Artificial Intelligence (AI) is poised to transform the global economy, and Canada’s leadership in this technology presents a unique set of opportunities in the Asia Pacific.

The policy brief Towards Canada’s Asia Strategy on AI outlines and argues for a comprehensive and long-term strategy that addresses Canada’s challenges and opportunities in its commercial, people-to-people, and geopolitical engagements in Asia as they relate to AI.

The brief by APF Canada researcher Dongwoo Kim also provides four policy recommendations for the Government of Canada for the development of a comprehensive and dynamic Asia Strategy on AI for enhanced engagement with the growing economies of the Asia Pacific.

Introduction

Why an Asia Strategy on AI?

In recent years, the importance of developing targeted strategies to pursue opportunities in the Asia Pacific – that is, ‘Asia Strategies’ – has come to the forefront of policy discourse.[1] As noted in global strategy advisor Parag Khanna’s bestseller, The Future is Asian, Asia is increasingly becoming more prosperous and confident. For Canada, sustained engagement with this region is now critical to the country’s long-term economic prosperity. Propelled by its young population and increase in productivity, Asia is predicted to make up 65 per cent of the world’s global middle class by 2030 and it is expected to account for 53 per cent of the world’s population and 52 per cent of global GDP by 2050. The need for trade diversification and deeper engagement with Asia is clear, but Canada often falls short of the Asia-specific skills, resources, and, most importantly, strategies that are required to take advantage of these opportunities. In this context, enter artificial intelligence (AI).

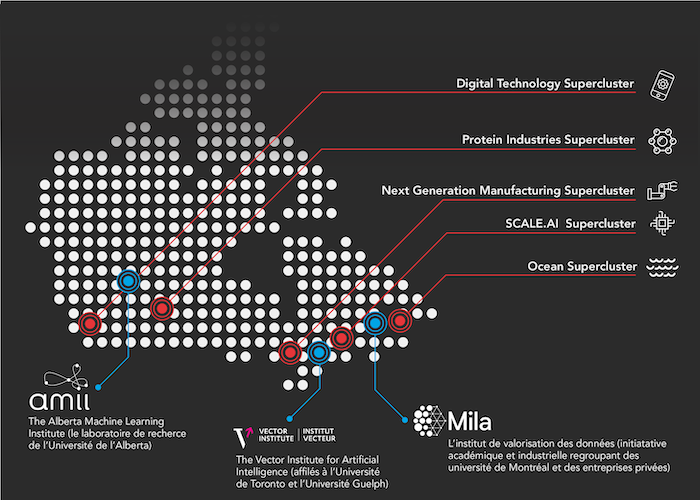

Early investment in basic research in AI has made Canada home today to world-leading researchers such as Yoshua Bengio at Université de Montréal, Geoffrey Hinton at University of Toronto, and Richard Sutton at University of Alberta.[2] Their research and teams have attracted investment to Canada from global firms such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook. Recognizing this potential, the Government of Canada has invested C$125 million in the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy, establishing research clusters in Toronto, Montreal, and Edmonton to maintain Canada’s edge in AI, and Global Affairs Canada has begun promoting ‘Canadian AI’ abroad. Add to this the creation last year of Canada’s Innovation Superclusters Initiative – a five-hub initiative to integrate cutting-edge technologies – including AI – into regional industries, and Canada’s potential to ‘punch above its weight’ in emergent technology sectors certainly becomes apparent.

This document argues that an effective ‘Asia Strategy on AI,’ if developed, could be an entry point for Canada’s greater engagement in the Asia Pacific. To this end, the policy brief outlines different target areas for Canada’s engagement on AI in Asia: trade and investment, people-to-people engagement, and geopolitics. Each sector complements the other, building the case for a broad strategy that brings together policy-makers, academics, and industry stakeholders. While this type of strategy is applicable to many sectors in Canada, this policy brief highlights AI as an area where an Asia Strategy that brings together government, industry, and civil society would be greatly beneficial considering Canada’s current strength in AI, the unique nature of the technology, and the transformations that the Asia Pacific region has been undergoing.

Canada’s strength in AI today can translate into assets in its foreign affairs, especially vis-à-vis Asia, as will be outlined in this document. Canada’s Asia Strategy on AI should be comprehensive and multifaceted, and it should encompass various sub-strategies in order to effectively address Asia’s diverse markets. Further, the Strategy should be dynamic, reflecting rapid, emerging changes and inputs from relevant stakeholders.

Why Does AI Matter?

AI broadly refers to computing programs that simulate human intelligence to achieve tasks. Today, most of the conversations about AI refer to a specific sub-sector called machine learning (ML), in which computers learn and improve their performance of certain tasks based on data. AI can be applied to basically all sectors of society and the economy to automate and thereby improve the efficiency of operations. From Facebook newsfeeds that select most relevant items for each user to autonomous vehicles soon to roam our streets, AI will play an increasingly significant role in all of our lives.

AI promises increased efficiency and therefore, productivity gains. According to a widely-cited PwC report, AI is expected to add US$15.7 trillion to the global GDP by 2030.[3] Governments and firms around the world have therefore started to race to take advantage of the AI opportunity since the mid-2010s, and the rush is not going to end anytime soon. Andrew Ng of Stanford University said, “just as electricity transformed industry after industry 100 years ago . . . AI will now do the same,” underscoring the heightened expectations around this disruptive technology.[4] Perhaps the current excitement around AI will dissipate, but the technology itself will continue becoming more entrenched in all aspects of our lives.

At the same time, AI poses a new type of challenge for policy-makers. The substitution – whether partial or complete – of human agency with algorithms entails ethical, legal, and social implications and requires a revision of existing governance frameworks. While data is often compared to oil,[5] its political, social, and economic dimensions, as well as its functional qualities, altogether distinguish it from oil or other resources, and present an unprecedented set of challenges for policy-makers in extracting and leveraging it for practical applications (e.g. consider the recent controversy over Toronto Sidewalk Labs’ tech-driven vision for the city[6]). The consideration of AI governance at a greater scale – both national, regional, and global level – also poses an unprecedented, multi-layered dilemma for stakeholders in policy, industry, and civil society, increasingly demanding an urgent response.

Why Asia?

Today, Asian states are rushing to seize the AI opportunity to boost their productivity and improve the lives of their citizens. Countries like China, Japan, and South Korea have laid out national strategies that stretch beyond the promotion of R&D and address actual deployment of AI across society and the economy by actively facilitating collaboration between policy-makers, the private sector, and researchers. Conforming to the model that political scientists refer to as ‘developmental state,’[7] Asian states see AI as a factor that will allow them to either maintain or gain competitiveness in the global stage. They are therefore launching these comprehensive initiatives with the same approach they took to propel rapid economic growth and modernization during the last century. For instance, China has articulated its goal to become ‘number one’ in both AI research and deployment by 2030, and South Korea has also announced its ambition to become one of the ‘Top 4’ in AI by 2022. According to Kai-fu Lee, a renowned AI scientist and author of AI Superpowers, what matters in AI is not coming up with the best research but having a setting where AI-run products can be deployed – and Asian states are actively creating such environments.[8]

Considering current economic and technological trends, AI will play a particularly important role in Asia, especially in developing countries. As stated in a 2018 International Development Research Centre (IDRC) White Paper, AI applications offer great possibilities for promoting economic growth and tackling long-standing problems in the Global South, in areas such as health care, government services, agriculture, education, and the economy and business.[9] Canada could gain not only through early commercial engagement that leverages AI in South and Southeast Asia, but also by contributing to the region’s development policy as a responsible international player.

[1] The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, Building Blocks for a Canada-Asia Strategy (Vancouver: The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, 2016), https://www.asiapacific.ca/sites/default/files/filefield/asia-strategy-report-eng.pdf

[2] The Economist, “How Canada’s unique research culture has aided artificial intelligence,” The Economist, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2017/11/04/how-canadas-unique-research-culture-has-aided-artificial-intelligence (November 4, 2017).

[3] PricewaterhouseCoopers, Sizing the Prize: What's the Real Value of AI for Your Business and How Can You Capitalise? (Boston: PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2017).

[4] Matt Burgess, “Is AI the new electricity,” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/future-focused-it/2018/nov/12/is-ai-the-new-electricity (November 12, 2018).

[5] Bernard Marr, “Here’s why data is not the new oil,” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2018/03/05/heres-why-data-is-not-the-new-oil/#73a545c83aa9 (March 5, 2018).

[6] Donovan Vincent, “#Blocksidewalk says there’s a ‘power asymmetry’ between the city and Sidewalk Labs,” The Star, https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2019/05/01/blocksidewalk-says-theres-a-power-asymmetry-between-the-city-and-sidewalk-labs.html (May 1, 2019).

[7] Stephan Haggard, Developmental States (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[8] Kai-fu Lee, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018).

[9] Sujaya Neupane and Matthew Smith, Artificial intelligence and human development: toward a research agenda (Ottawa: IDRC, 2018).

Trade & Investment

A Two-Pronged Approach

While the need for Canada to strengthen commercial ties with economies in the Asia Pacific has been stressed with frequency, the window of opportunity may be closing. According to McKinsey’s Asia’s Future is Now, the regional economy in the Asia Pacific has been shifting – with industry value chains relying more heavily on R&D, innovation, and local consumption, along with 52 per cent of trade now being intra-regional.[1] At the same time, these Asian countries are in the process of digitalizing their economies – especially in manufacturing – and Canadian expertise on AI would be useful at this juncture, with Canadian firms that offer AI as a service (AIaaS) finding significant opportunities.

In approaching trade and investment opportunities on AI with Asia, Canada should develop an Asia Strategy that differentiates two main types of stakeholders: developed countries in (mostly) the northeast and developing countries in the south.

Developed Countries

The need for engagement on AI with economically- and technologically-advanced economies such as China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan is obvious, and Canadian stakeholders have already started engaging with these countries at different levels. These countries have the capital to invest in Canadian AI entrepreneurs, and they are also scientifically-advanced, innovative countries that have existing academic and research exchanges with Canada.

Companies from these developed countries are investing heavily to gain access to Canada’s AI talent. Five out of seven investment deals on AI signed in 2017 and 2018 came from East Asian conglomerates (Samsung, LG, Didi, and Fujitsu), totalling C$313.7 million, according to APF Canada’s Investment Monitor.[2] Companies such as Samsung, LG, Huawei, and Fujitsu have established research partnerships and centres in numerous Canadian cities, and policy-makers have taken notice. Further, there is a natural, complementary match between a strength in hardware manufacturing and application in these countries and Canada’s edge in basic research and software. During Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s visit to Ottawa, recent investments in Canadian research centres by Mitsubishi, Fujitsu, and Denso were highlighted, further underscoring the importance of AI in Canada’s economic relations with developed countries in Northeast Asia.[3] In this context, an Asia Strategy on AI should find ways of further supporting investment attraction from Asia to Canada, which thus far has focused on conglomerates with the capacity to set up international operations.

However, a more strategic approach to AI opportunities in Asia based on in-depth research could lead to greater opportunities in trade and investment. For instance, in South Korea and Japan there are small-and-medium enterprises (SMEs) that could benefit from access to Canada’s AI talent, but they do not have the capacity to establish research centres like conglomerates such as Samsung or Toyota have done. In Asia, SMEs comprise 98 per cent of enterprises and employ 50 per cent of the workforce.[4] Exploring creative ways of connecting Asian SME’s with Canada’s AI talent would allow Canada to further realize its potential in Asia.

Finally, it is important for Canada to think long-term when considering its comparative advantage in these countries. AI will continue being an important part of our lives, and countries around the world are racing to increase their AI talent pools by establishing new training programs and funnelling financial support. In this context, Canada could risk losing its current comparative advantage that relies heavily on its talent pool. In their national AI strategies, China, Japan, and South Korea all make it very clear that their long-term goal is to develop their own domestic talent pools. The ‘rush’ to Canadian AI talent provides a temporary stop-gap, but there is no guarantee this advantage will remain in the long run. Canadian policy-makers and industry stakeholders must think of ways of continuing to provide a value-add in AI to Asia in the long-term, leveraging Canada’s current profile as a leading AI R&D nation.

Developing Countries

A less obvious place to look for trade and investment opportunities in AI is Southeast and South Asia, especially the countries with strong growth potential. Most of these countries lack the necessary strengths in R&D or digital infrastructure, which are opportunities in and of themselves for Canadian AI in Southeast and South Asian economies.

Projections indicate that countries like Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Vietnam will grow significantly through the first half of the twenty-first century.[5] Indonesia’s GDP, for instance, is projected to reach US$10.5 trillion by 2050, making it the fourth largest world economy. While not as impressive in scale, the GDP in the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia will all grow three-fold, reaching US$3.3 trillion, US$2.8 trillion, and US$3.2 trillion, respectively. Beyond AI, the ASEAN countries will become important economic partners for Canada moving forward, spurred by the CPTPP, which came into force in December 2018.

Economic development in these countries will be accompanied by AI. Understanding the potential of the technology for delivering economic growth and improvements in quality of life, states in Southeast and South Asia are racing to support R&D and the deployment of the technology. The Philippines, for instance, emphasized the need to “vigorously” advance science, technology, and innovation for economic development in its five-year plan, Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022.[6] Vietnam came up with the ‘Industry 4.0 Strategy’ (July 2019), which aims to position the country as the leading digital economy of ASEAN by 2030 through integration of AI.[7]

In addition to the policy interest in promoting AI, young people in these countries are becoming not only increasingly more productive, but also more tech-savvy. The internet economy in Southeast Asia hit US$50 billion in 2017 and it is expected to reach US$200 billion by 2025.[8] By 2020, the region will have 480 million internet users. Burgeoning start-up scenes in cities such as Hanoi and Manila further underscore the likelihood of AI becoming a significant growth driver in these economies.

Considering the growth potential of these markets and the growing importance of AI in economic development, there is a potential window of opportunity for Canadian AI practitioners to be proactive in developing countries in Asia and to become the “first movers.” If we extend the metaphor of AI as electricity,[9] imagine having invested in electricity infrastructure amid its early expansion into society. AI presents a similar long-term opportunity for forward-thinking Canadian businesses and entrepreneurs. Considering the growing role of AI in trade, investment, and development, there is also the potential of participating in finding ways of tying ‘responsible,’ ‘ethical,’ or ‘human-centric’ AI into a progressive trade agenda (PTA) that engages like-minded partners not only in AI, but across multiple sectors.[10]

[1] McKinsey Global Institute, Asia’s Future is Now (New York City: McKinsey Global Institute, 2019).

[2] The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, The Investment Monitor.

[3] Government of Canada, “Canada announces closer collaboration with Japan,” Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, https://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2019/04/28/canada-announces-closer-collaboration-japan (April 28, 2019).

[4] Asad Ata, “The Role of SMEs in Asia’s Economic Growth,” SME Finance Forum, https://www.smefinanceforum.org/post/the-role-of-smes-in-asias-economic-growth.

[5] PricewaterhouseCoopers, The Long View: How will the global economic order change by 2050? (Boston: PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2017).

[6] National Economic and Development Authority, Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022 (Manila: National Economic and Development Authority, 2017), http://pdp.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/PDP-2017-2022-07-20-2017.pdf.

[7] Ministry of Planning and Investment, Industry 4.0 Strategy, http://www.mpi.gov.vn/Pages/tinbai.aspx?idTin=43597&idcm=311.

[8] Rayna Hollander, “Southeast Asia could be a leader in mobile internet usage next year,” Business Insider, https://www.businessinsider.com/southeast-asia-could-be-a-leader-in-mobile-internet-usage-next-year-2017-12 (December 13, 2017).

[9] Lee, AI Superpowers.

[10] Dan Ciuriak, Canada’s Progressive Trade Agenda: NAFTA and Beyond (Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, 2018), https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed/Final%20June%2011%20Commentary_516.pdf.

People-to-people Engagement

Talent and Ethics

Technology is difficult to govern as it often does not exist in material form. Governments can develop ethics guidelines and sign regulatory agreements on technologies, but they will not be effective unless there is sustained people-to-people engagement, especially between scientists and engineers. Canada’s AI strategy in Asia, therefore, must incorporate a people-to-people engagement aspect. Further, Canada has the potential to lead in the promotion of ethical uses of AI by leveraging its talent, which provides a great window of opportunity as it seeks to embed progressive values in international governance through its larger foreign policy.

Talent

There is a global shortage of AI talent, which provides an important opportunity for Canada. National AI strategies in China, Japan, and South Korea all acknowledge the lack of domestic AI talent. Each of these three governments has invested substantially in academic and vocational training programs to meet the talent gap, in addition to financially capable companies establishing research centres in North America and Europe. Canadian AI academics and research institutes from Edmonton to Toronto are already dominating this space, and Canada could be more ambitious in leveraging these assets.

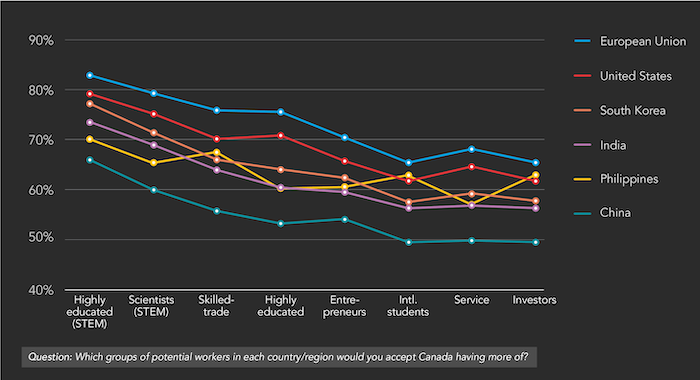

Public opinion polls in Canada support the attraction and retention of international talent. For example, according to APF Canada’s 2019 National Opinion Poll: Canadian Views on Human Capital from Asia, a majority (56 per cent) of Canadians believe that Canada’s shortage of high-skilled workers is becoming “a deterrent to its competitiveness in the global economy,” and agree that Canada should look to Asia for international talent in the next 10 years.[1] Further, 74 per cent believe that highly-educated individuals with STEM skills “deserve further attention in [Canada’s] immigration policy.”[2]

Canada could do better in attracting, training, and retaining the best and the brightest in AI. Canada’s post-secondary sector has been increasingly attracting more international students, especially those from Asia. The number of international students hit a record year in 2018, with 572,415 as of December 31, a 17 per cent increase over 2017.[3] India surpassed China as the top sender of international students with 172,625, a whopping 40-per-cent increase over 2017. China (142,985) and South Korea (24,195) follow. International students bring revenue to universities and local economies (C$2.75 billion for universities in 2015-16),[4] and they become part of the Canadian network when they move back to their home countries, strengthening Canada’s national brand. Canadian universities are globally renowned for their AI research and the current interest in the technology provides yet another reason for international students to choose Canada. Particularly as the U.S. continues to draw its ‘tech iron curtain’ and limit Chinese access to its research institutes, Canadian post-secondary institutions should capitalize on this opportunity to further attract and retain international talent.[5]

The Government of Canada has invested C$125 million in the Pan-Canadian AI Strategy (2017), which has boosted the research capacity of the country’s three leading AI institutes (Edmonton, Montreal, and Toronto), taking a step in the right direction in attracting, training, and retaining high-level AI talent. It is important that this effort continues beyond Strategy’s five-year period. According to the report Reversing the Brain Drain by Brock University, however, 66 per cent of software engineering students leave Canada for work after graduation, with 82 per cent of those who leave going to the U.S. While the U.S. is the main destination of this ‘brain drain,’ Canada must increasingly consider the loss of AI talent to Asia, where national governments are racing to promote AI research and commercialization. Particularly in China, companies have been recruiting AI talent from abroad, offering high salaries (top engineers reportedly being compensated US$1 million per annum) at globally-renowned firms. Stakeholders in Canada must consider incentives to retain talented AI researchers in the country, especially upon graduation.[6] Further, there is a need to look beyond research institutes and consider the quality of industry opportunities for AI talent. In this context, there is a need for government, academia, and industry to collaborate in creating substantial commercial opportunities to retain Canada-trained talent in Canada.

But it is also important to leverage Canada-trained talent that does move back to Asia. Graduates from Canadian universities could become ambassadors and an important part of the global network that could help Canadian academics, policy-makers, and entrepreneurs gain a toehold and seize upon the opportunities available in their respective countries. An Asia Strategy in AI that considers talent within a more comprehensive context like this would greatly enhance Canada’s ability to attract and retain talent, as well as achieving its policy goals abroad.

Canada as a Champion of Ethical AI

As AI became an increasingly important part of the public debate, experts have raised concerns over its potential malicious uses[7] and thus discussions around AI ethics have become an important issue. The Japan’s AI community developed an ‘AI R&D Guideline’ prior to the G7 meeting in 2016, and the European Union released the ‘Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI’ in April 2019.[8] Université de Montréal also released the ‘Montréal Declaration on Ethical AI.’ It is important to understand that the outpouring of ethics guidelines not only addresses real concerns over the potential malicious uses of the technology, but also reflects the global contest over the ‘norms’ of AI use, which touches upon cultural, social, and political aspects.

Canada’s AI talent is an asset for becoming a leader in the promotion of ethical uses of the technology that reflect Canadian values. Certainly the community of AI experts is small, largely academic, but promotion of good practices in Canadian AI research institutes can shape good practices abroad, when graduates from Canada move or return abroad. Influential AI academics, therefore, have a major role to play in promoting ethical uses of AI. Turing Award-winner Yoshua Bengio, a computer scientist at the Université de Montréal, has been instrumental in the campaign to ban the development of lethal autonomous weapons, for instance.[9] Leveraging this particular form of influence in combination with efforts in research collaboration, trade, investment, Track II-level dialogues, and eventually formal diplomacy could allow Canada to exercise leadership in the promotion of ethical uses of AI in all relevant frontiers.

Further, engagements with Track II-level stakeholders in Asia on AI ethics would create an ideal foundation for government-to-government dialogues on the international regulation of the technology. Due to the technological and global nature of AI, effective regulation requires buy-in from and continued engagement by academia, industry, and policy-makers.

Canada can lead by facilitating these dialogues on ethics, and it has the international reputation – both diplomatic and technical – to become the international centre of AI governance. The next two years present key opportunities, as Vancouver will host the Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) in both 2019 and 2020. As AI practitioners convene from all around the world for the largest global AI academic conference, a valuable opportunity presents for relevant stakeholders to facilitate discussions on AI ethics. An Asia Strategy on AI that considers ethical AI within commercial, people-to-people, and foreign policy agenda would certainly enhance Canada’s ability to achieve its policy goals on all these fronts.

[1] The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, 2019 National Opinion Poll: Canadian View on Human Capital from Asia. (Forthcoming)

[2] APF Canada, 2019 National Opinion Poll. (Forthcoming)

[3] Canadian Bureau for International Education, “Another record year for Canadian international education,” Canadian Bureau for International Education, https://cbie.ca/another-record-year-for-canadian-international-education/ (February 15, 2019).

[4] Alex Usher, “Canada’s growing reliance on international students,” Policy Options, https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/august-2018/canadas-growing-reliance-on-international-students/ (August 29, 2018).

[5] Remco Zwetsloot, Strengthening the U.S. AI Workforce (Washington, D.C.: Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 2019).

[6] Zachary Spicer, Nathan Olmstead, and Nicole Goodman, Reversing the Brain Drain: Where is Canadian STEM talent going? (Toronto: Brock University, 2018).

[7] Future of Humanity Institute, The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation (Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute, 2018).

[8] High-level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI (Brussels: European Commission, 2019).

[9] Will Knight, “One of the fathers of AI is worried about its future,” Technology Review, https://www.technologyreview.com/s/612434/one-of-the-fathers-of-ai-is-worried-about-its-future/ (November 17, 2018).

AI & Geopolitics

Not a Trade War, But a Tech War

Technology accentuates the existing geopolitical tension between China and the U.S. Craig Allen, the President of the U.S.-China Business Council argued, “the trade part is incidental: it’s a technology war, not a trade war.”[1] And AI is central here.

AI could well become a theatre where geopolitical tensions might materialize. The potential capacity and omnipresence of AI has prompted stakeholders in Europe and North America to emphasize ‘liberal’ aspects in discussions about AI ethics and governance. For instance, the ‘Montreal Declaration for Responsible AI’ highlights the importance of “democratic participation” and “diversity inclusion.”[2] Much of the public discussion about AI in the West touches upon concerns over AI’s negative impact on civil rights and democratic institutions – accentuating the differences between and fears towards China. For example, Beijing’s use of AI for citizen surveillance and the development of advanced AI-run weapons has furthered already existing fears towards China in the West.

The politicization of AI in this context raises a serious risk for global governance. In February 2019, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the launch of the national AI Initiative, which articulates an intent to engage in “international outreach” that maintains “American values and interests,” which inherently excludes China. At the same time, China continues its engagement with developing and developed countries through its Belt and Road Initiative, which includes a significant digital component that will allow Beijing to influence norms and standards within this growing sphere of influence.

The social, economic, and political aspect of data, combined with the increasing omnipresence and capacity of AI, requires global conversations on ethics, standardization, and governance – as illustrated in the threat that autonomous weapons pose to humanity. However, the politicization of AI along existing geopolitical fault lines might hinder this much-needed collaboration on AI governance among states.

In this context, the Government of Canada must understand that technology can no longer be decoupled from its foreign affairs – especially vis-à-vis the U.S. and China – and that it must strategize accordingly. Geopolitics in the 21st century is likely to be marked by a further divergence between the world’s two superpowers. Canada will be able to exercise more agency not as a party to one block or the other, but as a ‘middle power’ that convenes and facilitates key discussions with other like-minded middle powers. AI governance is a particular area where Ottawa could play such a role. The federal government’s role here is crucial, but it must also complement – and be complemented by – efforts in commercial and people-to-people engagement, which will add further weight on Canada’s international efforts on AI governance. This, again, reinforces the importance of developing a comprehensive Asia Strategy on AI.

[1] Noa Ronkin, “U.S.-China Trade Dispute Likely to Morph into Technology War, Says President of the U.S.-China Business Council,” Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, https://fsi.stanford.edu/news/us-china-trade-dispute-likely-morph-technology-war-says-president-us-china-business-council (March 18, 2019).

[2] Université de Montréal, Montreal Declaration for a Responsible Development of AI (Montreal: Univesité de Montréal, 2019), https://www.montrealdeclaration-responsibleai.com/the-declaration.

Conclusion

What Should Canada Do?

Canada has been caught in the middle of the current geopolitical crossfire in the fight between the U.S. and China, as illustrated by the deterioration of Ottawas’ relations with Beijing following the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou on a U.S. extradition request. Canada will be increasingly pressured by the U.S. and China to pick sides in this standoff, with implications for businesses. Canada’s AI – especially as Canada continues to remain a favourite destination for global companies – faces the risk of becoming a future theatre of conflict between China and the U.S., as both superpowers see themselves engaged in an ‘AI race’ to gain supremacy over this technology. As such, Canada’s decisions on talent attraction, research collaboration, and investment deals featuring AI – especially those involving China – will increasingly be influenced by competition between Beijing and Washington. In other words, the geopolitical gets intertwined with business in this context, and this risk requires a more strategic approach.

As such, the technological is now geopolitical, with impacts on commercial and people-to-people engagement. It is now urgent that the Government of Canada work on an Asia Strategy on AI that considers all of these aspects as it navigates this new geopolitical chessboard. The Strategy should address AI at three different levels (trade and investment, people-to-people engagement, and geopolitics) with a long view, all mutually supporting each other, and accounting for the nature of the technology and Canada’s place in the world today. Strengthened trade and investment and people-to-people ties will provide a stronger leverage point for the Government of Canada to become a more effective player when engaging with other states on regulating the role of AI in the world.

Further, AI is an opportunity for Canada to become a leader and embed its ‘progressive values’ in global governance. Leveraging its identity as a ‘middle power’ and its array of star researchers such as Bengio and Hinton, whose voices carry weight, Canada could lead by convening international players to set positive norms and standards on AI. Again, Asia is key; countries in Asia – South Korea, Japan, and Singapore, for instance – must navigate that fine line between China and the U.S. Canada has a window of opportunity to work closely with these states to collaborate on international governance of AI. In the global south, Canada could be more present by approaching AI as a development policy issue – collaborating with state and non-state organizations to help them gain increased access to AI technologies, and at the same time promoting ‘ethical' or ‘responsible’ uses of AI. The entry through AI as development would also provide long-term commercial opportunities in what will become the world’s largest markets by the mid-21st century. The emergence – and rapid proliferation – of AI places Canada at a unique crossroads, both exposing it to threats and presenting it with new opportunities, especially in Asia. Clearly, the time for an Asia Strategy on AI is now.

Recommendations

The Government of Canada should work with Canadian AI stakeholders to develop a coherent Asia Strategy on AI that co-ordinates activities in trade and investment, people-to-people engagement, and geopolitics. Such a Strategy should be comprehensive and dynamic, and the following recommendations are not meant to be exhaustive, but rather to provide starting points for Canada’s Asia Strategy on AI:

- Continue to support investment attraction from Asia to Canada, but also look beyond conglomerates and explore creative ways of working with small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Large conglomerates in advanced Asian economies will continue to seek access to Canadian AI talent, and this is an opportunity that should be pursued. At the same time, it would be worthwhile to pursue creative ways of enabling investment and/or R&D collaboration with SMEs that are currently deterred by cost and language barriers, but are nonetheless poised to drive the region’s economic growth in the next few decades.

- Leverage Canada’s world-class AI research to attract, train, and retain talent with a focus on Asia. Talent is the greatest asset in the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Canada should leverage its world-class researchers and institutes to attract the best and the brightest in AI, especially as the U.S. continues to limit access to foreign talent. At the same time, Canada should pursue ways of retaining AI talent in Canada, but also consider the role of outbound talent as potential purveyors of Canadian research ethics and as connectors in commercial sectors abroad.

- Leverage excellence in research and commercial ties to promote ethical uses of AI in practice, especially in developing countries. Developing countries in South and Southeast Asia regard AI as a key technology that will contribute to their economic and social development agendas. However, these states are limited by a lack of digital infrastructure and talent, and development-oriented use of AI may create risks of unethical uses of the technology. In this context, Canada should integrate AI into its development policy agenda, supporting AI deployment and promotion of its responsible uses.

- Play an increased role and facilitate discussions on AI governance amid the ‘new Cold War’ in multilateral settings. As tension continues to rise around technology and geopolitical fractures, Canada should continue to embrace its identity and role as a responsible ‘middle power’ to facilitate key conversations between disagreeing parties and lead the drive for global governance of AI. Especially in the context of China and the U.S., Canada’s technological expertise and ‘middle power’ role on the international stage position Ottawa to facilitate constructive discussions on global AI governance.