The Takeaway

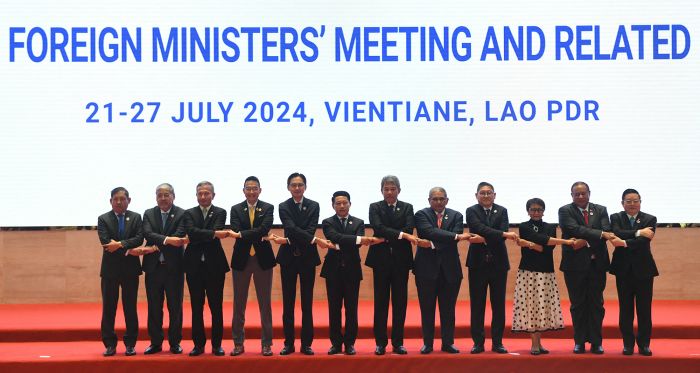

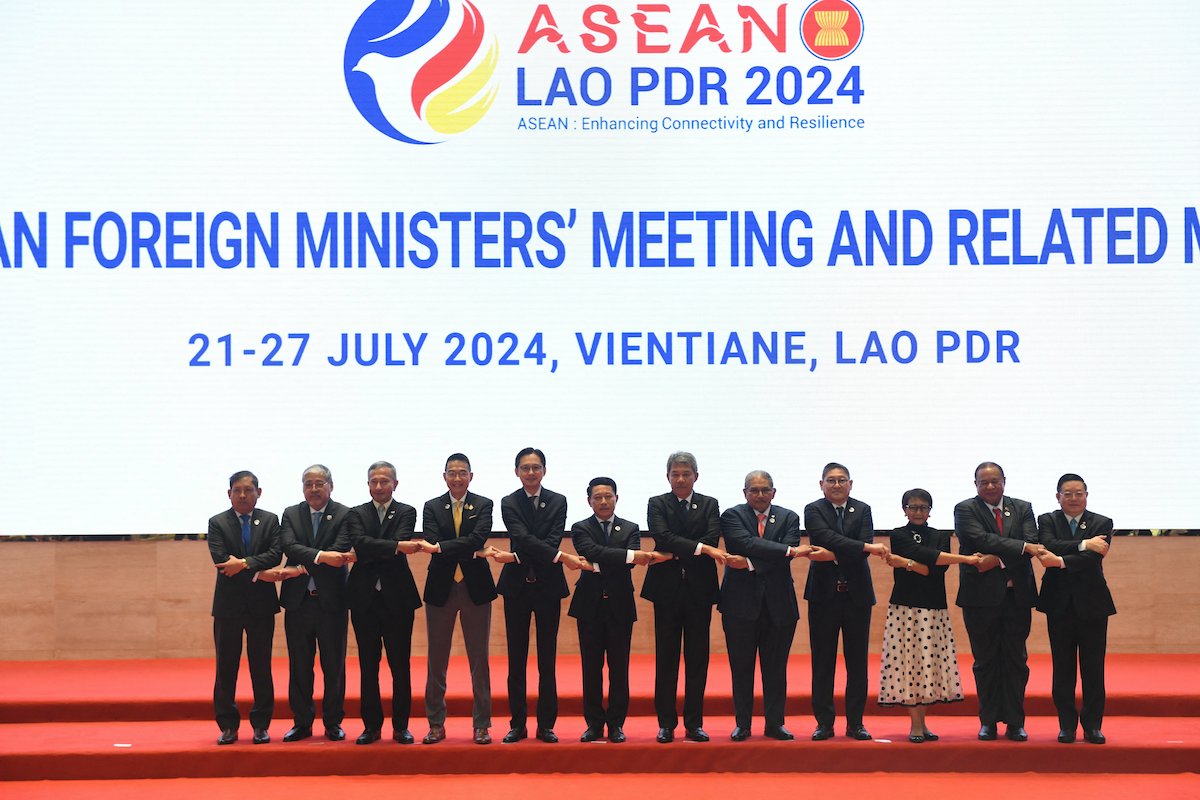

The 57th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (AMM), held in Laos on July 25, indicated that the bloc remains as divided as ever over how to respond to the two most significant threats to regional peace and stability: the worsening crisis in Myanmar and rising tensions in the South China Sea.

This lack of unity could further undermine the bloc’s ability to promote ASEAN centrality –the belief that ASEAN should be the primary channel for tackling regional issues and interacting with external powers. In the context of growing great power competition and rivalry, a further erosion of ASEAN centrality could also open the door for external actors to exert more influence over the region.

In Brief

- From July 24 to 27, ASEAN held a series of high-level dialogues in Vientiane, Laos, which were attended by the foreign ministers of ASEAN member states as well as ASEAN’s Dialogue Partners – Australia, Canada, China, the E.U., Japan, New Zealand, Russia, South Korea, and the U.S.

- Discussions about the civil war in Myanmar – an ASEAN member – took place against the backdrop of its military becoming less restrained in the use of force against civilians. Since the junta overthrew the democratically elected government in 2021, ASEAN has clung to a Five-Point Consensus plan that calls for an immediate cessation of violence and inclusive peace talks. The junta has done little more than pay lip service to that plan. While Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore have grown more vocal in their criticism of Myanmar’s military, other ASEAN members, such as Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, have advocated for a “softer” approach of engaging bilaterally with the junta.

- ASEAN members also remain divided over how to address Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, especially against the Philippines and Vietnam. For more than two decades, China and ASEAN have been working on a South China Sea Code of Conduct (COC) – a set of guidelines to lessen tensions by defining rules and responsibilities for relevant states. While the Philippines and Vietnam have said the COC should be legally binding, non-claimant states within ASEAN, such as Cambodia and Laos, remain hesitant for fear of provoking China, given its considerable economic influence. Negotiations to finalize the COC are scheduled to conclude in 2026.

- Russia and China, in addition to holding a trilateral meeting with Laos, also met bilaterally at the sidelines of the ASEAN meetings, pledging to support ASEAN centrality and deepen co-operation to counter interference from extra-regional actors – a thinly veiled reference to the U.S.

- Canadian Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly attended the ASEAN-Canada Post-Ministerial Conference on July 26, reaffirming the ASEAN-Canada Strategic Partnership launched in 2023, and agreed to jointly develop a Plan of Action to steer the Partnership. The meeting focused on the crisis in Myanmar, clashes in the East and South China Seas, and North Korea’s illegal weapons development programs.

Implications

ASEAN’s Myanmar approach remains inept as the crisis worsens. Disagreement within ASEAN over how to engage with Myanmar’s evolving conflict has weakened the bloc’s negotiating power and its ability to exert pressure on the junta. This ineffectiveness has been noticed within Myanmar: the proportion of respondents in the country who believe that the Five-Point Consensus plan will not “work with the intransigence of the military” rose from 16.5 per cent in 2023 to 41.8 per cent in 2024.

Disunity on South China Sea leaves some members seeking assurance beyond ASEAN. ASEAN member states are similarly divided over how to respond to China increasingly pressing its South China Sea claims against four ASEAN members: Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. In particular, Laos and Cambodia, during the recent ASEAN Post-Ministerial Conference with China, refused to include a reference in the meeting’s joint communique condemning a Chinese Coast Guard vessel’s recent collision with a Filipino resupply ship.

Fragmentation within ASEAN could further weaken its negotiating power, enabling China to drive a deeper wedge within the bloc by undermining collective action and negotiating bilaterally with member states. A fragmented ASEAN could also make it challenging for a consolidated response by other actors, like Canada, that see China’s actions in the South China Sea as a violation of international law.

What’s next

1. Extra-regional actors seek a stronger foothold in ASEAN. The decision by China and Russia to strengthen their ties with the region is seen as a counter-balancing move to weaken the West’s growing influence in Southeast Asia and is compounded by ASEAN’s disunity. Both countries also wield considerable sway in Myanmar. Beijing has an outsized economic and political influence, and Moscow has close military ties with the junta. Their intervention in Myanmar, which skews towards support for the military, could help prolong military control and undermine the pro-democracy resistance forces.

In the South China Sea, China and Russia have been holding joint naval exercises, strengthening bilateral military ties. To counter China’s aggressions, the Philippines has looked to other allies and deepened its military ties with the U.S., Australia, and Canada.

2. Malaysia will take the helm in 2025. When Malaysia assumes the ASEAN chair in January, it could try to shift ASEAN’s approach to both issues. Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim has expressed his intention to steer the bloc towards a more unified and assertive role in addressing regional tensions, including a more proactive approach on Myanmar that would include engaging with the country’s relevant stakeholders, and not just the military. However, Kuala Lumpur’s emphasis on prioritizing ASEAN’s economic role and trade relationships, along with its decision to join the BRICS group, may nudge it toward continuing to take a lenient approach to Beijing’s claims in the South China Sea.

• Edited by Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager and Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, APF Canada.