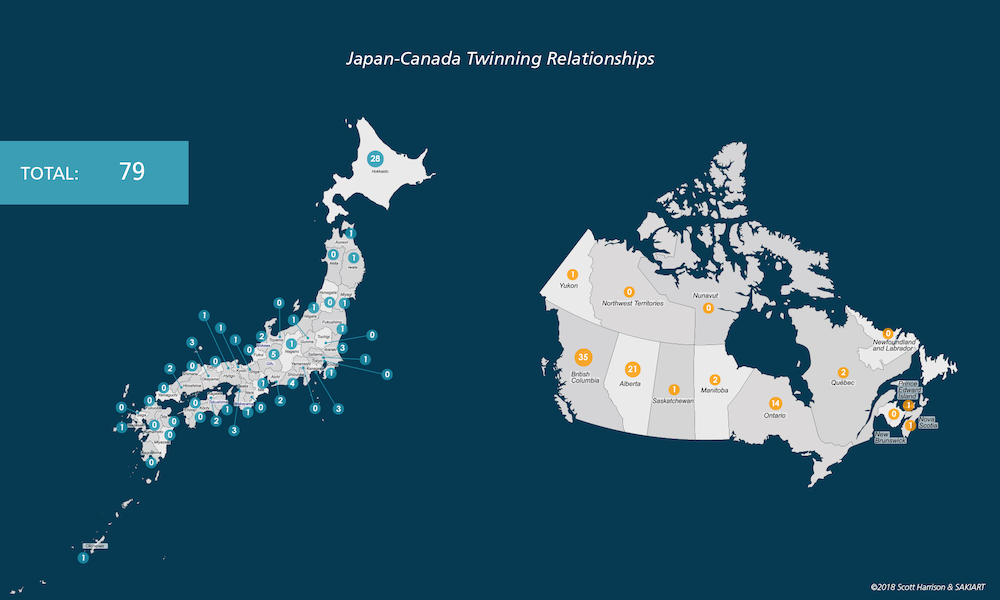

Most of Japan’s agreements are with the United States. Canada is Japan’s fifth largest partner for twinning agreements, representing about five per cent of Japan’s total agreements.

While Japan’s percentage of agreements with Canada is small, Canada’s percentage of agreements with Japan is quite high, at 29 per cent of world-wide agreements and over 50 per cent of those in the Asia Pacific. This has offered Japan the opportunity to have a rather high influence in Canada’s world of twinning, that is people-to-people exchanges, student exchanges, cultural activities, and to a lesser extent so far, business.

Japan’s oldest sister city relationship with Canada was signed on April 10, 1963 between Moriguchi, Osaka prefecture and New Westminster, British Columbia. A few other agreements were signed in the 1960s and 1970s but almost 70 per cent of Japan’s agreements around the world and with Canada were signed in the 1980s and 1990s, a period that coincided with a waning of the Cold War and when Japan had returned to world economic prominence after its three-decades-long run of strong economic growth.

In Japan, the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR) was established in 1988 to promote the country’s sister cities and other initiatives such as the JET Program (Japan Exchange and Teaching Program) that work to support Japan’s internationalization. CLAIR maintains 67 offices throughout the country as well as seven overseas offices (New York, London, Paris, Singapore, Seoul, Beijing, and Sydney). They perform an annual survey that helps them understand these relationships, but their involvement is more like a catalyst than an archival depository of each sister relationship; that kind of information is usually held by each individual municipality or prefecture.

Canada does not have anything quite like CLAIR. In 2011, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Development (now Global Affairs Canada) tried to set up a registry and website through the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. This was spurred by foreign and Canadian ambassadors who saw potential for linkages beyond political and cultural ties, most notably economic development. In the end it didn’t come to fruition.

Global Affairs Canada has kept its interest in these issues by aiding and promoting twinned jurisdictions as a means to strengthen bilateral and people-to-people ties but its work is limited partially because provincial- and municipal-level issues fall outside its mandate and because of a lack of funding. There are numerous municipal-level organizations and a few provincial-level organizations that work with twinning issues, but they are usually limited by their specific city, program, or a target country. In short, knowledge keepers are diverse and spread out; some are/were city or provincial officers, others are community members. While documentation is split between personal files and those buried in archives, many of the stories behind these relationships remains oral history. In short, there is no central information source that can be used to paint a picture about twinning relationships in Canada.

Looking to Japan can help provide a better sense of Canada’s twinning relationships. For example, in 2006 CLAIR reported that education, culture, sports, and government administrative exchanges account for over three quarters of Japan’s exchange content. But the breakdown diversifies when separated between countries and regions. For example, education exchanges make up about half of exchanges with North America and Australia followed by administration (14%), culture (12%), sports (3%), and business (2%).

That business exchanges rank so low is noteworthy since one of the key justifications for creating twinning agreements regardless of jurisdiction is that they will help foster economic development between two jurisdictions through trade, investment, and tourism. As business exchanges take up a small portion of overall twinning content and that explicitly connecting economic development directly to twinning is a challenge many twinning relationships in Canada have come under public scrutiny. The main argument against twinning in Canada is that the expenses incurred to maintain these agreements are not worth it as they benefit only a handful of politicians and are elitist. The money, goes the argument, could be better spent on local initiatives and programming.

Many of the Canada-Japan twinning relationships, as with Canadian twinning relationships in general, have become defunct, while others are under continual pressure to justify their activities and secure public support. In Japan, there is a national level organization (CLAIR) that helps keep these agreements active, promotes new ones, and works to revitalize those that are in danger of failing. In Canada, we rely on the keenness of mayors and their offices and a wide variety of twinning associations that are often run by a handful of volunteers.

Twinning Activities and Outcomes

Japan has used twinning relationships as one means for promoting the internationalization of its citizens and expanding its presence internationally. Looking at a few concrete examples from Japan-Canada twinning agreements shows how this has played out.[1]

Indigenous Exchanges

In addition to the Kushiro-Burnaby relationship, a number of other Japan-Canada twinned jurisdictions have also facilitated Indigenous exchanges.

For example, in 1985 representatives from the Ainu Cultural Centre and Don Assu from the Nyuyumbalees Society, and the Band Manager for the Cape Mudge First Nation, signed a Treaty of Peace and Alliance at the Kwagiuth Museum as part of the Ishikari-Campbell River sister city relationship. This exchange was reciprocated in 1986, when a few individuals from Cape Mudge First Nation travelled to Hokkaido.

Abashiri and Port Alberni signed a sister agreement in 1984. Four years later Port Alberni gifted a totem pole to Abashiri, which stood at Abashiri Central Park until 2000 when it was moved to Okhotsk Cultural Exchange Center, also known as Echo Center 2000, a complex built to promote arts and culture.

In the case of the Hokkaido-Alberta sister relationship, in 2002 two researchers from the Historical Museum of Hokkaido (now Hokkaido Museum) spent six weeks at the Provincial Museum of Alberta (PMA) (now Royal Alberta Museum). This was followed by two individuals from the PMA going to Hokkaido. These research exchanges focused on Indigenous-newcomer cultural interactions. There have been similar exchanges since. Many of these kinds of Indigenous exchanges and networking at the international institutional level fall off the radar even among the small number of scholars that focus on Indigenous internationalism.

Education

The Hokkaido-Alberta twinning relationship provides a few interesting examples of expanding knowledge of Japan in Canada. For example, this relationship has helped establish strong education and language links between the two jurisdictions. Martha Rogalsky, Senior Trade and Investment Officer with the Government of Alberta, says that it provides opportunities for Alberta Kindergarten to Grade 12 students and teachers “to develop Japanese language skills, strengthen intercultural knowledge, and become more familiar with contemporary Japan through a variety of long-standing programs.”

Roy Kariatsumari, President, Rocky/Kamikawa Friendship Society and Vice-President, Alberta-Japan Twinned Municipalities Association, provides a concrete example of what this means on the ground. In 1988, Kamikawa, together with its sister city of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, initiated the first Japanese language program in the province. In 1994, Hokkaido, in co-operation with Alberta and Rocky Mountain House, sent two Japanese language teachers to work in Alberta for 18 months. Rocky Mountain House received similar teachers from Hokkaido from 1994 to 2006.

This was part of the Regional and Educational Exchanges for Mutual Understanding (REX) program, administered by the Government of Hokkaido (in partnership with the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (MEXT) in co-operation with prefectural governments since 1990). This program has provided Alberta with two Japanese language teachers to assist schools with the development of their Japanese language programs. Alberta has benefited from this program for about 25 years.

The Alberta-Hokkaido student exchange program permits eight to 10 Hokkaido high-school students to participate in an annual four-month exchange with their Alberta counterparts. In addition, Rogalsky adds, 12 Hokkaido schools are also twinned with schools in Alberta.

Within these initiatives, Kariatsumari explains, Alberta created high-school Japanese language curricula for Japanese 15, 25, 35 and later Japanese 10, 20, 30 matriculation program (for Grades 10, 11, 12) that can be used as part of Canadian university entrance scores. The Hokkaido-Alberta twinning agreement, which was signed in 1980, was essential for supporting this kind of Asia-related competency and skills for Canadian youth.

Business and Trade

Directly attributing specific deals and dollar amounts or jobs to a Japan-Canada twinning agreement is generally no easy task. For starters, there are few news releases announcing such items as we might see from federal or provincial Canadian trade missions – even if certain missions are directly connected to a twinning agreement. Second, as with other areas of twinning, information is decentralized with a diverse set of knowledge holders. Part of the reason for this is that it is difficult to track how long-term, slow-moving business relationships mature. There are cases in which international students, either from Japan to Canada or visa versa, contributed to international trade within twinned jurisdictions as long as 20 years after their exchange.

That businesses and trade within twinning agreements appears less documented than cultural and education exchanges is ironic because financial numbers are often at the forefront of concerns when planning or initiating new twinning relationships – and an area that receives the most critical commentary on the value of twinning relationships. Here we should be mindful that business usually follows relationship building, especially in Asia, and not the other way around.

Ways Forward

So what does all this mean for Canada?

To start, looking at the total number of Japan’s twinning relationships and how Canada fits into the mix shows that Japan is more important for Canada than Canada is for Japan. Also, since information on twinning relationships is scattered it is difficult to fully understand how Canada-Japan twinning agreements (or twinning in general) contribute to deepening relationships between two jurisdictions, especially in the area of business and trade. This means that policy recommendations surrounding twinning are likely based more on anecdotes and politics than evidence-based analysis.

Japan offers a number of lessons for how Canada at the federal, provincial and municipal levels on how to proceed to better understand and make use of its twinning agreements. For example, Japan has been holding Japan-China-South Korea Trilateral Local Government Exchange Conferences since 1999 and Japan-France Local Government Exchange Conferences every other year since October 2008 as mechanisms to strengthen co-operation and exchange between local governments.

Perhaps there is a possibility for Canada to do something similar with Japan. The focus of these conferences could be on any one of the pressing issues that face Japan and which Canada should be paying attention to for its own future, including education, international internships, the health-care economy, energy security and the environment, disaster preparedness and recovery, immigration, or the deepening urban-rural divide. Having people engaged at local or provincial levels on such complex issues may help bring these seemingly abstract issues to life.

CLAIR also offers lessons for Canada and the provinces to evaluate the benefits and risks of establishing a national or subnational organization dedicated to fostering twinning relationships. While critics may disregard twinning as an outdated model of engagement and thus a fruitless pursuit, we should not be so quick to dismiss the role of these relationships. There are two main reasons for this. First, we know too little about these relationships to make any strong evidence-based critique of their long-term impact. A Canadian equivalent to CLAIR could help sort this out. Second, we should consider that twinning relationships are far from an outdated concept in Asia. Japan continues to see merit in CLAIR as evidenced by its ongoing activities and China, the world’s second largest economy and Canada’s second largest trade partner and main source of tourists from Asia, has been actively maintaining and increasing the number of its twinning relationships around the world, including with Canadian jurisdictions.

But perhaps the most important reason for more closely following Japanese twinning relationships is that they provide valuable lessons on how Canada might increase its presence around the world, especially in the Asia Pacific. Canada should utilize twinning agreements to remind Japan, and ourselves, that our country, provinces, and people are investing in what it takes to be engaged and present at multiple levels in the most dynamic region of the world. While high-level trade agreements provide important framework for engagement it is individual people and the institutions in which they work that are the drivers of Canada’s relationship with Japan.

[1] Sports exchanges is another notable area of Japan-Canada twinning. For example, the Alberta-Hokkaido twinning agreement has helped develop strong ties within the world of curling.