On May 9, voters in the Philippines will have their say in choosing who will lead the country for the next six years. There is a lot at stake – for the fate of the War on Drugs, the country’s foreign policy, its social media and information ecosystem, the role of authoritarian nostalgia, and overseas workers and those who depend on them.

The upcoming election will also tell us whether the country’s voters – especially younger Filipinos – will return the powerful Marcos family dynasty to the highest office. We share our insights and analyses on these issues through this six-part Dispatch series.

In this first Dispatch, we provide a quick primer on Philippines politics and elections, including an introduction to the leading candidates, some persistent features of who runs and how they campaign, and what the word “Trapo” tells us about the conflicting feelings many Filipinos have in choosing their leaders.

Filipino Politics: The Basics

The most powerful political positions that will be decided in the upcoming election are president, vice-president, and the 24-member Senate. From 1946 until the declaration of martial law under Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in 1972, presidents were limited to serving no more than eight consecutive years (two four-year terms). After Marcos’s ouster in 1986 and the drafting of a new Constitution in 1987, term limits were introduced for all elected officials, and presidents were limited to a single six-year term. If a president left office before the end of his or her term, their mid-term replacements were ineligible for re-election.

For the presidency, the qualifications for candidacy are quite broad. They include being at least 40 years of age on the day of the election and a natural-born citizen of the Philippines. Having a criminal record, however, is not a disqualifier. For example, Joseph Estrada served as president from 1998 to 2001 before being impeached on corruption charges. Despite being subsequently convicted of plunder, he ran (unsuccessfully) for re-election to the presidency in 2010.

Also, presidential elections in the Philippines are genuinely competitive and are typically contests amongst several candidates. The winning candidate does not need to reach a minimum threshold of votes – they merely need to get more votes than the other candidates to be declared the winner. Because of the number of candidates, it is not uncommon for the winner to come up short of a majority: in 2010, Benigno Aquino won with 42 per cent, and in 2016, Duterte won with only 39 per cent.

Although the electoral system in the Philippines was inherited from the U.S., a curiosity is that the vice-president is voted for separately from the president. This means that the president and vice-president can have different platforms and even have a confrontational relationship with one another. On the one hand, this arrangement could help to foster checks and balances between the two. On the other hand, it can contribute to a lack of coherence and organizational capacity, while also producing conflicting policy interests. For example, Duterte has repeatedly attacked his Vice-President, Leni Robredo, in public, while Robredo, for her part, has actively criticized the president’s stance on the War on Drugs and his COVID-19 policies.

Half of the Senate’s 24 members will also be chosen on May 9 (the other 12 seats will be contested in the next by-election in 2025). Senators in the Philippines are subject to a national vote rather than sub-national districts, which tends to make the Senate a kind of ‘training ground’ for future presidential candidates.

Meet the Candidates

The Front Runners

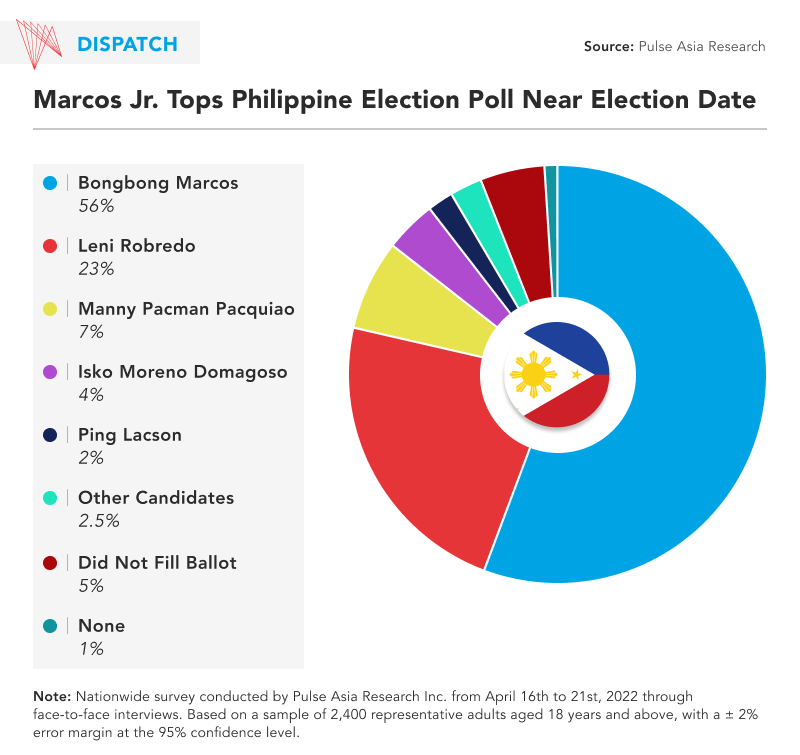

Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. has consistently led the pack in pre-election polling, with recent estimates showing the support of 56 per cent of the electorate. He is the son and namesake of the country’s long-serving dictator, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., whose rule (1965-1986) ended when the pro-democracy People Power Revolution of 1986 sent him and his family into exile in the U.S.

Marcos’s pledges to revive the economy have made him very popular with voters. Regarding COVID-19, he emphasizes the importance of vaccinations and their effectiveness in helping to get the economy back on track. When it comes to natural hazards, which are a fairly regular and destructive occurrence in the Philippines, Marcos stresses the need for the national government to be proactive in creating more evacuation centres. He also promotes reforestation on a “massive scale,” which could help alleviate the country’s air pollution problem and combat global warming. Moreover, he promises to pursue Duterte’s War on Drugs with the “same vigour,” but focusing more on prevention, education, and rehabilitation. To fund his campaign, Marcos Jr. receives massive support from wealthy friends and families and from eight political parties.

Running a distant second, currently at 24 per cent, is Vice-President Leni Robredo. Her platforms highlight transparency and accountability. She says she intends to regain the Filipino people's trust in the government by removing the “palakasan” (cronyism/nepotism) system, ensuring a reliable government, and levelling the playing field in the marketplace. Her office received the top audit grade from the Commission on Audit for three years in a row (2018-2020), helping to bolster her claims that she walks the talk on good government. Additionally, Robredo aims to support small businesses and unemployed individuals with initiatives such as a new Government Employment Program and unemployment insurance. Economically, she would focus on marine, manufacturing, and tech industries, with a goal to match Philippine skills with high pay and eliminate red tape through modernization and digitization. She would also promote climate-related industries, such as e-transport and climate-smart agriculture. Unlike her contenders, Robredo is not running on a party ticket, but rather as an independent candidate. She relies predominantly on her team of volunteers and those who devote time and money to support her campaign.

Campaign season is usually a festive affair in the Philippines, with colourful posters, splashy motorcades, and energetic rallies. These events and materials have been a significant means through which members of the public come to know about the candidates, and ‘face time’ can be more influential than campaign platforms in how voters ultimately decide.

But there are also some less savoury aspects of Philippines’ elections. For example, vote-buying was, for many election cycles, something that was carried out more often in poorer areas of the country, with campaign workers distributing cash in exchange for votes. It is believed that the practice has subsided, but in some cases, it has taken on somewhat of a veneer of respectability under the name “ayuda,” or “assistance,” in the form of gifts of money, clothes, food, or other items. In essence, though, this is still vote-buying that appeals to a Filipino cultural trait of “utang na loob,” or “debt of gratitude,” which is often taken advantage of by the wealthier and more powerful classes, including those in the political class.

A Star-Studded Affair

This year’s presidential and vice-presidential contests also reflect two other features of Filipino politics: celebrity and political dynasties. Celebrities figure into elections both as sought-after endorsers of candidates and as candidates themselves. In fact, the two candidates currently running third and fourth in the polling are both celebrities-turned-politicians.

Isko Moreno, the mayor of Manila, first made a name for himself as a television star. This is not an unusual career path for presidents; Joseph Estrada had been a prolific film actor before being elected president. The other celebrity in the running for president is Manny Pacquiao, who once gained international fame as the welterweight world champion boxer before entering the equally combative arena of Philippines politics. After retiring from boxing, Pacquiao served in the National Assembly from 2010 to 2016 and since then has served in the Senate.

Thus far, however, neither Moreno nor Pacquiao seems to have been effective in converting their celebrity into political support – according to one recent survey, they are polling at four per cent and seven per cent, respectively.

Between the Old and the New

The Persistence of ‘Trapo’ Politics

“Trapo” is a Tagalog shorthand for “traditional politics.” But its literal definition means a “wiping rug” – something that becomes dirtier the more it is used. This word is often used pejoratively to refer to politicians who promise to provide hope for the people yet use dirty tactics to gain support during elections, such as violence, coercion, and fraud. Despite their charismatic leadership, politicians who engage in Trapo foster patron-client ties and tend to come from an oligarchic and patrimonial elite.

Powerful Families

The power of political dynasties is another longstanding feature of politics in the Philippines and shows no signs of abating. As noted above, Bongbong Marcos is the son of the long-serving dictator, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. Some observers attribute his strong performance thus far in pre-election polling to the unparalleled prominence of the family name. While Marcos Sr. instituted martial law (1972-1981), presided over widespread human rights violations, and is believed to have stolen billions of dollars from the country, he is still revered by many in the Philippines as a great leader. Many of these loyalists believe Marcos Jr. will be the same.

The other dynasty-in-the-making is on the vice-presidential ticket, namely, the candidacy of Sara Duterte, daughter of incumbent President Rodrigo Duterte. Sara Duterte currently serves as mayor of the southern city of Davao, the post her father held for 22 years. Her two brothers are also prominent in politics – Duterte’s eldest son Paolo serves in the House of Representatives, and another son, Sebastian, is vice-mayor to his sister Sara.

The criticism inherent in the reference to Trapo politics at least hints at an interest in seeing newcomers in politics. At the same time, support for familial dynasties runs deep: An astounding 67 per cent of the seats held in Congress are from political dynasties. In the May 9 election, these two tendencies will present voters with a stark choice: Either a president who comes from dynastic rule (Marcos) or one whose campaign is moving away from elite interests to focus instead on the masses (Robredo).

What’s Next in This Series

The rest of the Dispatches in this series analyze several major themes. Considering the international attention to Duterte’s War on Drugs, we start with a discussion on what might happen to this policy after a change in leadership.

We next discuss the Philippines’ foreign policy and its economic ties to China and the U.S. Rather than suggesting that the Philippines must choose between the two superpowers, we consider some of the complicated approaches that the candidates might take.

Due to ongoing campaign restrictions because of COVID-19, social media platforms are central to candidates’ engagement with the public. In this context, how is misinformation spreading online during the elections, and how was the media landscape vulnerable to these activities even before this election period?

We then turn to why the Marcos legacy looks like it is ready to make a major comeback in this election. We outline how historical revisionism and authoritarian nostalgia might inform the next generation’s voting decisions.

Finally, we cap off the series with a focus on the transnational dimension of the elections, specifically, the Philippines’ approach to labour migrant workers. In doing so, we also consider the possible implications for Canada.

Of course, these election issues are not independent of one another, nor can they be understood in isolation. However, we hope that this series will help to outline some of the challenges for the next president of the Philippines, as well as what is ultimately at stake for the Philippines’ democracy.