During the past decade, China has made rapid advances in technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and emerged as a leader in many high-tech fields such as artificial intelligence. To continue supporting the burgeoning AI industry, the Chinese government has been devoting huge efforts to nurturing the next-generation AI workforce, implementing AI education programs not only at the post-secondary level but also at the K-12 level, with a model that features robust public-private partnership. China has made significant progress in terms of integrating and instituting AI education in its centrally planned, locally implemented school curriculums. Researchers at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada (APF Canada) have recently examined the current state of AI development across APEC member economies, including China, and the ongoing social momentum to include AI in education curriculums around the world. The team has also conducted a comparative study of Canada’s and South Korea’s diverging experience of introducing AI education at the K-12 level, while highlighting the need to continue drawing lessons from good practices across the region. To complement these analyses, this short report looks at China’s primary and secondary AI education to determine its unique characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses.

China’s Public Education System

China’s public education system is the world’s largest, with 282 million students and over 17 million teachers in about 530,000 schools (excluding extracurricular educational institutions) in total.[1] The Ministry of Education (MOE) administers the macro-level planning, curriculum standards, policy guidance, and budget allocation for China’s primarily state-run education system, with relatively little private sector involvement.[2] Under the MOE, there are provincial-level education departments and city-/county-level education bureaus that are responsible for localizing and implementing the centrally formulated overarching guidelines.

In China, people conventionally refer to “basic education” as the nine years of state-funded, compulsory primary and junior high school education. Starting with a stark literacy rate of 20 per cent in 1949, public school enrolment rates have jumped in the past decades, particularly following a series of reforms in the 1980s, catching up with the levels in high-income countries. The net enrolment rate in primary education and the gross enrolment rate for junior high schools reached 99.94 per cent and 102.6 per cent, respectively, in 2019,[3] and the literacy rate reached 97 per cent in 2018.[4] The education system also underwent significant changes in 2001 with the launch of the landmark New Curriculum Reform policy, which decentralized policy decisions in curriculum management to encourage flexibility and needs-based diversification at the local level. [5]

Notwithstanding significant achievements in internet user penetration in China, urban-rural disparities remain a hurdle in the country’s education system. For information and communications technology (ICT) education such as coding, robotics, and AI, the remaining gap in internet penetration rates across China – with nearly 80 per cent in urban regions versus 59 per cent in rural villages[6] – constantly poses a challenge to education. Ensuring education equality for rural and migrant children (from rural families that are temporarily working and living in urban areas) remains one of the MOE’s top priorities.

Initiatives by the Ministry of Education

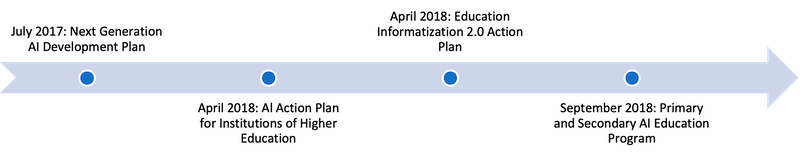

The teaching of artificial intelligence is a relatively recent addition to the information technology curriculum of China’s K-12 education. In 2017, the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan was issued by the State Council as the guiding document of the country’s pursuit of becoming “the world’s primary AI innovation center” by 2030.[7] One of the key areas of this plan is to enhance people’s awareness and use of AI technologies through the promotion of universal AI education – meaning that it is intended to be available to every single student going through the public school system. In particular, the plan proposed the offering of “AI-related courses in primary and secondary schools,” as well as the “construction and improvement of AI public education infrastructure.”[8] Following this country-wide policy, MOE drafted the Artificial Intelligence Action Plan for Institutions of Higher Education in April 2018, listing the “construction of a multi-layer AI education program including that at the primary and secondary school levels”[9] as a major policy action in the effort of nurturing AI talent. Another MOE document released around the same time, the Education Informatization 2.0 Action Plan, also included plans for the “substantiation of IT curriculum with content on AI and coding,” so as to “better adapt to the needs of development in the information era.”[10]

To implement these policies, MOE initiated the Primary and Secondary AI Education Program in September 2018 to work together with city-level science academies, schools, and private sector partners to design top-level AI courses for K-12 students. The program provided schemes to distribute AI teaching equipment to schools as well as guidance on curriculum planning. According to the latest Curriculum Standards for Information Technology (IT) in Ordinary High Schools to be fully implemented by the fall 2022 semester, “primary concepts of artificial intelligence” will become one of the six “optional compulsory modules”[11] in senior high schools. The IT education standards for high schools also stipulate that students have a basic understanding of the “concepts and core algorithms of AI,” familiarity with the “basic AI applications using open-source frameworks,” and “ethical and security challenges in an intelligent society.”[12]

Cities and schools selected to launch pilot AI courses have been given considerable flexibility and autonomy on their curriculum design and choice of textbook. As in the case of IT education, the MOE encourages local education authorities to co-ordinate “the writing and adoption of a textbook that suits the local condition and school schedules.”[13] Since 2018, several versions of AI textbooks have been released – in most cases co-authored by experts in education paired with AI industry practitioners – usually distinguished from one another by their target audience, content focus, and relation to the broader teachings of IT.

Partnerships Between the Private Sector and Academic Institutions

China’s private sector plays an active and instrumental role in complementing the state-run AI education policies. AI and tech companies have functioned as “technical partners” for schools and regional education authorities, co-designing curriculums and textbooks for AI courses at primary and secondary schools. They also provide partner schools with the necessary tools and platforms for teaching and learning AI skills.

Since the Development Plan was announced in 2017, a number of Chinese tech and AI unicorns have been actively channelling their strengths and resources into public education. Among the first movers in this field was Hong Kong-based AI company SenseTime, who collaborated with the Massive Open Online Course Center (MOOC Center) at East China Normal University to publish the Fundamentals of Artificial Intelligence (High School Edition), said to be the world’s first AI textbook, in 2018. The company later established a separate subsidiary called SenseTime Edu to support the offering of an integrated, “whole package of AI education solutions.”[14] This includes initiatives such as providing learning platforms, labs, and educational robots leveraging its proprietary technologies; compiling a K-12 all-age textbook series; and offering teacher training and certification programs.[15]

Meanwhile, iFlytek, a Chinese intelligent speech/AI leader and established name in smart education, partnered with Northwest Normal University and the National Center for Educational Technology in 2018 to create the first junior high school AI textbook. The textbook includes the exclusive use of an online practice kit developed by iFlytek. The company has also organized teacher training sessions and robotics contests for the K-12 audience.

While companies provide the technical side of curricular design, top universities in China, such as the aforementioned East China Normal University and Northwest Normal University, have mainly been supporting these initiatives by providing pedagogical support for the drafting of AI textbooks and curriculums. East China Normal University prioritized work in the intersection of AI and education by founding the Shanghai Institute for AI Education (iAIE) in 2020.[16] Although its current focus is on using AI technologies to empower education, the institute will be well positioned and endowed to generate resources for teaching AI as a subject down the road.

In addition, some institutions and associations are playing more of a convening role, bringing stakeholders together to discuss issues related to AI education. One recent example is the AI Education Conference for Primary & Secondary Schools[17] co-organized in July 2021 by the Chinese Association for Artificial Intelligence, the High School Affiliated to Renmin University, and a number of business partners, including Future Gene, iFlytek, and Walnut Programming. Experiences from some of the earliest and most successful pilot programs were shared during the sessions.

Strengths and Weaknesses of China’s AI Education at the Primary and Secondary Level

China’s successful integration of AI education at the K-12 level can be attributed to several factors. The Chinese government views domestic research, application, and innovation in artificial intelligence as a matter of strategic importance, for which developing an AI talent pool and pipeline is critical. Although the MOE has shifted from “direct control to macro-level monitoring of the education system,”[18] it still wields unilateral power in the country’s broad education agenda-setting and decision-making processes. While the MOE takes the lead in setting up overarching frameworks and providing the jump-start, these centrally directed initiatives have been quickly followed by implementation at the local level by practitioners. Backed by the policy commitment at the state level, AI education for K-12 has attracted the interest of private sector stakeholders and created hype in the market.

The teaching of AI also benefited from the rapid development of China’s AI industry itself and by the wealth of experience accumulated in recent decades from the many existing school-industry partnerships on IT education. China’s generation Z (born between the late 1990s and the early 2010s) grew up in the midst of the country’s fastest economic expansion and modernization, and they have been exposed to digital technologies since birth. Even before AI became part of their school curriculum, many of them gained some exposure to AI through the internet, TV, and print media. Placing a high value on the learning of science and technologies, students’ familiarity and interest are important foundations for AI education to be well received in schools.

More broadly speaking, China nowadays is likely deploying AI and other emerging digital technologies more than most other AI powers do. Both policy-makers and the public are more readily accepting of experimenting with and installing new technologies that they deem to enhance the efficiency and convenience of their work and life. Therefore, there are already a variety of options available, not just in IT and sciences but also in linguistics, psychology, and social studies, for the students’ learning and practising of AI technologies through hands-on, real-life applications. It is also in this context that cutting-edge innovations, including artificial intelligence, are seen as promising occupations in the eyes of students and parents, and thus are appealing in the early stages of education.

On the flip side, the most salient weak spot in China’s current public school education on AI is the lack of a clearly defined, systematic standard for what should be taught at each level.[19] The existing AI curriculums and textbooks, for instance, usually differ in their content arrangements and day-to-day approaches, some of which may not fit students’ cognitive ability and level of knowledge in science and mathematics, and may not adequately prepare students for their deeper dive at the post-secondary level.[20] Another limitation lies in the shortage of qualified, experienced teachers for this relatively new subject – only 35.2 per cent of teachers surveyed, most of whom work at more advanced coastal-region demonstration schools where pilot programs are usually rolled out first, had some experience teaching AI-related content. About a third of these teachers further expressed a lack of confidence in their qualification to teach AI courses.[21]

In addition, much work remains to be done on building the supporting infrastructure for AI education. The majority of schools that have launched AI courses so far did not build a dedicated AI lab, but instead have used their existing IT labs, which are often not adequately equipped for AI teaching.[22] Students in rural areas will continue to be more severely challenged in their access to IT and tech resources. The fact that AI education is currently more of a privilege for the developed regions and schools – where pilot courses first get rolled out – could potentially further exacerbate the problems of regional disparity and the digital divide. Recent survey results indicate that 85.2 per cent of students enrolled in demonstration schools, compared to 67.3 per cent in regular public schools, have some understanding of AI,[23] and this figure would likely go down even further for the rural population. Bridging the gap related to exposure to AI – especially putting in place the necessary facilities and resources to give children an equal footing in learning AI – remains a huge task for the MOE, schools, and their partners.

Conclusion

In building its AI industry, the Chinese government has very much played a macro-level direction-setting and investor-like role, and it is now acting similarly on the AI education front. Even though China’s national education authority operates in a more decentralized manner now than it did decades ago, its decisions remain powerful and are taken very seriously by local education practitioners and the private sector. Public-private partnerships on AI education take shape differently in each country, but China’s powerful state actor ensures that these partnerships have somewhat an equal presence and role to play for the pedagogical and technical sides.

Although still in the early stages of implementation, China’s AI education model offers an alternative for AI educators in Canada to look at – despite different education systems, many end goals are shared, and some of the existing challenges are in fact quite common. It is hoped that educators in Canada will recognize the importance of nurturing the next-generation AI talents earlier in schooling and can draw inspiration from the Chinese experience in terms of initiating its own model that orchestrates private and public efforts and attracts all kinds of partners for the much-needed co-ordination.

Endnotes:

[1] 中华人民共和国教育部 (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China), “中国教育概况——2019年全国教育事业发展情况,” moe.gov.cn, August 31, 2020, http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/s5990/202008/t20200831_483697.html.

[2] OECD, “Education in China: a Snapshot,” oecd.org, 2016, https://www.oecd.org/education/Education-in-China-a-snapshot.pdf.

[3] 中华人民共和国教育部, “中国教育概况,” moe.gov.cn, August 31, 2020. The gross enrolment ratio is the total number of students enrolled in a specific level of education divided by the country’s total population in the official age group corresponding to this level of education, and thus it can be more than 100%.

[4] UNESCO Institute for Statistics, “Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) – China,” The World Bank, September 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=CN.

[5] Lv Shihu, Zhou Ting, “School-Based Curriculum Development in Mainland China,” in Curriculum Innovations in Changing Societies (Rotterdam: SensePublishers, 2013), 271-189.

[6] 中国互联网络信息中心 (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC)), “第48次中国互联网络发展状况统计报告,” sinaimg.cn, August 2021, https://n2.sinaimg.cn/finance/a2d36afe/20210827/FuJian1.pdf.

[7] Jia He, “The Next Generation AI Development Plan — What’s Inside?,” medium.com, August 10, 2017, https://medium.com/@jiahe/the-next-generation-ai-development-plan-whats-inside-72824a9bcc3.

[8] 中华人民共和国中央人民政府 (Government of the People’s Republic of China), “国务院关于印发新一代人工智能发展规划的通知,” gov.cn, July 8, 2017, http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/content/2017-07/20/content_5211996.htm.

[9] 中华人民共和国教育部, “教育部关于印发《高等学校人工智能创新行动计划》的通知,” moe.gov.cn, April 2, 2018, http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A16/s7062/201804/t20180410_332722.html.

[10] 中华人民共和国教育部, “教育部关于印发《教育信息化2.0行动计划》的通知,” moe.gov.cn, April 13, 2018, http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A16/s3342/201804/t20180425_334188.html.

[11] “Optional compulsory modules” (选择性必修课程 xuanzexing bixiu kecheng) are extensions from the required modules of a subject. These are determined by the MOE and their content do not vary as much as the elective modules. Since IT is not a subject that is tested in the college entrance exam, some of its optional compulsory modules will be tested in the senior high school academic proficiency exams that students have to pass to graduate, while others (including the AI module) will not be tested but will be included as part of the evaluation for students who take the module. For more information, see: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A26/s8001/202006/t20200603_462199.html.

[12] 中华人民共和国教育部, “教育部关于印发《普通高中课程方案和语文等学科课程标准(2017年版)》的通知,” moe.gov.cn, December 29, 2017, http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A26/s8001/201801/t20180115_324647.html.

[13] 中华人民共和国教育部, “教育部关于在中小学普及信息技术教育的通知,” moe.gov.cn, 2000, http://www.moe.gov.cn/s78/A06/jcys_left/zc_jyzb/201001/t20100128_82088.html.

[14] GETChina Insights, “The World’s Most Valuable AI Unicorn is Implementing Education Initiatives in China,” medium.com, July 4, 2019, https://edtechchina.medium.com/the-worlds-most-valuable-ai-unicorn-is-implementing-education-initiatives-in-china-e53995dda504.

[15] SenseTime, “SenseTime Unveils SenseTime Edu Brand to Promote AI Education and Talent,” sensetime.com, September 23, 2020, https://www.sensetime.com/en/news-detail/54844?categoryId=1072#:~:text=SenseTime%20believes%20education%20is%20the%20engine%20for%20driving%20future%20innovation.&text=The%20SenseTime%20Edu%20brand%20features,primary%20and%20secondary%20school%20students; 传习帮 (chuanxibang), “商汤科技成立“商汤教育”子品牌,AI教材已实现基础教育学段全覆盖,” sohu.com, September 23, 2020, https://www.sohu.com/a/420295947_120030331.

[16] East China Normal University, “ECNU’s Shanghai Institute for AI Education Founded,” ecnu.edu.cn, December 29, 2020, http://english.ecnu.edu.cn/02/a2/c1703a262818/page.htm.

[17] 中国人工智能学会 (China Association for Artificial Intelligence (CAAI)), “2021中小学人工智能教育大会成功举办,” sina.com.cn, July 27, 2021, https://k.sina.com.cn/article_2280366510_87eba1ae019010e1d.html.

[18] OECD, “Education in China,” oecd.org, 2016.

[19] GETChina Insights, “The World’s Most Valuable AI Unicorn,” medium.com, July 4, 2019.

[20] 于勇, 徐鹏, 刘未央 (Yu Yong, Xu Peng, Liu Weiyang), “我国中小学人工智能教育课程体系现状及建议——来自日本中小学人工智能教育课程体系的启示,” 中国电化教育 no.8 (2020), http://www.chedc.com/4101.html.

[21] 中国青少年科技辅导员协会 (China Association of Children’s Science Instructors), “中小学阶段人工智能普及教育现状调研报告,” cacsi.org.cn, November 26, 2018, http://www.cacsi.org.cn/Uploads/article/20181227/1545878117221139.pdf.

[22] 姜慧梓, 黄哲程 (Jiang Huizi, Huang Zhecheng), “人工智能将进高中课堂,这届同学要和AI一起长大了吗?,” bjnews.com.cn, April 11, 2019, https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/155496957114984.html.

[23] 中国青少年科技辅导员协会,“中小学阶段,” cacsi.org.cn, November 26, 2018.