On May 3, China launched its “complex and ambitious” Chang’e-6 space mission, which, if successful, will be the first ever to collect samples from the far side of the moon. This mission, and other future “firsts” on the moon, Mars, and beyond are bolstering China’s plans to become a space superpower by 2045. There are already ample signs that China is enacting policies and making the necessary investments to do so. In April, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the most extensive reorganization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in a decade, with an emphasis on strengthening China’s military presence in space. And in its 2022 white paper, Beijing outlined a range of space policies focused on defending China’s national security, incentivizing its commercial space industry, boosting innovation, and making advancements in ventures such as satellite services, space tourism, and resource extraction.

The steep increase in its expenditures on space is another clear indication of China’s ambitions: these expenditures mushroomed from C$3 billion in 2022 to C$19.5 billion in 2023. Although still trailing behind the U.S., which spent an estimated C$100 billion in 2023, China’s investments are showing results not only in its state-led programs but also in its commercial program, which is driving advances in technology, including spacecraft design, propulsion systems, and robotics.

But China’s role in the rapidly evolving and expanding global space landscape is causing trepidation among some other spacefaring actors. Specifically, Beijing’s space program is part of the broader realm of U.S.-China competition, with clear diplomatic, military, and economic dimensions, including concerns about China’s counter-space weapons, cybersecurity threats, and potential to exploit lunar resources. Part of this competition involves forming partnerships with other established and emerging space actors, including Canada. Whether the U.S., China, and others can find ways to work together in space while trying to manage tensions in their relationships on Earth remains to be seen.

History and milestones in China’s space program

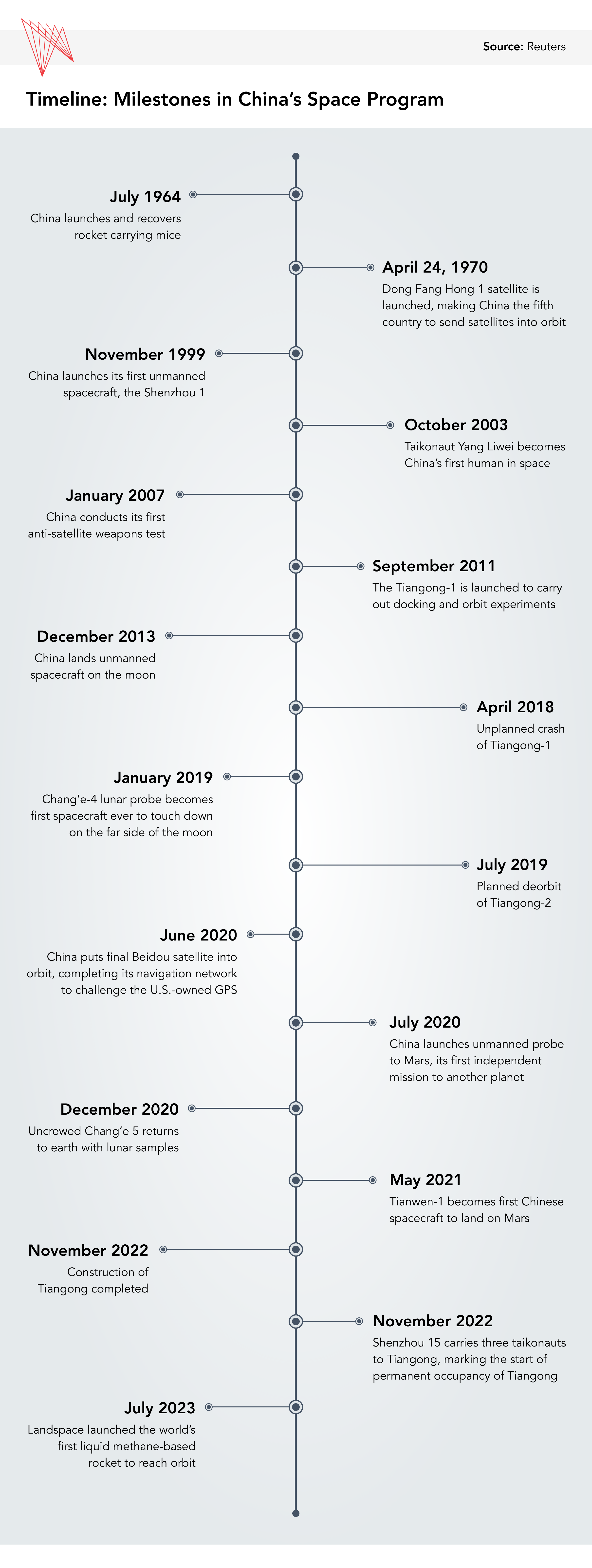

China’s path to becoming a space power is six decades in the making, beginning with its 1964 rocket launch and recovery. Six years later, in 1970, it became only the fifth country (after the Soviet Union, the U.S., France, and Japan) to indigenously launch – that is, without relying on launch capacities from other space powers – an artificial satellite, the Dong Fang Hong 1. In the 1980s, under then-leader Deng Xiaoping, China’s space program became more structured and was guided by a science and technology development program called Project 863. This initiative formed the foundation for the pivotal Project 921, also known as the China Manned Space Program, which, in 1992, articulated the country’s objectives of sending astronauts (also known as ‘taikonauts’) to space and constructing an orbital space station. In 1993, Beijing established the country’s national space agency, the China National Space Administration (CNSA). This institutional support helped China launch its first unmanned spacecraft in 1999 and send its first taikonaut into space in 2003.

In 2019, after several years of progress (see timeline below), China’s space program began to meet other impressive milestones. That year, it became the first country to land on the far side of the moon. In 2020, its Tianwen-1 mission landed its first rover on Mars. And by late 2022, China completed the construction of the Tiangong Space Station, with plans already underway for further expansion. Those plans will soon pay dividends: the International Space Station is scheduled to be decommissioned in 2031, and when that happens, the Tiangong will be the only station in orbit. In the meantime, by the end of the current decade, China plans to put astronauts on the moon; explore the outer solar system; and, through its Tianwen-4 mission scheduled to launch in 2029, explore one of Jupiter’s 95 moons (Callisto) and conduct a flyby of Uranus.

China’s commercial space sector

In addition to monitoring the implications of the accomplishments described above, China’s partners and competitors are also keeping an eye on the growth of its commercial space sector. In 2023, 17 of China’s 67 rocket launches were carried out by commercial space actors. In July 2023, LandSpace, one of China’s first commercial space companies, launched a methane-liquid oxygen space rocket, the first of its kind.In 2024, the company’s site on Hainan Island will conduct its inaugural launch of the rocket. In early 2023, two other Chinese companies – Hong Kong Aerospace Technology Group and Touchroad – signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) valued at more than C$1.3 billion with the government of Djibouti to build China’s first overseas spaceport in that country. (Djibouti is also home to China’s only overseas naval base.) As part of the MOU, the spaceport will be completed by 2027 and co-managed for 30 years before being transferred to the Djibouti government.

However, given the role of state-owned enterprises in China’s commercial sector, the line demarcating public from private space enterprise is blurry, making it challenging to ascertain the magnitude of the latter. One example is the state-owned China Satellite Network Group. Mirroring U.S.-based SpaceX’s Starlink, this company plans to launch up to 26,000 satellite components of an internet constellation globally between 2024 and 2029.

The public and private sectors are also entwined in China’s space-related infrastructure projects, including the space component of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Also referred to as its “Space Silk Road,” this initiative includes satellites, navigation, and location positioning. China’s BeiDou satellite navigation system, an alternative to GPS, has 45 satellites in orbit and 120 ground stations and is meant to be the “digital glue” for China’s BRI infrastructure projects extending from East Africa to the South Pacific. This CNSA-led navigation system was initially developed for military purposes, but is now operated in partnership with private entities and other foreign governments for civilian use. It is the world’s largest of its kind, and has achieved a level of precision that has caused concerns in the U.S. and the U.K., with London raising questions about BeiDou’s potential to limit the U.K.’s access to space and to allow China to conduct surveillance of British citizens. Many of Beijing’s BRI partners, however, are not deterred and are increasingly interested in accessing BeiDou’s services for everything from civilian navigation to missile tracking.

At the subnational level, Chinese cities and provinces are other players in China’s space sector. The Beijing municipal government’s five-year action plan, which commences this year, aims to foster local and international innovation to nurture startups and other high-tech private entities in the space sector. In 2023, the Shanghai government also released an action plan for its commercial space sector, and the province of Shandong has articulated similar goals for 2030 and 2035.

China’s role in global space governance and its expanding international partnerships

This increasingly dense web of state and private space actors will figure into the role China will play at the international level. Among the ambitions articulated in Beijing’s 2022 white paper is the desire for the country to become a leader in developing a more robust international framework for space governance through its active participation in international rule-making and the formulation of its own national space law. Over the past eight years, China has signed at least 46 agreements with 19 countries and four international organizations to promote global space co-operation. In 2016, China signed an MOU with the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) to extend the use of Tiangong to all UN member states. In April 2024, the director of UNOOSA commended China’s collaborative efforts on the Tiangong Space Station, referring to these efforts as a benefit to all humankind.

This type of international collaboration has earned Beijing considerable diplomatic goodwill. For example, working with UNOOSA, China collaborates with newer space actors like Saudi Arabia to conduct experiments in space from Tiangong. It has also welcomed other Gulf Cooperation Council countries to participate in joint missions aboard its space station and “financed, built, and launched” satellites for countries with which it has close relationships – including Laos and Pakistan – as part of a delivery-in-orbit contract whereby China both sells and launches satellites on their behalf. This arrangement allows China to compete in a market that has long been dominated by the U.S.

China has also partnered closely with Russia, a major, albeit declining, space power. The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) is a China-Russia joint initiative to construct a base on the south pole of the moon. The plan is that by 2050, the ILRS will be fully operational for lunar research and its lunar launch pads will support crewed interplanetary missions. Ten countries have signed on to participate in the ILRS: Azerbaijan, Belarus, China, Egypt, Pakistan, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey, and Venezuela.

This growing partnership around the ILRS is seen as a competitor to the U.S.-led Artemis Accords. These non-binding Accords reinforce the provisions in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty based on the U.S.’s interpretations of resource extraction permitted under the treaty. Thirty-nine states have signed on to the Accords, including India and several close U.S. allies, including Canada and South Korea. However, some of these same countries – France, Germany, India, and Japan – have also joined China on projects related to the final module of its Tiangong space station.

Growing China-U.S. competition in emerging space race

A notable exception to China’s expanding list of space-related partners is the United States. China is not part of several key international partnerships, such as on the International Space Station and Artemis missions, primarily because of Washington’s objections. The U.S. Congress, under the Wolf Amendment (2011), prohibits NASA from using federal funds to engage bilaterally with China on space co-operation. In addition, as part of its International Traffic in Arms Regulations, the U.S. also restricts the export of satellite parts to China if it believes such exports could pose a military threat.

During a recent U.S. congressional hearing, the head of NASA, Bill Nelson, stated that China’s “civilian space program is a military program.” And in its 2023 report, the United States’ Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) described China’s space sector as a threat to U.S. security. It highlighted the nation’s aspiration to outcompete the U.S. by 2045, which could “erode U.S. influence across military, technology, economic, and diplomatic spheres.” Its primary concern – and one of the factors that motivated the congressional ban – is the role played by the PLA in areas such as navigation and satellite reconnaissance. Of the more than 700 satellites China has placed in orbit, 245 are for military purposes. (In comparison, India has only 26 military satellites out of more than 120.) Meanwhile, ground stations, aside from satellite tracking and communication, can be used to infringe on personal privacy, jam satellites, and track foreign surveillance assets and missile launches.

Washington’s allies have also cancelled contracts with China over security concerns. In 2020, the Swedish Space Corporation (SSC) decided not to renew contracts for a Chinese ground station in Kiruna, Sweden, due to concerns that the data gathered at the station could be used for military intelligence, which would violate the SSC’s terms of use. That same year, the SSC decided not to renew other contracts with China at ground stations in Australia and Chile. Space collaboration between CNSA and the European Space Agency (ESA) has also been impacted by these concerns; European astronauts were expected to visit Tiangong by 2022, but these plans were suspended by the ESA, even though the CNSA and ESA previously collaborated on multiple fronts, including on lunar and deep space exploration. ESA director Josef Aschbacher gave a lack of “budgetary and political” approvals as the reason for the halt on collaboration with China. The ESA’s 22 member states will instead focus on the International Space Station. The International Space Station was constructed and is maintained by five space agencies: the ESA, NASA, the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and Roscosmos (from Russia).

Canada, an Artemis partner and International Space Station member, is also absent from China’s growing network of collaboration. Ottawa has concerns over Chinese interference in the Canadian space sector. In 2021, a CSA engineer was accused of acting as a middleman for Chinese firm Spacety. Though acquitted of breach of trust, the engineer still faces disciplinary measures. In addition, in January 2024, the Canadian government released a list of sensitive research areas and institutions, including some in China, that could pose a risk to Canada’s national security. Among those on the list are the North China Institute of Aerospace Engineering and China’s Space Engineering University. Canadian researchers working in these sensitive research areas may be unable to access federal grants without certifying that they are not working with or receiving funds from these or other institutions on the list – potentially impacting collaborative research efforts.

The perils and pitfalls of unmanaged competition

While competition in space may be unavoidable, how that competition unfolds can still be managed. Unmanaged competition carries profound risks, such as the threat to infrastructure – and the planet below – in Earth’s increasingly overcrowded orbit. In 2022, for instance, two SpaceX Starlink satellites nearly collided with the crewed Tiangong, with the latter having to take emergency measures. China submitted a diplomatic note to the UN notifying it of the near collision. Given that nearly half of the objects in Earth’s orbit belong to the U.S. and its private entities, and the growing risk of collision with China’s satellites, constructive and open dialogue between the two countries is necessary to ensure the safety of Earth’s near orbit.

For now, the U.S. and its allies and China are caught in a security dilemma in space – where each side is building up its military defences in response to the uncertainty over the other’s activities. But operating in an environment as “cold, dark, and dangerous” as space makes collaboration almost a necessity given the sheer costs and risks involved.

A narrow window of opportunity for collaboration

Beijing has expressed its willingness to collaborate with the U.S. despite the latter’s security concerns. The China National Space Administration has repeatedly referenced the Wolf Amendment as an obstacle to potential co-operation with the U.S. in space. For NASA to work with China’s CNSA, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation must certify that there is no risk of technology transfer or violations of human rights in any collaborative endeavour. In fact, in a rare move, in December 2023, NASA provided the U.S. Congress with such a certification to obtain lunar samples acquired by China’s Chang’e-5 for research purposes. The Chang’e-5 lunar samples, estimated to be approximately two billion years old, are expected to give scientists unique insights into the origins and composition of the moon. China has extended an invitation to researchers globally to access samples for research purposes, an action China states is in line with its aim of exploring and developing space peacefully while engaging in international co-operation.

International co-operation in space, a global commons, not only reduces the costs and risks for participating nations but can also deliver “diplomatic utility,” particularly where co-operation has not been the norm. The U.S. and Russia/Soviet Union have co-operated on multiple space efforts, including the Cold War-era Apollo-Soyuz project for testing an international space rescue, with a successful drill completed in 1975. Despite tensions over Russia’s war in Ukraine, Russia and the U.S. continue to work together on the International Space Station. In March, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket transported three American astronauts and one Russian cosmonaut to the International Space Station as part of the six-month-long Crew-8 mission that will conduct more than 200 scientific experiments.

This U.S. and Russia/Soviet Union co-operation, which was necessary and yielded numerous benefits, offers a model for potential U.S.-China co-operation. Such a model of collaboration with China will have to consider the current state of technology that comes with greater military and cybersecurity security threats. But the two countries could work on co-operating in areas of lower military threat, such as deep space exploration.

What’s next for China’s celestial ambitions?

China’s impressive technological achievements and future ambitions in space are being bolstered by its growing influence and attempts at showing leadership in international co-operation. Beijing’s national space program and its booming commercial space industry are propelling the country to the head of the pack of the world’s major spacefaring nations.

While it spearheads its own national space program, China is also keen to create a reputation as a collaborative state that upholds the international rules-based order in space. The U.S. and its allies are skeptical of this, and a new space race remains a real possibility – with some saying it is already on.

• Editors: Vina Nadjibulla, Vice-President Research & Strategy, APF Canada; Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager, Asia Competencies, APF Canada.

Also in this series: For an overview of global and Asian space programs, please see the introduction to this series. Our next report will focus on India, followed by additional reports on Japan, South Korea, and Canada.