The Takeaway

India’s passing of the Women’s Reservation Bill, intended to reserve one-third of national and state legislative seats for women candidates, has been hailed as a move forward for women’s representation throughout the country. However, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) says the bill’s implementation will follow a national census and subsequent delimitation exercise, or electoral boundary redistribution, tentatively planned for 2026. These obstacles could delay implementation of the bill, which also excludes reservations for women from certain disadvantaged groups. The Indian government must address these issues, as well as other economic and social barriers faced by women in India, to truly improve women’s representation in politics.

In Brief

- On September 28, the Lok Sabha, the lower house of India’s parliament, passed the Constitution (128th Amendment) Bill, or the Women's Reservation Bill (Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam), and its six clauses.

- The bill, signed the same day by Indian President Droupadi Murmu, mandates that one-third of the seats in the national Lok Sabha and Delhi Legislative Assembly, and state legislative assemblies throughout India, be reserved for women candidates.

Implications

- Trends in women’s involvement in Indian politics

Political representation among women in India currently ranks 141st out of 185 countries globally, with women holding 15.2 per cent of seats in the Lok Sabha and 13.9 per cent in the Rajya Sabha (upper house) as of 2023. Six previous attempts at a women’s reservation bill were unsuccessfully waged between 1996 and 2008. These failures were largely due to opposition from regional parties, along with demands for additional inclusion of women from disadvantaged class groups — an issue that has been raised with the current bill.

- Demands for sub-quotas for women from OBCs, minorities

While the current Women’s Reservation Bill orders that one-third of seats reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes be reserved for women within these communities, critics have pointed out that the bill excludes sub-quotas for so-called Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Economically Backward Classes (EBCs), which are categorized based on specific criteria of social and economic disadvantages. These class groups are categorized as distinct from Scheduled Castes and Tribes based on specific educational and social disadvantages. The bill also makes no mention of women’s inclusion within Union Territories, such as Jammu and Kashmir.

- Bill’s dependence on delimitation exercise and possible delays

Another criticism of the Women’s Reservation Bill is the census and subsequent delimitation exercise that the BJP says must be carried out before the bill comes into effect. India’s once-a-decade census has been indefinitely delayed since the COVID-19 pandemic. The information from this fresh census would provide the data needed to carry out a new delimitation exercise. Such an exercise would see boundaries of territorial constituencies redrawn and seat allocations readjusted to correspond with population numbers to ensure balanced political representation. The exercise has been delayed until at least 2026 — or even later, depending on the timeline of the completed national census. Opposition parties have criticized the central government for linking the Women’s Reservation Bill to delimitation, as the combined census and delimitation processes may take years to implement.

What's Next

1. Impacts on 2024 Indian general elections

Because of its connection to the delimitation process, the Women’s Reservation Bill will not come into effect before the 2024 Indian general elections. However, the bill has become a major political tool ahead of the elections. The BJP’s passing of the bill after years of delay is seen by opposition parties as a move to secure more votes from women without actually delivering on the bill itself. In response, the president of the opposition Indian National Congress stated that if Congress comes to power in 2024, his party will implement the bill immediately and amend it to include reservations for OBCs.

2. Barriers against women’s political participation

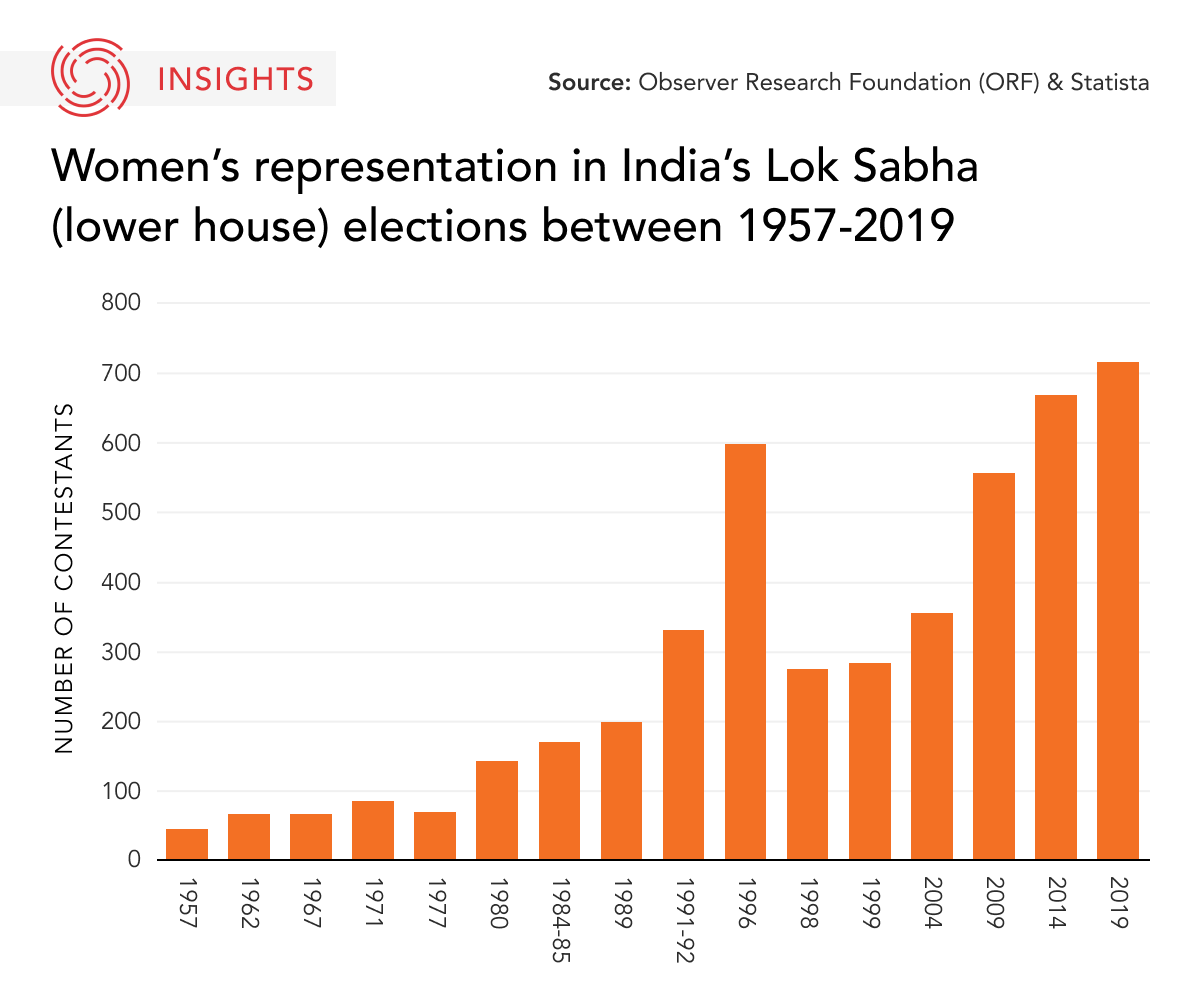

While the Women’s Reservation Bill represents a move forward in encouraging women’s political participation, there are several other social and economic barriers that still need to be addressed. According to a study by Delhi-based think-tank Observer Research Foundation, the number of women candidates in India’s Lok Sabha elections has steadily increased since 1998, largely due to reservations introduced at lower constituency levels. However, women made up less than 10 per cent of candidates during the 2019 general elections. The most common barriers to women’s political participation include patriarchal taboos and gendered social norms that discourage women’s involvement in decision-making processes, insignificant financial resources needed to run for candidacy, lower literacy levels, and a lack of access to political education.

3. Impacts of gender quotas in other countries

As of 2023, 137 countries globally have implemented some form of gender quotas in legislative bodies. These quotas have often resulted in positive policy changes. Some results of improved gender representation in politics include a rise in government expenditures towards public health in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa, the passing of new legislation around women’s rights in Argentina, and increased investments in public goods such as clean drinking water and road infrastructure through Indian village councils. However, these changes often take years to come into effect due to existing social norms in many countries. This may also be the case with India’s Women’s Reservation Bill, considering its possible delays in implementation.

• Produced by CAST’s South Asia team: Prerana Das (Analyst); Suyesha Dutta (Analyst); and Deeplina Banerjee (Analyst).