The COVID-19 pandemic has affected more than 90 per cent of the global student population, causing one of the largest disruptions in the history of formal education. Even prior to the pandemic, one out of every five children, adolescents, and youth globally were out of school. Educational opportunities have long been unequally distributed across genders, income groups, geographies, and other demographics – inequalities that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Education in Nepal has been no exception to this trend. The unevenly developed South Asian nation of 28.6 million people has long dealt with structural challenges in delivering quality education to its population. Despite significant strides in education, almost half of the population still remains illiterate, a situation exacerbated by unequal socio-economic conditions and limited technological infrastructure. These pre-existing concerns have hampered the Nepali education sector’s response to the global pandemic.

Remote learning without connectivity

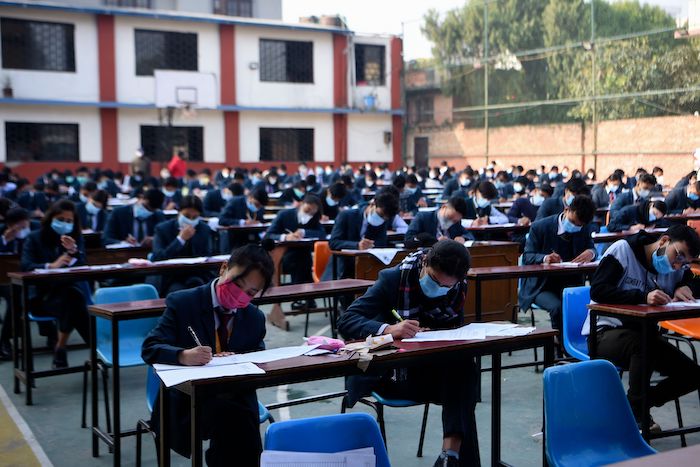

According to Nepal’s Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, the nation is home to approximately seven million students, with more than five million enrolled in government funded public schools between 2017 and 2018. On March 18, 2020, the federal government closed all schools and colleges in the country in order to limit the spread of COVID-19. However, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MoEST) recently directed municipal governments to reopen schools at their discretion, with proper health and safety measures, including shift-based classes. This has resulted in some schools opening in Nepal, particularly in the Kathmandu Valley, which is a hotspot for COVID-19 infections, posing a risk for senior citizens.

In the meantime, there have been attempts to continue classroom learning remotely, through broadcasts on television and radio and online platforms, though virtual options remain difficult in a country where access to internet and computers is unevenly distributed. In fact, most schools don’t have internet connectivity, as noted in the 2019-20 Economic Survey (Ministry of Finance), which reported that only 12 per cent of public schools have the capacity to offer information and communication technology- (ICT) based learning.

Navigating the digital divide, structural challenges

In the face of such challenges, many in Nepal have tried to get the education of young Nepalis back on track. Rabi Karmacharya is one of those seeking solutions. Since 2007, he has been working as Executive Director of Open Learning Exchange (OLE) Nepal, a social benefit organization he helped found, to improve education in Nepal through increasing technological connectivity. That work may now be more important than ever.

OLE’s approach has included distributing computers and an interactive learning software to schools throughout Nepal, as well as providing training for teachers to best utilize these tools. Through a rapid collaboration with Nepal’s MoEST in March 2020, OLE worked to make educational content available with free and open access for all learners through the Ministry’s online education portal.

Despite such efforts, serious obstacles remain for Nepal’s public education system. Not least of these is a lack of co-ordination between decision makers at different levels of government. Nepal has been transitioning to a federal system from a unitary government since 2017, giving rise to new provincial and municipal levels of government. Despite the transition, many COVID-19 response decisions have been made by the central government, while local authorities have lacked the resources and institutional structure necessary to forge their own paths. Teachers and civil society organizations have also indicated that local governments waited for directives from central authorities, which did not have a clear idea or plan to address the problems.

Data and gender challenges

As decision makers at different levels have sought to address the impacts of the pandemic on education in Nepal, one of the primary challenges has been a dearth of up-to-date and accurate data. Though the government has been collecting school-level academic performance data through its education management information system (EMIS) since 2004, it lacks current data regarding the impact of the pandemic on students and teachers.

Beyond the lack of data regarding connectivity in schools and homes, there are questions around how the pandemic has impacted already-existing disparities in the education system. If access to quality education in the best of times has been inequitable across urban and rural settings, genders, and other elements of individual and community identity, what is happening now?

Researchers from institutions like UNESCO, UN Women, and the University of British Columbia have speculated about the disproportionately negative impact of the pandemic on women and girls in Nepal based on analyses of current impacts elsewhere and historical evidence, like the results of the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. However, not much is known about the current and future impacts of COVID-19 on girls’ education in Nepal, and education across urban and rural settings.

Fostering partnerships to ensure that communities implement gender-sensitive responses to improve the quality and access to education remains a systemic challenge, but is crucial towards addressing gender disparities in education. Such initiatives are much more impactful when implemented at the local level.

Education policy responses across South Asia

While Nepal’s struggles handling the pandemic’s impact on education may be particularly daunting, they are far from unique.

Although most South Asian governments are making substantial efforts, their capacity to provide quality education – especially for their most disadvantaged populations – varies greatly. Approximately 144 million children, or close to 38 per cent of school children in South Asia, are unable to access digital learning. Less than 25 per cent of low-income countries currently provide any type of remote learning, and of these, the majority are using TV and radio. In contrast, close to 90 per cent of high-income countries are providing remote learning opportunities, nearly all of which are provided online.

The World Bank’s systematic review of government COVID-19 education response plans notes that South Asian countries were three times more likely to refer to online interventions than offline initiatives despite the fact that online learning can reach only seven per cent of the students. Meanwhile, offline interventions such as television and radio have the potential to reach around 60 per cent.

In India, both central and local levels of government faced pressure to respond to the unprecedented situation wrought by the pandemic with limited data, inadequate digital infrastructure, and a lack of technology-trained teachers. However, the central government had launched digital educational initiatives like the Mantri e-Vidya Initiative through the oversight of local governments. India’s example demonstrates the potential for Nepal to encourage local government discretion for implementing existing educational initiatives that have a targeted impact on students, considering regional challenges and opportunities.

In India, both central and local levels of government faced pressure to respond to the unprecedented situation wrought by the pandemic with limited data, inadequate digital infrastructure, and a lack of technology-trained teachers. However, the central government had launched digital educational initiatives like the Mantri e-Vidya Initiative through the oversight of local governments. India’s example demonstrates the potential for Nepal to encourage local government discretion for implementing existing educational initiatives that have a targeted impact on students, considering regional challenges and opportunities.

Bangladesh provides another perspective, as its unified governance approach proved to be well-positioned in response to COVID-induced school closures. Prior to the pandemic, Bangladesh worked on strengthening online and remote education through ‘Digital Bangladesh,’ a program designed to increase access to public services, including education at the local level. The nation’s COVID-19 response was emboldened by an ongoing process of producing an extensive, alternative education strategy. As Nepal’s non-unitary government has currently designated education policies at the central level, Bangladesh’s model is illustrative of a stronger system where some jurisdiction can be employed at the municipal level.

Bangladesh provides another perspective, as its unified governance approach proved to be well-positioned in response to COVID-induced school closures. Prior to the pandemic, Bangladesh worked on strengthening online and remote education through ‘Digital Bangladesh,’ a program designed to increase access to public services, including education at the local level. The nation’s COVID-19 response was emboldened by an ongoing process of producing an extensive, alternative education strategy. As Nepal’s non-unitary government has currently designated education policies at the central level, Bangladesh’s model is illustrative of a stronger system where some jurisdiction can be employed at the municipal level.

In reference to the aforementioned examples from South Asian countries, inter-ministerial and subnational collaboration ensures that schools are being supported and will improve the quality and access to education in the era of COVID and beyond. Where Nepal has struggled to respond to the pandemic in this vein, there is opportunity for improvement by clearly defining the specific roles and responsibilities of different levels of government and ensuring that local governments have the resources and capacity they need to fulfill their responsibilities.

Meanwhile, the full impact of the pandemic on learning outcomes remains to be seen. However, it is more urgent now than ever to converge policy responses across international organizations, different levels of governance, and school administration with a focus on maximizing learning opportunities for students most affected by the perils of remote education. The way Nepal handles this crisis now may well impact students for years to come.

Nabila Farid, Boyd Hayes, and Riya Sirkhell are graduate students specializing in Development and Social Change at the Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs (MPPGA) Program at the University of B.C. They are currently working with Open Learning Exchange Nepal and Nepali Master’s student Ujjwal Neupane at the Tribhuvan University Central Department of Anthropology to design and implement a research project about policy responses to the challenges posed by the pandemic to education in Nepal.