The Takeaway

The revision of three key security and defence documents marks a historic shift in Japan’s post-Second World War pacifist defence outlook. Due to growing regional tensions, Japan has begun a considerable military buildup, which the government has branded as a “defence-oriented policy” within the scope of the Japanese Constitution.

In Brief

On December 16, 2022, after years of debate, the Japanese cabinet approved revisions to three key security and defence documents: the National Security Strategy (NSS), the National Defense Strategy (previously the National Defense Program Guidelines), and the Defense Capability Enhancement Plan (previously the Medium-Term Defense Program). Although Article 9 of the 1946 Constitution renounces Japan’s right to war, it has been “reinterpreted” on many occasions to expand Japan’s military capabilities in the name of “self-defence.” The most recent revisions have been propelled by what the NSS calls “the most severe and complex security environment” since the end of the Second World War.

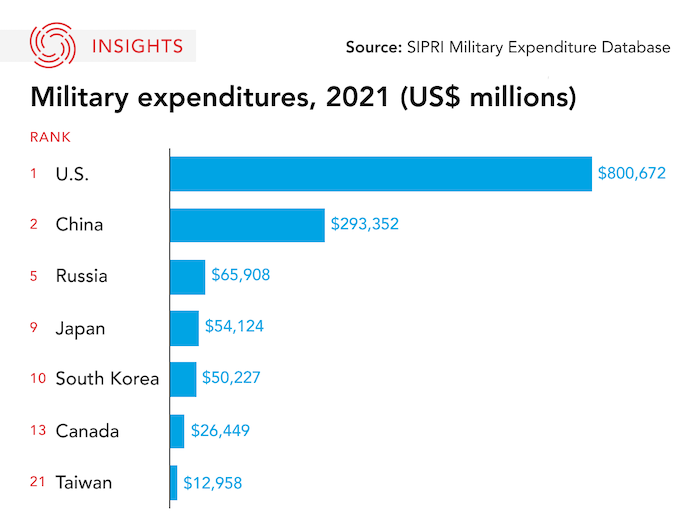

According to Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, the revisions are necessary to enhance the country’s military to make Japan a powerful deterrent and increase its diplomatic power. While Japan has periodically made amendments to its defence strategy and guideline documents, this is the first update to its security strategy in nearly a decade. It is only the second NSS since the postwar Basic Policy on National Defense in 1957. The December security policy revisions are widely viewed as one of Japan’s largest postwar policy shifts due to a new “counterstrike capability,” or the ability to strike bases in enemy territory for defensive purposes – the first time for Japan to approve such a measure in the postwar era – and a doubling of defence spending to two per cent of the country’s GDP by 2027.

Implications

The approval of the three documents marks a major shift in Japan’s post-Second World War pacifist outlook on defence, which has sparked controversy both domestically and internationally. Despite Kishida’s assurance that the revisions, including the counterstrike capability, follow an exclusively “defence-oriented policy,” many pundits have highlighted the dubious constitutionality of Japan’s strengthened military capacity.

While the U.S. and Canada have wholeheartedly welcomed Japan’s increased defence capabilities, it has been met with skepticism from countries like South Korea due to the ambiguity of certain words in the revisions. Meanwhile, China, North Korea, and Russia have strongly condemned Japan’s “remilitarization.” Experts note the use of stronger language towards countries compared to previous defence documents, with the documents calling China the “greatest strategic challenge,” North Korea “a graver, more imminent threat,” and Russia “a serious security concern.”

The new documents outline a defence spending and procurement plan that entails purchasing new missiles, strengthening the country’s missile defence system and cyber defence capabilities, and defence co-operation with partner countries. Several countries have begun co-operation with Japan on new defence technologies. In addition to the planned purchase of U.S. Tomahawk cruise missiles, Japan has allocated significant funds to purchase Norwegian missiles. The country also plans to build a next-generation fighter program with Italy and the U.K.

On December 23, the Japanese cabinet approved its largest ever defence budget for fiscal 2023, accounting for 1.19 per cent of the country’s GDP. A poll conducted by Kyodo News, a Japanese news agency, showed 69.4 per cent of respondents disapproved of the planned tax hike to fund increasing defence spending. The same poll, however, indicated that 50.3 per cent of the respondents approved of Japan’s new counterstrike capabilities. Combined with Kishida’s low approval ratings, the government has temporarily shelved the tax hike. On December 28, Kishida hinted at the possibility of a general election before revisiting the tax issue.

What's Next

-

Increased military co-operation

The Japanese Self-Defense Force (SDF) is expected to increase military partnerships with regional partners such as Australia, India, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Countries such as the U.S. and Canada have also expanded intelligence sharing co-operation with Japan in an effort to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific. Increased technical co-operation such as the exchange of defence technologies may also spark greater regional competition.

-

Revamping the SDF

As Japan’s de facto military, the SDF must address several problems. First are the recent scandals surrounding a captain leaking confidential information and the harassment of a female SDF member. Both incidents have diminished trust in the institution. The second issue is that the appeal of the SDF is low and they have struggled to attract new recruits since at least 2014.

-

Japan’s role on world stage likely to expand

On January 1, 2023, Kishida pledged that Japan would pursue a greater role in diplomacy in response to escalating security threats. Alongside the defence document revisions, Japan also began its two-year term on the UN Security Council, committing to build unity within the UNSC to respond to global issues.

• Produced by CAST’s Northeast Asia team: Dr. Scott Harrison (Senior Program Manager); Momo Sakudo (Analyst); and Tae Yeon Eom (Analyst).