As it slowly emerges from its worst-ever recession, caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Philippines will have an opportunity to determine the type of recovery ahead when it selects its new president on May 9. By extension, the election will also be a significant moment for Philippines-China relations; economic ties between the two countries have strengthened during the current presidency of Rodrigo Duterte. The top two candidates competing to succeed him have laid out policies to boost the economy and reduce unemployment. Whereas deeper ties with Beijing could help them in their efforts, closer relations may come with serious risks, including to the Philippines’ sovereignty concerns related to the South China Sea.

The candidates and the China question

Senator Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. is running for president, a seat once held by his father, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. Bongbong has led the polls for several months. He supports Duterte’s bilateral approach toward Beijing, which is to say he would honour a range of economic co-operation agreements signed between the countries and would lean toward solving any disputes between his government and Beijing directly rather than through multilateral forums – which is also how Beijing prefers to deal with such matters. As part of his campaign, Marcos is promising to modernize the country’s infrastructure, which can be seen as a continuation of Duterte’s so-called Build-Build-Build plan, inclusive of large Chinese investments.

Current Vice-President Maria Leonor “Leni” Robredo is Marcos’ main contender, running a distant second but narrowing the gap as the candidates reach the homestretch. She has criticized Build-Build-Build as too costly but says infrastructure would remain a priority for her administration. She has emphasized projects to boost agriculture, a sector hit hard by the pandemic’s economic downturn and supports building farm-to-market roads and storage facilities.

While Marcos’ campaign foreshadows close relations with Beijing, Robredo has encouraged closer ties to other Asian countries and with the Philippines’ traditional ally, the United States. During an October speech at the Rotary Club of Manila, Robredo said if she is elected president, Philippine-Chinese joint projects in the South China Sea (SCS) will depend on Beijing recognizing a 2016 arbitral ruling at The International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, in which the international body rejected China’s historic claims to much of the SCS. The case was pursued by former President Beningo Aquino Jr. Robredo was a member of Aquino’s Liberal Party before deciding to run as an independent. The Philippine government continues to say illegal Chinese fishing and militarization are taking place within its 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone, which it refers to as the West Philippine Sea. China’s so-called Nine-Dash Line, which marks its SCS claims, has also led to disputes with other Southeast Asian countries, such as Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam.

Duterte’s pivot to China

At the outset of his presidency six years ago, Duterte sought to reduce the distance between the Philippines and China resulting from the ICJ ruling. During a state visit by Chinese President Xi Jinping to Manila in 2018, the two countries signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to jointly explore oil and gas at the Reed Bank (known in the Philippines as Recto Bank) in the contested Spratly Islands. It is believed to hold 165 million barrels of oil and 3.4 billion cubic feet of gas. The entire South China Sea is estimated to have deposits one hundred times those amounts. The Reed Bank also conveniently sits near the existing infrastructure of the Malampaya gas field, which is predicted to be depleted by 2027.

A total of 29 MOUs were signed during Xi’s 2018 visit. Other agreements included building bridges in the southern cities of Davao and Marawi (the former being Duterte’s hometown), a dam in Rizal province, and industrial parks. Duterte says the next president should honour these agreements. With his daughter and current Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte leading the polls in the race for vice-president, it's likely there will be a strong force for continuity within the next administration if she and Marcos both prevail.

China shares the top spot with the U.S. as the Philippines’ largest trading partner, and recent developments support further Chinese investment. Since it was established in 2016, the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) has financed Philippine projects worth more than US$1.5 billion.

The Philippines has also become the largest supplier of nickel ore to China after Indonesia banned its export in 2020. Chinese investment in mining is set to grow following Duterte’s lifting of bans on new and open-pit mines last year. With rich deposits in nickel, copper, gold, and other minerals and metals, mining is increasingly seen as a way to boost the Philippines’ struggling economy. Nearly all the presidential candidates, including the frontrunners, support developing the sector.

The Philippines is a member of the Beijing-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which came into effect in January. The 15 Asia Pacific member countries have promised to phase out trade barriers. As the sole superpower member, China and its companies stand to gain. It is important to note, however, that despite the power imbalances, RCEP has the potential to facilitate increased trade with other major investors like Australia and Japan. Reducing trade barriers is also a goal of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which the Philippines is a founding member. Canada and the United Kingdom are currently pursuing free trade agreements with ASEAN.

Navigating the South China Sea issue

Although Manila and Washington have had a Mutual Defense Treaty in place since 1951, the Philippines edged closer to China during the U.S. presidency of Donald Trump. Recent developments suggest there has been somewhat of a reversal since President Joe Biden took office. Joint military drills restarted last year after the Philippine Coast Guard identified more than 200 Chinese vessels at the Whitsun Reef in the Spratly Islands. Most of the vessels left weeks later, but the standoff has complicated progress on surveying oil and gas deposits at the Reed Bank. At the time of writing, the Philippines’ Department of Energy has put a hold on surveying, presumably leaving the next president with the responsibility to engage the issue.

Duterte twice renewed the U.S.-Philippines Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), allowing the deployment of U.S. troops in the country. His government also signed a $US368-million contract for Russian and Indian-made BrahMos supersonic cruise missiles. In a thinly veiled reference to China, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana described the shore-based anti-ship missile system as “deterrence against any attempt to undermine our sovereignty.”

Public opinion polls show 77 per cent of Filipinos support strengthening their military in response to concerns about the SCS issue, and a clear majority want alliances with other countries to help. Although other ASEAN nations also have territorial disputes with China, the regional body has been unable to foster a resolution. Negotiations could either be helped or hurt by the emergence of the Quad, a security partnership between the U.S., Japan, Australia, and India that has emphasized freedom of navigation in the Indo-Pacific region and is, in effect, an initiative to contain the impact of China’s growing international power.

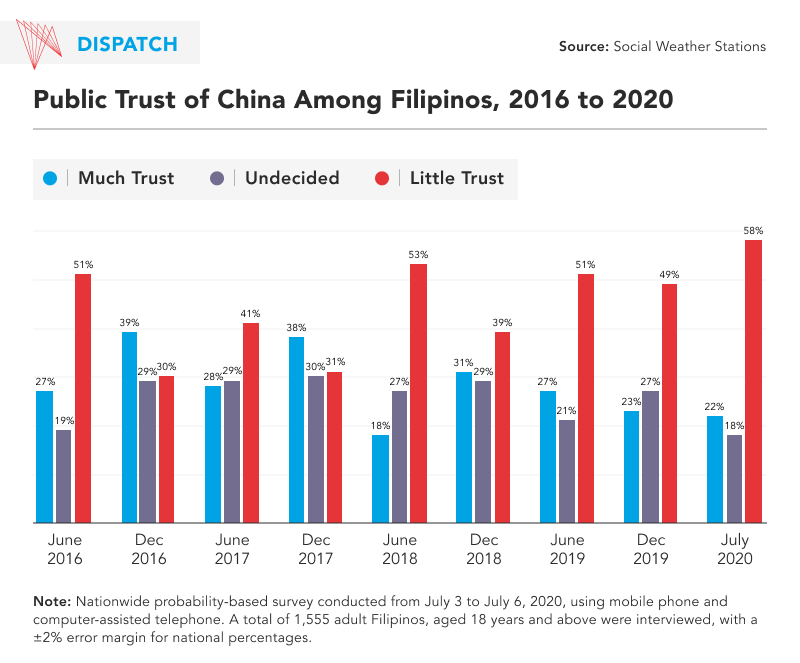

Balancing between superpowers in the SCS will be a significant challenge for the Philippines’ next president. China has become a major source of the country’s imports and exports. A sudden withdrawal of Chinese investments could damage the Philippine economy. This balancing act will also be important domestically. Public opinion polls suggest Filipinos increasingly view China negatively, and the majority don’t trust their neighbour.

Challenges ahead

Whichever presidential candidate enters Malacañang Palace on June 30 must quickly learn to manage a complicated relationship with China. At the onset of his six-year term, Duterte appeared to fully embrace Beijing, even at the cost of maintaining strong relations with the country’s traditional allies. But his actions later in his presidency suggest a pivot back towards the U.S., most notably resuming joint military drills. The government has welcomed Chinese investment, a trend unlikely to change as the next administration tries to create opportunities for millions of unemployed Filipinos. Pressure to develop oil and gas in the contested Reed Bank will mount as the county eyes a depletion of existing offshore gas in the coming years. High global energy prices have added to the urgency for action. Senator Marcos has leaned towards continuing a close relationship with China, whereas Vice-President Robredo favours focusing on partnerships with other countries, particularly to solve the Philippines’ territorial disputes with China. Moving forward, a strategically diverse set of military and economic partnerships could benefit the Philippines as it tries to recover from the coronavirus pandemic. The next president will have to find the right balance.