2024 will be an important year for Asia. More citizens will be voting for leaders in Asia than anywhere else in the world. Elections will be held in India, Indonesia, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, South Korea, and Sri Lanka. While 2023 ended on a slightly positive note for U.S.-China relations, following the Xi-Biden Summit in San Francisco, questions remain whether these fragile improvements can hold up in 2024, or will tensions escalate again following the elections in Taiwan and against the backdrop of U.S. presidential elections. Economic opportunities and challenges for Asia are also coming into focus. The region as a whole is forecasted to outperform the global economy in terms of growth. However, uncertainties and skepticism about the future of the Chinese economy are going to persist, given the structural challenges of debt, demography, demand, and continued realignment of supply chains along geopolitical lines. Finally, developments in the region must be seen in the context of the wars in Europe and the Middle East. These wars will continue to preoccupy policy-makers in Ottawa and other capitals in 2024, despite the commitment to deepen engagement with the Indo-Pacific.

Below are 10 things APF Canada will be watching especially closely this year in the Indo-Pacific.

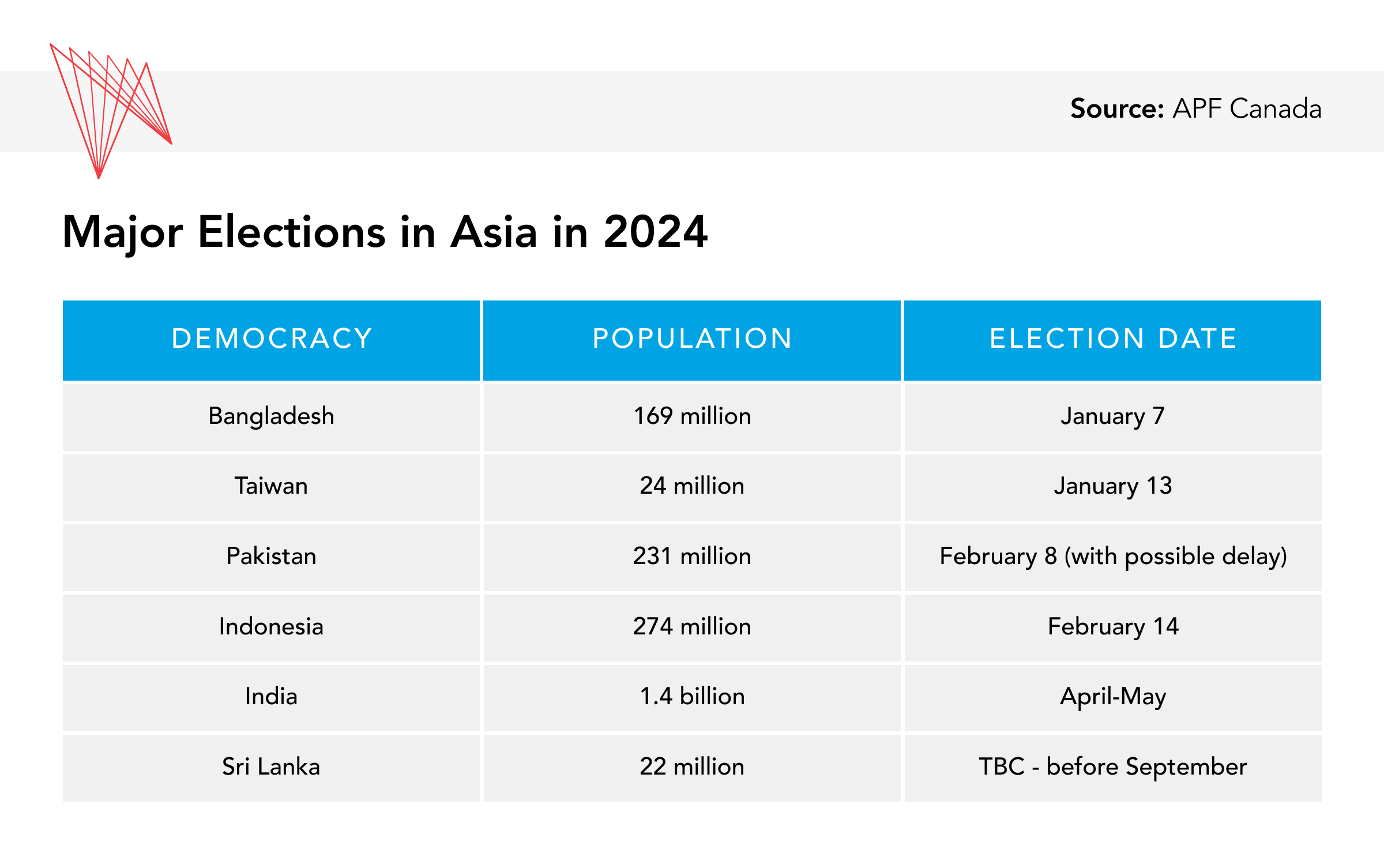

#1 Will Asia’s major democracies stand the test of national elections?

In 2024, voters in several of the world’s largest democracies in Asia will vote on whether to give their incumbent leaders and/or parties another term or make wholesale changes to their elected governments.

The region’s biggest geopolitical nail-biter was the January 13 election in Taiwan, which delivered a win for Lai Ching-te, vice president under the incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Beijing has made no secret of its hostility toward Lai and its deep distrust of his intentions regarding independence from China, and Lai’s post-election statement in support of the status quo will not lessen the Chinese government’s ire.

Moreover, even though Beijing’s hardline approach in the form of thinly veiled warnings to the Taiwanese population seems to have backfired, Chinese President Xi Jinping is not likely to throttle back on the pressure campaign. If anything, some worry things could intensify.

Democracy in Bangladesh, which held a general election on January 7, was under threat even before the first vote was cast. In recent months, the ruling Awami League arrested thousands of opposition members. The opposition’s subsequent boycott of the election cleared the way for a fourth Awami League term and further government actions likely to corrode democratic freedoms related to speech and assembly.

When election season begins in India in April, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its leader, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, look all but guaranteed another mandate.

Internationally, India has been basking in the glow of positive reviews by those encouraging its emergence as a counterweight to China. Domestically, Modi remains as popular as ever; a 2023 Pew Research poll showed that nearly 80 per cent of Indians have a favourable view of the two-term prime minister. However, his critics say he has presided over “an unprecedented consolidation of power, muzzling critical media, eroding the independence of the judiciary and . . . using government agencies to pursue and jail political opponents.”

Two other South Asian countries— Pakistan and Sri Lanka — are expected to hold elections this year while trying to stabilize their economies. Pakistan has been beset by political turmoil since the ouster of former prime minister Imran Khan in 2022. In May, Khan was arrested on corruption charges, but the country’s Supreme Court quickly ruled the arrest unlawful. He was re-arrested in September, which further inflamed his supporters — despite his own anti-democratic track record, Khan remains the country’s most popular politician. Many of these supporters believe, not without merit, that the powerful military establishment will do whatever it takes to keep Khan and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party from taking office. That includes arresting thousands of PTI supporters and strangling freedoms of speech and information.

In Indonesia, front-runner Prabowo Subianto, the country’s defence minister, has selected Jokowi’s son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, as his running mate. The choice may benefit Prabowo, given the outgoing president’s popularity. But it has not helped bolster the country’s democratic image, raising questions about whether Indonesia is following Southeast Asia’s well-worn path of politics as a family business.

#2 What will the Chinese economy’s new ‘new normal’ look like?

After decades of rapid growth, China’s economy is slowing down and is facing severe headwinds. An assortment of headlines from the past year tell part of the story: ratings agency Moody’s lowered its credit outlook for China; foreign direct investment (FDI) turned negative for the first time in 25 years; more than 10,000 millionaires decamped to more favourable locales for the second year in a row; and youth unemployment hit an unprecedented 21 per cent, with some worrying that the actual number could be twice as high.

The causes of these woes vary and include a post-COVID rebound that failed to spur consumer spending, as well as the structural issues of debt, demography, de-risking, and demand.

China’s policy-makers are not without options, and significant policy changes are needed to address both structural and cyclical causes of economic slowdown. In his New Year’s address, Chinese President Xi Jinping signalled that help may be on the way. However, given that President Xi is unlikely to loosen state control over the economy and return to the openness and market-oriented policies of the past two decades, 2024 is unlikely to see changes in the confidence levels of foreign investors and China’s private sector.

#3 Will the region keep a lid on maritime tensions?

For years, armed maritime conflict in the Indo-Pacific has been among the region’s biggest potential flashpoints. The pattern of escalation in 2023 raises the serious possibility that such conflicts may no longer be “potential.”

Of growing concern are repeated clashes between Beijing and Manila over territory in the South China Sea to which both countries lay claim. In 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague ruled unanimously that major aspects of China’s claims were invalid under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). It also concluded that China’s activities, such as illegal fishing and the construction of artificial islands within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone constituted an infringement on the latter’s sovereignty. Nevertheless, China has not only flatly rejected the Court’s ruling but has also doubled down on such activities. In 2023, it repeatedly harassed Filipino resupply missions to an aging ship stranded in the Second Thomas Shoal. The Philippines has issued dozens of diplomatic protests and has summoned the Chinese ambassador, while China has warned the Philippines against taking what it would see as further provocations. As a member of UNCLOS, Canada reiterated its firm support for the Tribunal’s decision as recently as July, stating that Canada stands “with the Philippines and all Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) member states in upholding international law.” In September, the Canadian Navy had several close encounters of its own with Chinese vessels while the former were conducting maritime exercises with the U.S. and Japan in international waters. And, in October, a Canadian surveillance plan conducting UN sanctions-enforcement actions against North Korea was intercepted by Chinese warplanes in “an unsafe and unprofessional manner.”

In a rare bright spot, China reportedly scaled back on these types of intercepts involving the U.S. following the summit between U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping. While the November summit also succeeded in re-establishing China-U.S. military-to-military communications, whether the restraint holds remains to be seen.

#4 Will Canada-India relations recover?

Canada-India relations are still reeling from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s statement in September that “agents of the Indian government” were involved in the June 18 killing of Canadian citizen Hardeep Singh Nijjar in British Columbia. New Delhi called the accusations “absurd” and challenged Trudeau to produce evidence to support his claims.

Then, in November, the U.S. media broke a story about a foiled assassination plot in New York that also implicated the Indian government and seemed to lend credence to the Canadian case. In December, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said of the U.S. case, “if a citizen of ours has done anything good or bad, we are ready to look into it. Our commitment is to the rule of law.”

That commitment will be put to the test as the criminal investigation of the Nijar case in Canada progresses and more information becomes public. Such evidence may make it untenable for New Delhi to draw a distinction between the U.S. and Canadian cases. On the other hand, India’s extensive media hype over the Nijjar case and Modi’s pre-election (see above) appeals to nationalist rhetoric may also make it politically difficult for him and others to walk back some of their criticisms of the Canadian government. As such, we should brace for more volatility in the relationship for the first half of 2024. Political and diplomatic relations will remain tense for the foreseeable future. However, given India’s growing economic and geostrategic significance and the extensive people-to-people ties binding the two countries, Ottawa will need to try to get the relationship back on track, at least on the economic front.

#5 Will the tide turn in Myanmar’s civil war?

2024 marks the fourth year since the military seized power from the elected civilian government in a coup in Myanmar. The February 2021 coup triggered mass protests that have since coalesced into an armed resistance. This armed resistance force has recently scored some triumphs over the country’s military; in October, three ethnic armed organizations, called the Three Brotherhood Alliance, launched a surprisingly effective attack, seizing control of several military bases and border crossings. In addition, the military is grappling with defections and difficulties recruiting new members, and international sanctions have started to bite.

One wildcard in the conflict’s trajectory is China. Beijing’s interest is avoiding instability along its southwestern border and cracking down on criminal activity in that area. On January 12, media reports noted that Beijing had brokered a “temporary ceasefire” between the military government and the Three Brotherhood Alliance. Some experts viewed Beijing’s earlier attempts at negotiating such ceasefires as seriously “misguided,” as it disregards the long history of failed peace initiatives in this region. As recently as December, a China-mediated ceasefire among the same groups quickly fell apart, calling into question whether this month’s agreement will have any greater staying power.

While the military government’s collapse is by no means a foregone conclusion, its defeat would mean a gigantic step into the unknown. Resisting the military government has unified groups that are otherwise traditional adversaries. Once their common enemy is gone, a post-civil war Myanmar could be anything but peaceful, injecting further doubts into the country’s trajectory.

Canada will be watching how the humanitarian situation in Myanmar evolves. Since 2018, it has made Myanmar a policy priority, especially through its support for the Rohingya refugees who have fled violence in western Myanmar and through its involvement in the World Court’s prosecution of the military government for alleged genocide against the Rohingya during a pre-coup phase of violence.

#6 Will Canada ‘institutionalize’ its North Pacific engagement?

In its 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS), Canada singled out Japan and South Korea as regional powers with which it sees opportunities for security co-operation. Both are longtime U.S. allies and vital nodes in preserving the rules-based international order in Asia. Nevertheless, their bilateral relationship has been repeatedly derailed over historical sensitivities.

But following a rare trilateral summit with the U.S. at Camp David last August, Seoul and Tokyo pledged to deepen their co-operation around economic and security issues. Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol also agreed to meet this year for the first in-person summit between the two countries’ leaders in more than a decade.

Immediate questions about the durability of this partnership centre around Kishida’s and Yoon’s political fates. Both have low approval ratings and will have to contend with elections this year, which could hamstring their ability to make bold foreign policy commitments, especially toward each other.

Despite possible tensions in U.S.-South Korea relations, a healthy majority of South Koreans now support co-operation with the U.S. and Japan, especially on security issues. And some experts are optimistic that the recent institutionalization of the bilateral relationship has helped “future-proof” it against challenges to or changes in leaderships. But others are concerned that if Donald Trump is re-elected in the U.S., Washington’s commitment to the trilateral relationship could be in peril, given Trump’s penchant for wanting to unravel the accomplishments of his predecessors.

Canada has made an important contribution to a security issue that is of immediate concern to both Japan and South Korea: the enforcement of UN Security Council sanctions against North Korea aimed at preventing nuclear proliferation. Since 2018, the Canadian military has sent ships, aircraft, and personnel to support multinational efforts to monitor Pyongyang’s sanctions-evasion activities.

Canada’s involvement in security operations on the Korean Peninsula comes at a critical time; as of early 2024, experts were predicting that North Korean belligerence will increase this year. While this is consistent with Pyongyang’s previous pattern of ramping up provocations during a U.S. election year, the frequency of these provocations more than doubled from a previous high of 26 per year in 2016 to 55 in 2022. Moreover, two longtime Korea watchers warned on January 11 that “the situation on the Korean Peninsula is more dangerous than it has been at any time” since the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 and that “Pyongyang could be planning to move in ways that completely defy our calculations.”

Finally, there is scope for Canada to expand its co-operation with North Pacific partners beyond traditional security issues. In its IPS, Canada identified a wide range of issues related to protecting supply chains and other economic security concerns in the North Pacific. In March 2023, moreover, Ottawa proposed a four-way co-operation framework with Japan, South Korea, and the U.S. to counter threats from Russia and China. The proposal was modelled roughly on the U.S.-Japan-India-Australia ‘Quad’ and other minilateral groupings that have become an increasingly nimble and attractive option for Indo-Pacific co-operation.

#7 Will Asia drive AI Governance?

Following the surge in public interest and usage of AI systems based on large language models such as ChatGPT, efforts to manage and regulate AI have accelerated in 2023. How the disruptive technology should be regulated and which countries will be successful in advancing their positions will be actively debated in 2024. Various countries have either already proposed legislation or are on the verge of doing so, with the goal of influencing the international regulatory system. But negotiating global rules to govern emerging technologies is challenging, and even more so when geopolitical strategic competition is at stake. For example, the U.S. and China, two leading players in the field, announced in November their intention to set up a bilateral consultation on AI, but they do not even see eye to eye on what constitutes AI, nor on the safety issues and the risks associated with it. Such disagreements will only complicate their future collaboration.

On December 8, the EU passed a comprehensive law, the AI Act, to regulate artificial intelligence and balance the opportunities it offers with the risks associated with its development and usage. The law is heralded as the world’s first to govern the rapidly evolving technology and aims at setting standards beyond its borders. It has been reported that the EU did not get much traction in rallying Asian governments to their binding approach, with India, Japan, South Korea, and the ASEAN countries prioritizing a less restrictive and more “innovation friendly” approach that is responsive to domestic situations and cultural nuances. In late January, ASEAN is expected to pass its “Guide to AI ethics and governance” at the ASEAN Digital Ministers Meeting. The guidelines are expected to prioritize such an approach.

As such, the growing East-West divide over the development of AI regulations that we have seen in previous years is expected to widen in 2024, fueling the already existing gap in rules and regulations needed to prevent AI from taking a frightening direction.

#8 Will the de-escalation of tensions between China and the U.S. last?

In a relationship increasingly defined by competition and mutual distrust, Washington and Beijing managed to end 2023 on a slightly positive note after presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping met on the margins of the APEC summit in November. The outcomes included a re-establishment of military-to-military communications and China’s agreement to help curb the export of fentanyl-related products. Some observers say what was most significant was that the two leaders managed to meet at all.

Domestic politics in both countries, however, could halt or reverse that momentum. In Washington, taking a hard line on China has become one of the vanishingly few areas of bipartisan consensus. The House Select Committee on the Strategic Competition between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party, created in early 2023, is reflective of this consensus and is increasingly reshaping the American conversation. That includes stronger pressure for de-coupling from the Chinese economy.

Meanwhile, many of the traditional “buffers and stabilizers” that used to undergird the relationship, especially those involved in commercial ties, have come undone.

On the China side, Xi Jinping has concentrated foreign policy decision-making in his own hands. Some say that could lead to foreign policy incoherence and/or miscalculation. Moreover, the tough-on-China rhetoric emanating from the U.S. will only fuel his existing and long-held skepticism of American intentions, and Xi’s “obsession” with security has increased his tolerance for risk and the negative economic consequences of his policies.

The U.S. presidential election in November could inject even more unpredictability into the bilateral relationship, especially if American voters return Donald Trump to the White House. If Biden hangs onto his job, he could face pressure from Congressional Republicans to limit the kinds of summits that happened in November; the above-mentioned House committee’s ranking member, Democrat Raja Krishnamoorthi, said recently that his Republican colleagues were “a little uncomfortable with the amount of dialogue that is happening at the highest levels” between the two governments.

#9 Will Canada rise to the challenge as the 2024 chair of the CPTPP Commission?

On January 1, Canada assumed the role of Chair of the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the decision-making body for the 11-member trade pact. As Chair, Canada is responsible for hosting and supporting the Eighth CPTPP Commission Meeting and notifying all relevant bodies of any decisions made by the Commission.

During Canada’s one-year tenure, Ottawa will be called upon to manage some delicate negotiations, specifically regarding China and Taiwan, which both submitted membership applications in September 2021. The only precedent for admitting new members is the U.K., which will soon become the CPTPP’s 12th member. In that case, more than two years elapsed from the start of accession talks to the conclusion of negotiations (in March 2023). A new member’s entry must be agreed upon unanimously by all members, and as accession talks have not yet begun with either Beijing or Taipei, a final decision on the two applications is not likely to be made on Canada’s watch.

Nevertheless, as APF Canada President Jeff Nankivell suggested in a recent Nikkei Asia story, Canada could “develop some innovative and creative ideas” on how to bring about “a gradual increase in engagement that could help integrate Taiwan’s economy and people” into the CPTPP. Our Distinguished Fellow Hugh Stephens and co-author Jeff Kucharski further opined in a recent APF Canada Policy Brief on the CPTPP bids of China and Taiwan that a new class of membership may be a way forward to include these two aspirants.

Experts have also noted that both China and Taiwan will “offer significant advantages” if they are accepted. But there are also major complications given Beijing’s extremely strong resistance to Taiwan joining any international body. While Taiwan has a stronger case due to its market openness, its application could face pushback from member economies whose governments do not wish to jeopardize relations with China. China, in contrast, would need to undertake major regulatory reforms around issues such as tariffs, competition, and intellectual property rights to meet the criteria for joining the trade pact. The country’s history of ‘weaponizing’ trade could also make existing members wary of accepting its application.

How Canada will handle the issue remains to be seen, but whatever the Commission decides, Canada’s actions as Chair could have major repercussions and set a decision-making precedent for one of the world’s most important trade blocs.

#10 Which side will prevail in the battle over mining in the deep seas?

Last year provided irrefutable evidence of the calamitous impacts of climate change. Even so, 2023 ended in controversy after several states resisted — before finally conceding to — a commitment at the COP28 meeting in Dubai to transition away from fossil fuels.

In 2024, a quieter but no less dramatic episode will play out over another high-stakes environmental issue: mining in the deep seas. Proponents say the seabed floor contains a treasure trove of minerals like cobalt, copper, nickel, manganese, and zinc — ingredients used in green technologies and the defence and aerospace industries. The strongest and most vocal proponents include China, Singapore, a handful of Pacific Island states, and a Canadian mining firm called The Metals Company, which has not shied away from some of the most heated publicity around the issue.

Canada is among the opponents, alongside several developing economies, European countries, and environmental protection organizations. This group has pressed for a ban or moratorium, warning that seabed mining could cause grievous environmental harms, including the release of carbon stored in the ocean floor and contamination of the waters on which many societies rely for food.

While deep seabed mining is not currently permitted in international waters, the UN’s International Seabed Authority (ISA) could pass a set of environmental regulations in July that would greenlight the practice. But the ISA’s transparency and impartiality have been questioned; a 2022 investigative report highlighted its perceived coziness with The Metals Company. Moreover, China, which has taken the lead in the rule-making process, is the ISA’s primary funder, and its various bodies are led and staffed by Chinese bureaucrats. At the ISA’s 2023 annual meeting, China reportedly “single-handedly” halted proceedings on “a precautionary pause on mining licenses,” setting up something of a showdown over the next phase of negotiations.

Acknowledgements

APF Canada thanks Erin Williams, Senior Program Manager, Asia Competencies, for the editorial co-ordination of this project, and recognizes the valuable contributions made by our program managers and all of the research analysts across our regional research teams. We also thank Eva Moreta for the translation of this look-ahead Dispatch and Chloe Fenemore for graphic design support.