As a kid, Chris Labelle wanted to start and run a company. So he chose the Smith School of Business at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, and focused on building his understanding of business fundamentals. He took courses in sales, accounting, marketing. And he joined a unique incubator, the Queen’s Innovation Connector Summer Initiative, which brings together students from multiple engineering and science disciplines and business students and gives them modest support to develop their ideas – and hopefully turn them into companies. It was at the incubator that Chris met mechanical engineers Mitch Debora and Derek Vogt, with whom he would co-found Mosaic Manufacturing after graduating in 2014.

Back in those incubator days, Mitch already ran a 3D printing company. Hospitals, engineering companies, and automotive firms would ask him to print specialty objects, and he’d do it. His clients frequently asked about producing items in different colours and different materials. And that’s the idea Chris, Mitch, and Derek pursued when founding Mosaic Manufacturing, namely helping users of 3D printers expand the range of colours and materials they can incorporate in their 3D production processes.

In the company’s first six months, the three co-founders developed a proof-of-concept product and put the product prototype out into the world. Industry commentators and bloggers quickly started writing about Mosaic’s new technology. The day the first major industry review was released, the company received around 700 expressions of interest in buying the product. Mosaic leveraged that momentum into a Kickstarter campaign that was fundamental to generating its first C$250,000 in orders for the product that would become the first in its Palette line of units and related technologies that add onto 3D printers, allowing them to print in lots of colours and use non-standard materials. Mosaic Manufacturing has released several improvements and upgrades to its original Palette technology, with the Palette 2S Pro its latest iteration.

What exactly is 3D printing?

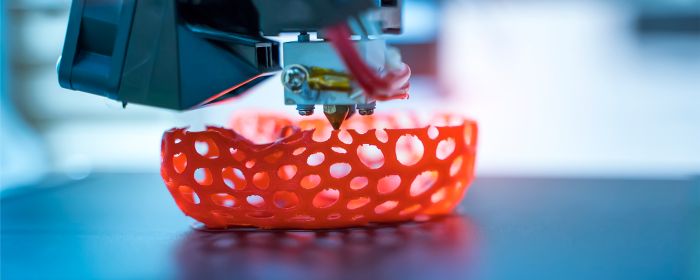

At its essence, 3D printing allows users to create products that are printed layer by layer in three dimensions. Industrial applications of 3D printing include prototyping and iteration in manufacturing, small product runs, while 3D printers are also used to create unique objects by hobbyists.

Most 3D printers use plastic wire coils, or filament, as the primary input material. The 3D printer draws in filament that it melts and adds in layers to build the object being constructed. Filament must be melted at just the right temperature before it is added to an object in a precise pattern in layers of an exact thickness. The process is guided by specialized design and engineering software.

Adding multiple colours, ensuring ultra-smooth surfaces, and automating the process of switching colours is where 3D printing gets very complex very quickly, and these are the complexities Mosaic Manufacturing’s Palette technologies address. Many contemporary 3D printers allow for printing in only three colours and may require the attention of a skilled technician to switch between colours. Mosaic’s technology allows for the use of a fourth colour and new materials in production processes and greatly improves the automation of switching from one colour to the next.

Just before the pandemic hit, Mosaic Manufacturing was growing steadily and had around 25 employees. It manufactured its Palette units in China, sold them to a growing client base primarily in North America and Europe, and conducted product and business development, as well as customer support functions, from its office in downtown Toronto. Then COVID-19 hit, and like the rest of the world, all of a sudden Mosaic Manufacturing was grappling with a future in which nothing was certain.

The COVID innovation

In March 2020, demand for Mosaic Manufacturing’s products and services fell, although it didn’t completely crater. And like other businesses across Canada, Mosaic responded to pandemic restrictions by shuttering its office while its well-established operations turned upside down. The company’s response included redeploying available resources to take on a new and novel project through NGen, Canada’s recently-established advanced manufacturing supercluster, one that responded to an immediate and life-saving need: producing medical-grade face shields for use in hospitals across Southern Ontario.

The pivot was quick and novel; a technology company that helps others improve their 3D printing in effect took on the functions of a small manufacturer of critical personal protective equipment (PPE) within a couple of weeks by re-directing the company’s latent capacity to a related, although previously unconsidered, endeavour. Mosaic leveraged its suddenly under-utilized, high-quality 3D printing capabilities to rapidly begin producing the curved, clear plastic barrier that covers the wearer from above the eyes to below the chin, preventing the movement of droplets from and to the wearer’s face. It was one of four companies to produce face shields through contracts with NGen, which administered a range of contracts with Canadian companies to supply PPE and other essential equipment in response to COVID-19.

Revenue from the face shield project helped cover some of the company’s employees’ salaries at a time when Mosaic couldn’t foresee what the coming months would hold, whether in terms of its short-term sales, the ongoing viability of the 3D printing sector, or more broadly in relation to the spread of the virus or global economic stability. Labelle observed that the face shield project was an opportunity to help keep Canadians safe and healthy in a time of need, to “do something good, and also mitigate some risk on our side.”

Mosaic Manufacturing printed an estimated 20,000 face shields from late March through the end of June when the project wrapped up. And revenues from its established business lines have recovered to near pre-pandemic levels.

Diversifying supply chains and Asia connections

Lockdowns in Canada and elsewhere stopped the production and distribution of all manner of products and economies ground to a halt. While consumers quickly saw shortages of hand sanitizer and surgical masks, manufacturing companies saw supplies of critical components dry up. Factories closed the world over. And closed factories no longer ship products as they had done pre-pandemic. Global supply chains faltered, and no country or company was immune.

Many began to see our reliance on China’s manufacturing strength, built on its appeal as a cost-competitive producer, as a source of supply chain fragility. Closed factories in China meant disruptions everywhere, a concern brought into stark relief at the pandemic’s onset as countries clamoured for supplies of PPE and health authorities searched for alternate suppliers of ventilators. For Canada, production slowdowns in China were not the only threat to PPE supplies – the Trump Administration’s enactment in early April of the U.S. Defense Production Act in relation to ventilator equipment and N-95 masks for a time prevented U.S.-based multinational 3M from exporting its U.S.-made N-95 north of the border. Diversifying supply chains is the new imperative, especially for critical health care inputs.

Against this backdrop, Mosaic Manufacturing’s face shield pandemic pivot might be instructive for Canadian producers and procurement beyond the immediacy of the COVID pandemic. While large-scale manufacturing in Canada is unlikely to be able to compete on cost with China or other jurisdictions in Asia in the foreseeable future, the domestic production of critical components required in the health-care and other priority sectors could become an increasingly large contributor to domestic supply.

Mosaic’s major business learning from the pandemic

For Labelle, the main takeaway from the challenges the pandemic has thrown at Mosaic is the importance of flexibility. He emphasizes that this isn’t just a generic observation but one that is very much rooted in the company’s drastically changed approach to its day-to-day work. Before the pandemic, Mosaic’s culture was quite closed to working remotely. The expectation was that employees worked in the office as doing so was good for morale and productivity for a hardware and technology company working with physical goods.

But COVID-19 has changed that mindset. When the lockdown came, Mosaic moved immediately to remote work. Labelle saw it was important to understand employees’ concerns and to respond quickly to help them feel safe and happy while remaining productive under new circumstances. The results have been impressive. The company has avoided both lay-offs and salary reductions and has even made new hires since the lockdown began. “It is interesting to see what you can do when you don’t have another choice,” Labelle observes.

By mid-July, a small number of Mosaic employees have begun to return to work at the office, wearing masks and following strict physical distancing and sanitization protocols, although the majority of the company’s 25 employees continue to work remotely. Labelle himself has only been to the office once since mid-March, and that was on a weekend to collect mail. Business is back on track, but it looks very different.

Disclaimer: Mosaic Manufacturing’s Co-Founder and Chief Operating Officer, Christopher Labelle, is on the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s Board of Directors. This case study draws on conversations between the author and Mr. Labelle in May and July 2020.