The Takeaway

With its population shrinking by 850,000 in 2022, China finds itself at a turning point in its escalating demographic crisis. Birthrates have hit record lows year after year, compounded by pessimism in China’s economy and the social upheavals brought on by its COVID-19 management. As central and local authorities rush to provide birth subsidies, many young Chinese say structural ills in society deter them from having children.

In Brief

China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced at a press conference on January 17, 2023, that, as of 2022, the country‘s population stood at 1,411,750,000. This marks the first time that China’s population has shrunk since 1961. In all likelihood, China’s population has reached its peak significantly earlier than many demographers had expected.

The country’s population structure has become concerning to citizens and policymakers alike. China’s working-age population decreased by 6.66 million between 2021 and 2022, while the number of people above the age of 60 grew by 12.68 million. Experts expect an even stronger surge in the number of elderly citizens over the next two decades, as “baby boomers,” born post-famine in the 1960s, enter retirement.

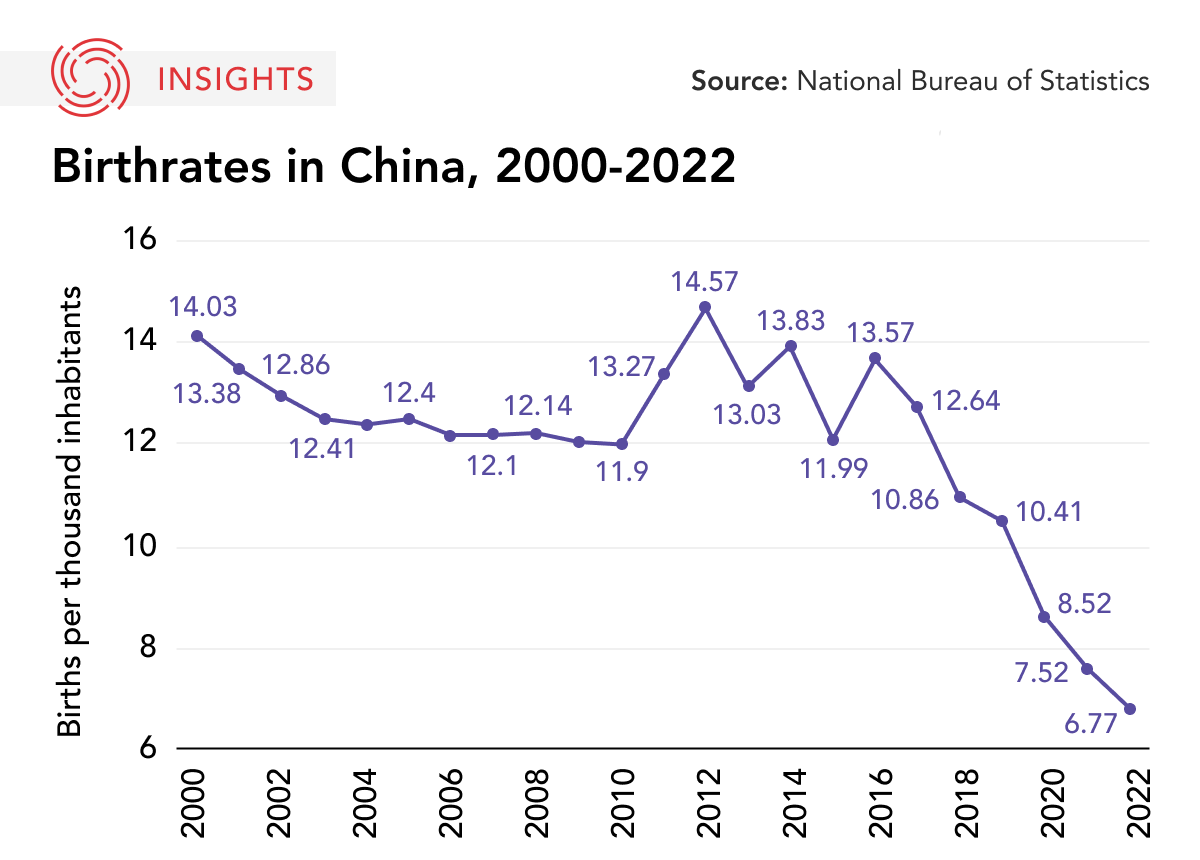

China’s 2022 birthrate was 6.77 births per 1,000 people, a 10 per cent decrease from 7.52 births per 1,000 people in 2021. Su Yue, principal economist for China at the Economist Intelligence Unit, told the BBC that COVID-19 and the ensuing lockdowns likely drove down birthrates. She expects the slump to continue, if not worsen, after reopening, as delays in marrying and childbearing accompany persistently high unemployment and stagnant wages.

Implications

Since the introduction of the three-child policy in 2021, authorities at both central and local levels have launched multiple “birth-encouraging” initiatives. The national health authority issued in August 2022 a multi-department joint plan to offer systemic support for marriage, childbirth, child-rearing, housing, taxation, and education, including subsidies for assisted reproductive technology. Throughout 2022, many provincial and city governments came out with local versions of child subsidies and expanded maternity leave benefits. Most recently, south China’s metropolis Shenzhen announced a C$195-million (974 million-yuan) subsidy program for parents giving birth to their first, second, and third child. Around 40 cities wrote specific aids to multi-child families into their housing documents in the second half of 2022.

Yet the high costs of child-rearing continue to deter families from having children. An online survey conducted by China Youth Daily in early 2022 showed that 81.4 per cent of respondents selected “economic pressures” as a major issue preventing them from having children. Demographer Cui Shuyi of the Shandong Academy of Social Sciences told the 21st Century Business Herald that for most Chinese families, what effectively amounts to an extra C$100 (500 yuan) a month at most is unlikely to sway family-planning decisions. With continued uncertainty brought on by the pandemic, difficult economic outlooks, and shocking instances of gender-based violence, a January 2023 Asia Society Policy Institute report asserts that for young Chinese, not having children is "a kind of plebiscite on social conditions."

In a country where there are around 32.4 million more men than women, potential mothers are already in short supply. Over the past decade, a nationwide discourse on gender inequality has highlighted the systemic barriers faced by single mothers, the unjust pressure on women when they enter marriages and give birth, and the workplace discrimination that disadvantages women of childbearing age. Even some of the birthrate-boosting policies implemented by local governments make out-of-wedlock and adopted children ineligible. The government, then, needs to ensure stronger protections for women if it hopes to revive the birthrate. Increasingly opaque institutions, with all-male leadership at the very top, make this a challenging task; as Feng Yuan, a veteran feminist activist, puts it to U.K.-based Financial Times, “the government knows it has to be better to women; yet it doesn’t listen to them.”

What's Next

- Local birth subsidy programs receive wider scrutiny

By 2023, some local birth subsidy programs will have been in place for at least a year. As local governments scramble to manage finances after three costly years of zero-COVID implementation, they may come to view such subsidies with a more critical eye.

- Policymaking and public debate during ‘Two Sessions’

The annual ‘Two Sessions,’ which will see the National People’s Congress and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference convene in March 2023, is always a time for public discourse on domestic policy. Boosting birthrates is likely to be part of the primary agenda, and delegates’ proposals will shine light on emergent government thinking.

3. Regional divisions leave some provinces behind

In 2021, 13 Chinese provinces saw their populations decrease. Many are “rust-belt” provinces in the northeast or interior: with relatively few opportunities, young people depart for larger cities along the coast. As birthrates decrease nationwide, the deleterious impacts of an imbalanced population structure will first rear their heads within the economies of already-struggling regions, while megacities and coastal hubs enjoy the benefits of internal migration for now.

• Produced by CAST’s Greater China team: Maya Liu (Program Manager) maya.liu@asiapacific.ca; Irene Zhang (Analyst).