On November 15, the world’s population officially hit eight billion. In the lead-up to this historic day, the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) attempted to dissipate fears of overpopulation in an increasingly unequal world – and warned against the imposition of population controls. For decades, such fears have gripped China’s top policy-makers, who have employed harsh tactics to curb population growth. However, Beijing is now fretting over the opposite problem: an imminent demographic crisis over faltering population growth.

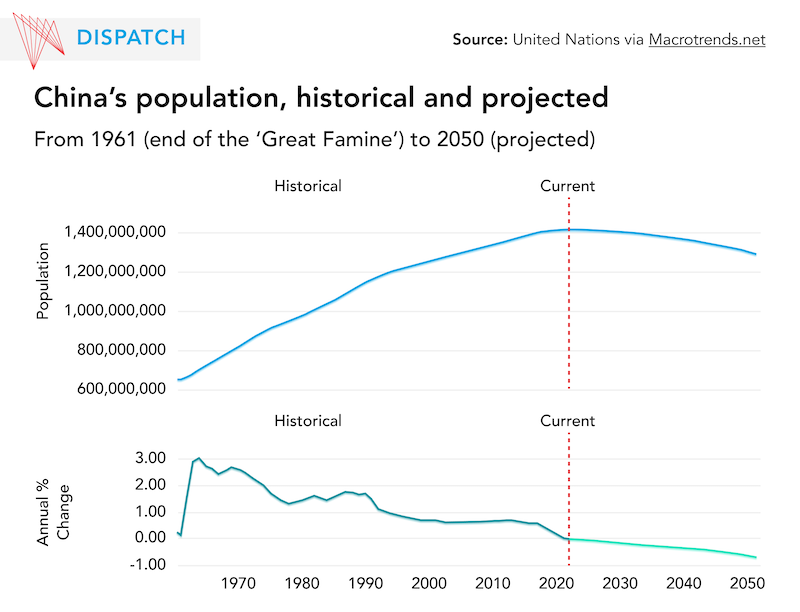

Despite moving away from a one-child policy to two- and three-child policies in 2016 and 2021, respectively, China’s birthrate fell for five consecutive years to a record low in 2021, while the country’s fertility rate dropped to 1.16 children per woman – well below the rate of generational replacement (2.1) and among the world’s lowest birthrates. With new births expected to sink below 10 million by the end of 2022, China’s population is set to shrink for the first time since the Great Famine of 1959-61. A shrinking population strains the country’s capacity to care for its rapidly increasing elderly population.

Such a drastic demographic change came as a surprise: as recently as 2019, experts still expected the Chinese population to grow until 2029. A sense of urgency imbued the central government’s announcement, in August 2022, of a countrywide pronatalist plan, the ‘Guidelines for Further Improving and Implementing Fertility Support Measures.’ As Beijing’s most comprehensive pro-birth plan to date, the guidelines include a point nudging local governments to gradually include assisted reproductive technology (ART) services in public health insurance coverage.

This is the first time a Chinese national policy document considers ART services as part of the national health insurance system, indicating the government’s intention to make infertility treatments more accessible. For years, women in China have struggled to access ART due to legal, financial, and structural barriers. This new guideline has ignited hopes that China will eventually knock down some of the technical barriers to ART services access in the face of the demographic crisis.

According to the National Health Commission (NHC), China’s top public health policy-making body, ART includes two main types of techniques: artificial insemination (AI), and in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-EF) whereby an egg is fertilized by sperm outside a woman’s body (and its derivative techniques).

At face value, ART could boost China’s declining birthrate, in part because of the growing challenge of infertility. A 2021 study published in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, shows that China’s infertility rate rose from 12 per cent in 2007 to 18 per cent in 2020. This means that one in 5.6 Chinese couples of childbearing age faces challenges in conceiving a baby. Doctors believe delayed childrearing is a major contributing factor: in 1990, the average age of first-time mothers was 24.1; by 2015, that figure had risen to 26.3. Besides age-related infertility, fertility is also affected by stress, unhealthy lifestyle choices like smoking and lack of sleep, environment pollution, and other factors accompanying rapid economic development and cut-throat market competition.

The sizable population in China with infertility problems represents an astronomical potential market value for ART-related industries – a 2020 estimate by Beijing-based securities broker Dongxing Securities put it at C$427 billion (2.24 trillion yuan). Yet in 2018, only 1.2 per cent of infertile couples in China received ART services. In comparison, in developed countries, some 40 to 50 per cent of infertile couples opt for ART services. This huge discrepancy reflects the hurdles in accessing ART services in China.

China’s regulatory regime around ART is highly restrictive as it only allows access for married, heterosexual couples with infertility diseases. Replying to a 2021 proposal to grant single women ART access, the NHC defended its position that egg freezing services should remain inaccessible to single women. The response cited potential health risks, unresolved controversies over delaying childbirth via egg freezing, and an ethical principle of anti-commercialization of ART.

This argument received widespread criticism and questioning online, as many spotted a dismissive attitude towards women and their ability to make informed reproductive choices for themselves. Others pointed to the NHC’s self-contradictory practice of permitting single men to freeze sperm for non-medical reasons.

Unbearable financial costs put ART services out of reach for many Chinese. Notwithstanding Beijing’s recent guideline, local authorities still have a long way to go in incorporating ART services into public health insurance. As such, many Chinese couples simply cannot afford spending an average of C$5,600 (30,000 yuan) per cycle to achieve pregnancy. Compounded by misguided perceptions of infertility treatment, ART services become a privilege enjoyed by the wealthy and well-advised.

The uneven distribution and quality of ART service providers also exacerbates the problem. In 2001, the NHC adopted the ‘Measures on the Administration of ART,’ establishing standards of ART service provision and a licensing regime. This has since led to a rapid growth of ART service providers. By 2019, 517 assisted reproductive clinics and 27 sperm banks have sprung up in China.

These ART service providers, however, are mostly located at large public hospitals in more developed cities, further reflecting the broader imbalance of medical resources in China. In 2020, public health experts from the NHC and China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention published the first-ever comprehensive analysis of ART activities in China. The study shows that in 2016, a total of 906,840 ART cycles – the highest figure in any country for that year – were performed. The majority were done in north China’s Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei; east China’s Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, and Shandong; south China’s Guangdong and Hainan; and Liaoning.

Additionally, the quality of ART service provision varies greatly from clinic to clinic. Many small assisted-reproductive centres in China can only perform dozens of cycles annually, and often fail to deliver successful results. The low success rates reflect a lower quality of service offered at these clinics, which in part is a result of lax state supervision and evaluation, as very few clinics lose their licences despite review processes in place.

Broadening ART access may well be a drop in the bucket in terms of boosting new births in China. In fact, once population decline begins, it is extremely difficult to reverse. However, removing these financial, structural, and legal barriers would mark a meaningful step towards upholding Chinese women’s reproductive rights.

As humankind reaches eight billion, UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem warned against population alarmism, arguing that the world is “still reckoning with the lasting impact of policies intended to reverse, or in some cases to accelerate, population growth.” In this spirit, China’s demographic crisis demands a stronger (and more humane) policy response to the arguably man-made consequences of a shrinking and aging population.