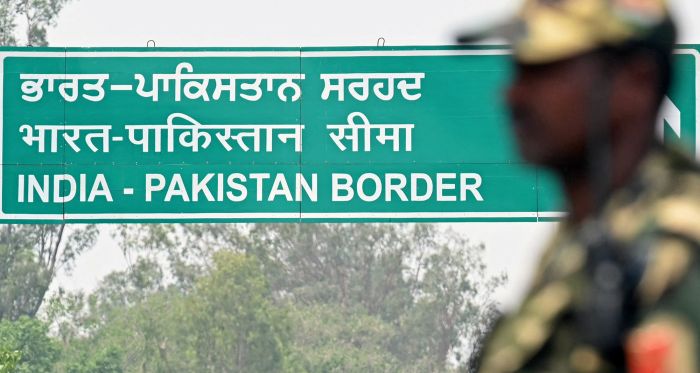

In response to the April 22 terror attack that killed 26 civilians — mostly Hindu tourists — near the town of Pahalgam in India’s Kashmir region, India’s armed forces launched precision strikes on May 7 to dismantle what it considered terrorist bases at nine locations in Pakistan, some deep within the Pakistani heartland. New Delhi alleges that the Pahalgam attackers had ties to Pakistan. (Islamabad denies any links.) As part of Operation Sindoor, India claims to have killed 100 terrorists and destroyed alleged terrorist infrastructure in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Islamabad, however, has asserted that the targets hit by the Indian military were “civilian,” not terrorist, and responded with counterstrikes. This triggered three days of heavy shelling across the Line of Control — the de facto border between the two nuclear-armed neighbours in the contested Kashmir region — as well as missile and drone attacks deep inside each other’s territory, targeting airbases and military infrastructure, with both sides claiming the loss of civilian lives.

While India’s top military officials claim to have secured substantial victories and the threat of further military escalation has abated — at least for now — the longstanding dispute between the two South Asian rivals remains unresolved, and future outbreaks of violence, including terrorist attacks, cannot be ruled out.

The road ahead for India will be paved with dilemmas, including the risk of being drawn into a prolonged military conflict with Pakistan to counter the threat of terrorism. This challenge is further complicated by the suspension of a bilateral water-sharing treaty, ongoing tensions over the Kashmir issue, and the involvement of major powers, particularly China — Islamabad’s close strategic partner and New Delhi’s other regional rival — with which India shares a nearly 4,000-kilometre contested border.

A new security doctrine emerges in India

On May 12, two days after a ceasefire was announced, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi articulated a new doctrine in response to terrorist attacks. According to this doctrine, such attacks would be treated as “acts of war” and would warrant appropriate retaliation, including military action against both the terrorists and the governments allegedly supporting them.

Prior to 2016, India typically refrained from military retaliation in response to terrorist attacks that it believed originated from Pakistan. However, New Delhi increasingly views such attacks as sufficient grounds for a military response, despite the potential threat of nuclear weapons being used in the ensuing conflict. Modi has emphasized that India would no longer be restrained by the threat of “nuclear blackmail.” He reiterated that terror and dialogue cannot go hand in hand, implying that India should not be expected to respond to terrorist strikes by engaging in diplomatic co-operation with the government it believes is backing such attacks.

New Delhi’s frustration with cross-border terrorism reached a tipping point after the deadly Mumbai attacks in November 2008, in which 166 people were killed. These attacks were reportedly perpetrated by terrorists based in Pakistan. While India-Pakistan relations deteriorated sharply after that incident, New Delhi opted not to retaliate militarily.

However, this reluctance to use military force as a punitive response to terrorist attacks began to shift under the Modi administration — first in 2016 and again in 2019, following major terror strikes in India’s Jammu and Kashmir region. In 2016, Indian security forces crossed the Line of Control to carry out precision strikes on alleged terrorist infrastructure in Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Following a suicide bombing in Jammu and Kashmir in 2019 that killed 40 Indian soldiers, Indian forces reached beyond the contested Kashmir region and launched airstrikes in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, targeting an alleged terrorist camp.

The recent Pahalgam attack marked a further escalation. Indian forces struck targets deeper into Pakistani territory than at any point in the last five decades, hitting nine supposed terrorist camps and with significantly more sophisticated firepower and impact. While the strikes were punitive in nature, they also aimed to establish deterrence, sending a message that acts of terrorism would no longer be treated as falling below the threshold for a military response.

This hardening strategic resolve, however, appears to be a double-edged sword for New Delhi. On one hand, it allows the country to cast itself as capable of ensuring its security in a highly tense regional environment where terrorist attacks appear to serve as tactics of proxy warfare. On the other hand, it also heightens the risk of unchecked military escalation between two nuclear-armed neighbours. Critically, this new doctrine implies that with each terrorist attack, New Delhi may feel compelled to deliver a military response — one that could be more serious in scale and intensity than previous instances. Furthermore, dismantling alleged terrorist camps does not guarantee protection against future attacks, calling into question the expectations of deterrence.

Suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty leaves region on edge

Prior to launching Operation Sindoor, New Delhi took other, non-military retaliatory measures against Pakistan. Most prominent was its suspension of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, which governs the sharing of the waters of the Indus River and its tributaries between the two countries. Remarkably, the treaty had withstood two major wars between India and Pakistan, in 1965 and 1971, and multiple skirmishes and smaller-scale conflicts.

Despite reaching a ceasefire on May 10, New Delhi has stated that the treaty remains suspended. With over 80 per cent of Pakistan’s irrigated agriculture and 25 per cent of its GDP dependent on the Indus waters, Islamabad has warned that any attempt by India — the upper riparian state — to divert the water flows would be considered an “act of war.”

In 2023, India sought a “modification” of the treaty, and in 2024 requested a “review,” signalling its intent to revoke and renegotiate the agreement. Under the current framework, India is entitled to about 30 per cent of the Indus waters, while Pakistan receives the remaining 70 per cent. India’s rationale for renegotiation seemingly rests on the demands created by shifting population needs, climate change, the need for clean energy, and its desire to retain strategic leverage in response to cross-border terrorism.

Although the treaty currently limits India’s ability to withhold water by restricting the construction of large storage dams, New Delhi may accelerate the development of new hydropower infrastructure or enhance the storage capacity of existing projects to inflict downstream damage in Pakistan. A recent Reuters report suggests that such developments are already underway, adding to the potential for renewed conflict.

Kashmir remains a flashpoint

The roots of the India-Pakistan rivalry can be traced to competing territorial claims over the Kashmir region since the end of colonial rule in 1947. Both countries claim the entire territory, but an armed conflict in 1948 resulted in the division of Kashmir along the Line of Control, the de facto border, with both sides administering a portion of the contested territory. China administers another section in the east.

This strategically vital and heavily militarized region in the Himalayas has been a persistent flashpoint. Since the 1990s, an insurgency has gripped Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, fuelled in part by cross-border terror networks widely viewed as proxies for the Pakistani state. The territorial dispute flared up in 1999, when Pakistani soldiers crossed the Line of Control. However, the conflict remained limited. A ceasefire agreement along the Line of Control has been in place since 2003, despite frequent incidents along the disputed border.

A turning point came in 2019, when the Modi government revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s semi-autonomous status under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, aiming for the region’s full integration into India. The move lifted restrictions on land ownership and permanent residency, allowing Indians from the rest of the country to settle in the region — prompting concerns about a demographic change in India’s only Muslim-majority territory. Additionally, the region, previously a state within the Indian federation, was downgraded to a Union Territory, placing it under direct central administration from New Delhi. While the revocation of Article 370 was seen by the Indian government as a step toward economic development, and a way to boost tourism and investment, the Pahalgam attack has exposed ongoing security vulnerabilities and the persistent threat of terrorism. Pakistan strongly opposed the 2019 decision, denouncing it as “illegal” and “unilateral,” and responded with measures such as expelling the Indian high commissioner from Islamabad.

The recent Pahalgam terror attack exposed not only the persistent security risks in the region but also its broader implications for regional peace and stability. For New Delhi, a core challenge is that while such security threats may undermine India's focus on economic growth and its positioning as a rising power, its credibility on the world stage ultimately depends on its ability to safeguard itself against external threats.

The great power play in South Asia

Although the U.S. initially signalled that it would take a hands-off approach following the Pahalgam attacks, Washington’s intervention reportedly intensified as the conflict risked escalating into a full-scale war. U.S. President Donald Trump announced what he described as a “U.S.-brokered” ceasefire on May 10. Trump has also stated, “I will work with you both to see if, after a thousand years, a solution can be arrived at, concerning Kashmir.” He also characterized his relations with both countries as “very close.” U.S. Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, also hinted at the possibility of talks on a “broader set of issues” at a “neutral site.”

While India has denied any third-party involvement in securing a pause in the hostilities and ruled out mediation on the Kashmir issue, Trump’s statements may still place New Delhi in a diplomatically awkward position, given its longstanding policy of rejecting external mediation in the Kashmir dispute. This position, rooted in the 1972 Simla Agreement, stipulates that all disputes between India and Pakistan should be resolved “by peaceful means through bilateral negotiations.”

India views Kashmir as an integral part of the country and therefore resists any foreign intervention. This sentiment is further entrenched by India's attempts at internationalizing the issue in the early years at the United Nations, which yielded no substantial diplomatic advantage. Since then, Islamabad’s efforts to raise the issue internationally have only deepened New Delhi’s resistance to external engagement on Kashmir.

Trump's remarks could trigger domestic criticism in India for potentially internationalizing the Kashmir issue once again, and India’s growing strategic closeness with the U.S. could also be perceived as compromising its core position on Kashmir. In recent years, the India-U.S. strategic partnership has been driven in large part by India's emergence as a counterbalance to China’s growing regional assertiveness and has resulted in increasingly close defence and technology co-operation. The U.S. has also become India’s largest trading partner.

In contrast, the recent tensions with Pakistan have exposed fissures in India’s traditionally strong ties with Russia. Moscow’s calls for “restraint” were seen in Indian strategic circles as falling short of the support they expected. Russia’s increasing alignment with China, especially amid its protracted war in Ukraine, is also a strategic irritant.

Finally, the India-Pakistan conflict has highlighted the deepening military and strategic co-operation between Pakistan and China, especially with Pakistani forces reportedly using Chinese-made munitions. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pledged his country’s support for Pakistan in upholding its “sovereignty, territorial integrity, and national independence.” The China-Pakistan partnership — long a source of concern for India due to fears of a potential two-front war — complicates recent efforts by Beijing and New Delhi to stabilize their relations, which had deteriorated following violent border clashes in 2020. Despite recent efforts to ease tensions along the India-China border, the boundary remains contested, and both nations continue to vie for regional influence in a bitter strategic rivalry. The China-Pakistan partnership is therefore a persistent concern for India, and one that is likely to draw New Delhi closer to Washington.

The double-edged sword

For India, the recent conflict with Pakistan poses an enduring strategic dilemma: while asserting military strength in the face of persistent threats is vital to its image as a rising power, the risk of a full-scale escalatory conflict could undermine its broader objectives of regional influence and global standing. While the current ceasefire is expected to hold for now, the deep-rooted tensions show no signs of abating, with little indication of any imminent diplomatic engagement to ease hostilities.

The recent conflict has also underscored the limitations of nuclear deterrence, which failed to prevent the outbreak of conventional military exchanges. While both sides have claimed certain tactical victories, the risk of escalation — including the possibility of invoking nuclear capabilities — remains dangerously real.

• Edited by Vice-President Research & Strategy Vina Nadjibulla and Senior Editor Ted Fraser, APF Canada