New Zealand has been heralded as one of the countries with the most successful COVID-19 containment response, quickly putting together strict policies aimed at not only containing but eliminating the virus in the island country. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern moved the country to Alert Level 4, the highest level, on March 25, imposing an initial four-week, nation-wide lockdown requiring people to stay at home. Viewing the spread of the virus as under control, Ardern moved the country down to Alert Level 3 on April 27, which allows for slightly expanded social ‘bubbles’ while maintaining physical distancing.

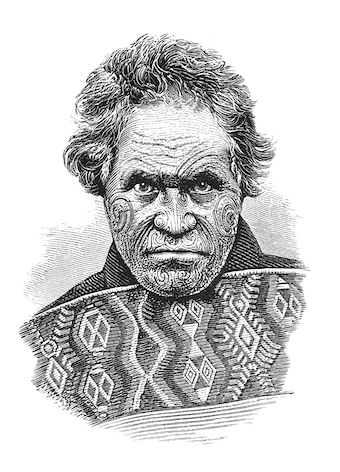

New Zealand’s national success, however, masks broader socio-economic and health inequalities within the country, notably between the Indigenous Māori and Pākehā, or New Zealanders of European descent. Experiences in Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand) suggest that responding to effects of COVID-19 for Indigenous communities, including those in Canada, requires tailored, co-developed, and Indigenous-led approaches that address wider socio-economic and health disparities.

Past pandemics inform current responses

According to New Zealand’s 2018 Census, the country’s 776,000 Māori account for about 16.5 per cent of the national population, and the 382,000 Pasifika (Polynesian and Melanesian migrants who call Aotearoa home) account for another eight per cent. While the percentage of Indigenous people and the integration of Māori culture, economy, and politics is much higher than in Canada, where Indigenous people account for 4.9 per cent of the population, Indigenous people in both countries are at a higher risk to pandemics than non-Indigenous people due to underlying health and societal issues ranging from chronic diseases and poverty to a lack of adequate housing. These factors made the Māori particularly vulnerable to previous pandemics. For example, five per cent of the Māori population died during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic (Spanish Flu) compared to 0.006 per cent of the Pākehā population. During the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, mortality rates for Māori and Pasifika were 2.6 times and 5.8 times higher than for Pākehā.

To help decrease vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, Māori doctors and health experts established in early March Te Rōpū Whakakaupapa Urutā, the National Māori Pandemic Group, to address the shortage of COVID-19-related planning with and for Māori. The group has also been working with government to refine COVID-19 responses. Within New Zealand’s COVID-19 stimulus and aid budget launched on March 17, C$46.8 million was set aside to mitigate hardships for Māori businesses and communities. C$25 million of this amount is funding health services, C$840,000 is going toward advice and planning for businesses, and the remaining C$21 million is earmarked for community outreach and Māori-driven health initiatives.

Worsening health and economic disparities

Most of New Zealand’s cases are linked to international travel. Maori communities have not yet been disproportionately affected, but the current situation masks a potential crisis in waiting. According to findings released by a research centre at the University of Auckland in April, Māori could be 2.5 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than Pākehā. Should community spread occur in Māori communities, the outcome could be devastating. The higher rates of chronic conditions among Māori raise the probability of serious COVID-related complications. These conditions in turn are exacerbated by inadequate access to health care and prescription drugs. In a 2019 study, close to half of Māori participants reported cost barriers to care, and one in five skipped medicines. At the same time, the prevalence of crowded, multi-generational housing in Māori communities leaves elderly members of the community vulnerable to viral transmission from other household members.

Economic determinants of health are likely to worsen as a result of the pandemic. The Māori economy, dominated by primary sector industries such as fishery and forestry, was hit early by the pandemic as orders from Asia slowed. At the same time, Māori are more likely to be laid off because they are more likely to have jobs that require physical contact – i.e. jobs that cannot be done from home, such as store clerks and social workers. New Zealand Treasury’s best-case scenario estimates – with which the country is currently on track (i.e. one month at a Level 4 lockdown) – place the national unemployment rate rising from four per cent to 13.5 per cent. With Māori unemployment at 8.2 per cent, more than double the national rate in the last quarter of 2019, there are fears that even this best-case scenario could push Māori unemployment into the double digits. Without adequate mitigating responses, a deep recession could compound existing inequalities in New Zealand and put Māori at an acute disadvantage, leading to worse mental and physical health outcomes for years to come.

Māori concerned with government response

The government released its Initial COVID-19 Māori Response Action Plan on April 16, about a month after New Zealand entered a national lockdown. The plan, which recognizes that the response models used in previous pandemics “preferentially benefited non-Māori,” vows to fund Māori health provider networks, involve and consult Māori organizations, provide medical supplies to Māori communities, and track Māori’s COVID-19 outcomes. On April 20, the government again acknowledged that there are “devastating health inequalities” in New Zealand affecting Māori and Pasifika communities, and announced that it would thus delay downgrading the country’s alert level by five days to a minute before midnight on April 27.

Despite the government’s use of aspirational language, Te Rōpū Whakakaupapa Urutā has lamented the Māori Response Action plan’s lack of clear objectives, actions, and timelines, calling it “all words, no action.” The group also argues that it devolves almost all health-care responsibility to Māori communities while doing little to prod those in mainstream health care to ensure equitable care. Additionally, the plan does not address reductions in non-COVID care as a result of shifted priorities and patients’ higher reluctance to visit hospitals and clinics during a pandemic.

To resolve these problems, the group has demanded the government ensure the presence of Māori leadership at every level of COVID-19 response so that their needs are better taken into account. Māori voices at decision-making bodies could enable those bodies to draft tailored action items and provide well-defined guidance to families in vulnerable communities and their health-care providers. Such voices could also help safeguard government response plans from becoming detached from on-the-ground needs and constraints.

Te Rōpū Whakakaupapa Urutā has also asked the government to immediately collect and analyze high-quality ethnicity data while monitoring the overall health and disability system for areas of inequitable service. Not only is such data important for containing the spread of COVID-19 in communities that are especially vulnerable, but they also enable the government to monitor whether the provision of non-COVID health care is disproportionally curtailed for Māori communities.

Reflecting on Canada’s COVID-19 response

Indigenous peoples in Canada face many of the same challenges as Māori in New Zealand in health, socio-economic, and political inequities, and similar complications arise in both countries as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The comparison isn’t exact: inadequate access to clean water, for example, is more common in Indigenous communities in Canada. Nonetheless, the Māori experience during the current crisis is a source of insight, particularly on the topics of data monitoring, business-as-usual care, and policy, programs, and service co-development.

Health professionals and Indigenous advocates in Canada have made similar demands to Māori experts in terms of targeted data collection within Indigenous communities. The federal government has so far released no plan to collect and analyze any data on health-related inequities among different communities and groups, though some provincial and municipal governments have begun exploring options. Additionally, the need for Indigenous involvement is becoming increasingly apparent. In the case of New Zealand’s COVID-19 Māori Response Action, the lack of Māori input in the process threatened to turn good intentions into unactionable platitudes. In Canada, the absence of Indigenous co-development of budgets has also led to funding allocations that neglect the needs of off-reserve Indigenous populations and most Indigenous businesses.

Indigenous peoples in different countries across the Asia Pacific have long made cross-border connections throughout the region and with people in Canada to learn from and support one another. It is high time that the Canadian government sought to do the same – starting with recognizing how well-intentioned response plans can still fail to address Indigenous needs without community monitoring and policy co-development.