In June 2020, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore struck up the Digital Economic Partnership Agreement (DEPA), a ground-breaking, digitally-focused trade agreement. Since then, many economies have expressed interest in joining this novel pact. On October 5, 2021, South Korea signed documents to formally request to join the Agreement. South Korea’s request presents an opportunity to explore the world’s first digital-only trade agreement and its potential impact on Canada.

In December 2020, Canada notified the DEPA parties of its interest in joining the Agreement. In February of this year, Canada officially began exploratory discussions with those parties. One month later, Canada began public consultations with individuals and stakeholders on the current DEPA text and how DEPA could potentially be updated. The consultations closed in May, but Canada's exploratory discussions with DEPA members are ongoing.

Joining DEPA could have significant impacts for Canadian exporters as the digital economy becomes more and more important for businesses – in 2020, retail e-commerce sales in Canada increased by 70.5 per cent compared to 2019.

What is DEPA?

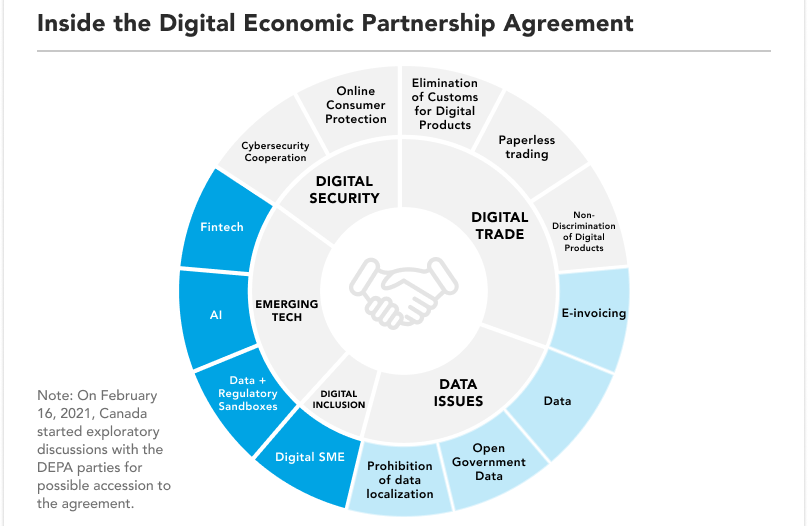

DEPA is a new international trade partnership agreement seeking to foster digital trade by regulating issues related to the digital economy, including digital inclusion, data flows and protection, and artificial intelligence.

It was created as a “live” agreement, meaning it can continuously be updated and modernized as needed. Current DEPA signatories – Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore – already enjoy market access to one another’s economies through their membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership (CPTPP). In a way, DEPA can be thought of as a side agreement to CPTPP that builds on its e-commerce chapter while also venturing into uncharted territories like e-payments, e-invoicing, and emerging technologies like AI and fintech. Intended to create international standards for the rapidly evolving digital economy and facilitate digital trade between signatories, DEPA has the potential to set the course for economies around the world.

The renewed interest in DEPA provided by South Korea’s formal application comes at an opportune time. The growth of the digital economy is in an exponential phase, and governments worldwide are scrambling to keep up and meet the data governance challenges posed.

The growth of the digital economy

The digital economy, or economic activity conducted through the internet and other forms of digital technologies, has radically transformed how goods and services are produced, sold, and consumed. The pace of transformation is only accelerating, facilitated by a shift away from hardware and towards software and data analysis. Today, the digital economy is estimated to account for as much as 15.5 per cent of global GDP, or $C14.35 trillion.

In Canada, digital economic activities have grown exponentially over the past decade to reach upwards of an estimated 5.5 per cent of national GDP. Canada’s digital economy has been expanding much faster than the overall economy, is increasingly impacting workers in non-tech sectors, and, according to an experimental study by Statistics Canada, the estimated value of Canadian data represents two-thirds of the current value of Canada's oil reserves. With data increasingly surpassing oil as the leading driver of wealth creation, and with the COVID-19 pandemic having accelerated the digitalization of services delivery, all companies are bound to “go digital.”

The current pace of technological development underpinning the digital economy is unlike anything we’ve seen since the Industrial Revolution, and the data governance challenges posed are complex and vast. Governments are playing catch-up, and pressing regulatory questions remain on issues such as data flows, data interoperability, and emerging technologies.

Going where no FTA has gone before

While it is not the first Agreement to set digital rules, DEPA remains a first-of-its-kind agreement. In contrast, the CPTPP contains an e-commerce chapter of its own, but it primarily deals with “old school” digital topics like trade facilitation through paperless trading and online consumer protection; elements that make the existing trade system more compatible with the digital age but that don’t reach into discussion and adaptation around next-frontier technologies.

For its part, DEPA also touches on “old school” digital components. Paperless trading is established in Module 2, and consumer protections against things like unsolicited commercial messages and online fraud are found in Module 6.

The Agreement also includes two e-commerce areas not covered by the CPTPP: e-invoicing and e-payments, also established in Module 2. Without reaching as far as to prescribe regulations for its signatories, DEPA recognizes the growing importance of these elements of the global economy and establishes interoperable standards through collaboration, drawing on a common set of e-commerce principles.

The Agreement also establishes rules of non-discrimination for digital products in Module 3, which means that no party to the Agreement can give favourable treatment to any digital products from one party over another. This applies mainly to a new wave of digital products defined in the Agreement as “computer programme, text, video, image, sound recording or other product that is digitally encoded, produced for commercial sale or distribution, and that can be transmitted electronically,” with a big exception for the broadcasting industry – not entirely surprising given the historical protection of cultural industries.

Module 4 on data issues builds on the commitments of the CPTPP, which prohibits data localization (i.e. restricting the collection, processing, and/or storage of data within a country) requirements to ensure free data flows. These flows are particularly important for AI companies. They help facilitate data innovation writ large, which is a recurrent aspiration of the Agreement.

Where DEPA really ventures into the future is in Module 8 on emerging trends and technologies and in Module 9 on innovation and the digital economy. While these sections don’t contain any rigid regulatory prescriptions, they create important and discussions and points of collaboration in emerging areas where there is such a need.

Module 8 includes an article on fintech cooperation, where the signatories not only set out standards but commit to actively “promote development of fintech solutions” and “promote cooperation between firms” in the sector, including with startups. And an article on artificial intelligence calls on signatories to promote the adoption of AI governance frameworks to facilitate the ethical adoption of AI technologies. And finally, in Module 9, there is a commitment to data innovation through open government data and even data and regulatory sandboxes (something not usually discussed nor endorsed by FTAs). This commitment to actively innovate at the next frontiers of technology and to allow for updates and modernization as its membership grows is what makes DEPA a living agreement.

Striking the right balance

While some may criticize the Agreement for either being too flexible or not showing enough teeth, the balance between the two meets the data governance challenges posed by the digital economy. Governments need to strike the right balance between, on the one hand, capturing the immense economic value of data, which a light regulatory touch may better facilitate, and on the other, safeguarding national security and the data privacy rights of citizens.

For example, Module 4 on data issues stipulates that “each party shall adopt or maintain a legal framework that provides for the protection of the personal information of the users of electronic commerce and digital trade.” This article is followed by the caveat that each party may take different “legal approaches” to protecting personal information and outlines a set of guiding principles for promoting the interoperability of standards.

Regardless of its exact implementation strategy, DEPA provides space for a much-needed discussion on emerging digital policy areas. Discussion on e-commerce surrounding the CPTPP and at the WTO has made some fledgling attempts to address digital trade issues but have largely been insufficient. Indeed, greater international collaboration is needed to facilitate digital trade and create international standards for the digital economy.

Built to spread

The key to DEPA lies not just with the parties to the Agreement but with its potential to expand. While new countries can accede to the Agreement, each module of DEPA can easily be slotted into other trade agreements. Countries doing business with the signatories may also face incentives to align their domestic policies with DEPA.

In DEPA’s Article 2.7 on e-payments, the parties agree to foster “the adoption and use of internationally accepted standards, promoting interoperability and the interlinking of payment infrastructures, and encouraging useful innovation and competition in the payments ecosystem.” These standard-setting and innovative aspirations speak to the spirit of the Agreement, and at the same time, reflect an ongoing challenge globally: hitting the right balance between regulation and innovation.

As the global digital transformation roars full speed ahead, many leading countries are going it alone. At the same time, the EU, U.S., and China have disproportionate power to unilaterally set the standards that will govern the future of the digital realm. But South Korea’s formal request to join DEPA means the Agreement is gaining members and traction. After all, there is strength in numbers, and DEPA represents a forum for smaller economies, like Canada and South Korea, to figure out what works in the digital economy and to be a part of the international conversation.