This week marks the two-year anniversary of the 2021 military coup in Myanmar, which abruptly ended a promising democratic transition and sparked a violent conflict that has engulfed many parts of the country. Despite the initial uptick in international attention and condemnation, the crisis has largely faded from the headlines. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, recently lamented that the crisis has largely been forgotten, stating, “What’s missing more than anything is political will. We know what needs to happen, but we just have not seen the political will demonstrated to take this action.”

The political will remains strong in Canada. Myanmar’s human rights situation has been a focus of Canadian foreign policy, especially since the military escalated atrocities against the Rohingya minority in 2017. How has Canada’s policy withstood the fluidity in Myanmar’s security and humanitarian situation over the last two years? Does Canada have the political will to continue to push for international action? As we look ahead, will our existing policies be adequate to address new developments and support Myanmar citizens in the coming year and beyond?

Abrupt and Shocking End to Myanmar’s Democratic Experiment

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military, claiming constitutional authority, seized power from the democratically elected government and has continued to rule under “emergency provisions” ever since. The military generals claimed the November 2020 election was fraudulent, though it was widely considered free and fair among internal and external election observers. Following the military’s seizure of major state institutions and the immediate imprisonment of democratically elected leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, the population was quick and vocal in its rejection of the return to military rule.

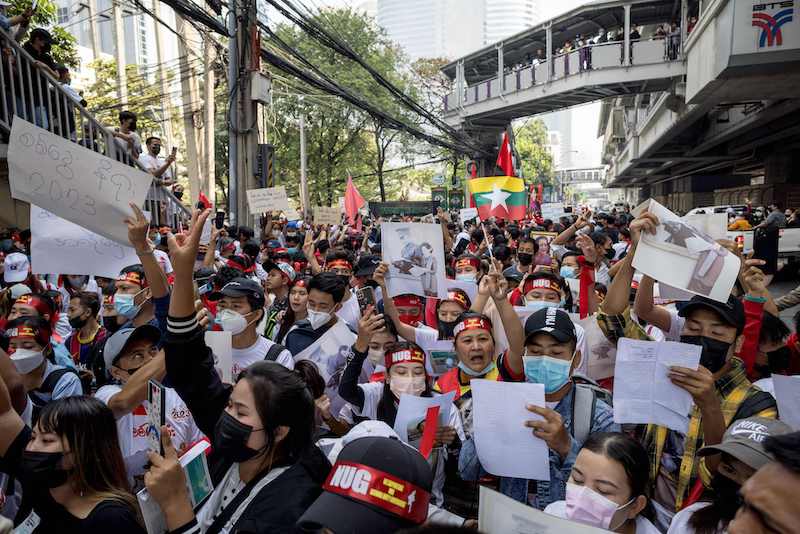

Nationwide strikes and mass protests soon emerged across the country as part of an organized campaign of resistance known as the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM). Hundreds of thousands of citizens gathered in the streets, and strike campaigns forced hospitals, banks, schools, and government ministries to close in the weeks following the coup. Through these resistance movements, citizens of different ethnic groups have come together in an unprecedented demonstration of unity in a country where violent ethnic conflict has been a fact of life since independence in 1948.

This co-operation among civilians has coincided with co-operation among political and armed groups opposed to the military. In April 2021, ethnic leaders and elected officials who managed to evade the military’s dragnet formed the National Unity Government (NUG), a shadow government that has the support of major international players, such as the U.S., and continues to represent Myanmar in the United Nations with the approval of the UN General Assembly. While not necessarily united on all issues, many ethnic armed organizations across the country responded to the coup by condemning the junta and vowing to stand with the protesters and pro-democracy forces. These armed groups continue to escalate their opposition to the military, and some have formed alliances.

The junta has responded with almost unrestrained brutality against civilians and armed groups alike. It has attacked civilians, imposed shutdowns on internet access and mobile and social media platforms, imprisoned journalists and political opponents, and forced thousands of citizens from their homes. Unsurprisingly, the casualties continue to mount. While some reports claim the junta has killed around 2,700 people, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Group estimates that there have been more than 30,000 fatalities. In addition, more than one million people have been displaced, and more than 17,000 have been detained since the coup.

The junta recently announced that it was determined to hold a national election by August 2023, although there is some speculation that its extension of the state of emergency could push back the timeline. Since Myanmar’s constitution only permits two years of emergency rule, if the junta goes ahead with elections, many observers expect them to be fraught with extreme violence and fraud. Ethnic armed groups have claimed that any military-led election will not be tolerated or accepted. Leaving no doubt about the seriousness of these threats, attacks on election offices by these groups have already begun.

The current state of crisis in the country is only expected to breed greater conflict in the coming months. How is the international community responding? And how can Canadian policy adapt to the evolving circumstances in Myanmar?

International and Regional Responses

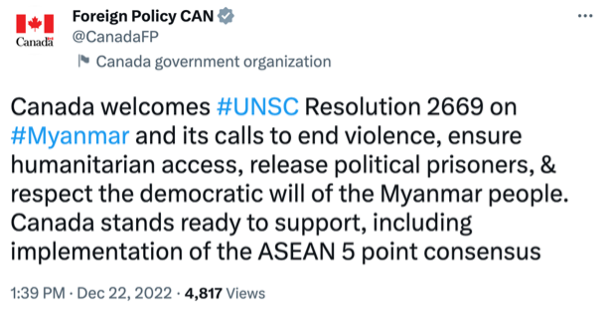

The international response to the coup includes arms embargos and strong economic sanctions on junta leaders, including new sanctions by Canada, the U.S., Australia, and the U.K. against military-linked firms. In 2021, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), of which Myanmar is a member, adopted a Five-Point Consensus strategy to help resolve the conflict. However, the junta largely ignored the strategy, and except for banning military officials from attending future summits, it has been weakly enforced by the bloc. The U.S. and others have criticized ASEAN, urging it to engage directly with the NUG to move forward.

In the face of significant criticism, ASEAN leaders met in November 2022 to review and amend the consensus strategy. The new framework provides additional points of action, including space to engage with the NUG and goals to set more actionable items and timelines. But is this too little too late? Recent commentary suggests that a national election, whenever it is held, might give some ASEAN members the pretext they need to move on from dealing with Myanmar altogether. ASEAN’s inability to act quickly to end the conflict has boosted skepticism about its effectiveness and has some critics arguing that the United Nations should deal with the crisis.

In December 2022, after almost two years of split decisions, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted its first-ever resolution on Myanmar. The resolution condemns the military’s execution of pro-democracy activists, urges the military to release arbitrarily detained prisoners, and demands an end to all forms of violence in the country. The historic resolution was passed with 12 yes votes and three notable abstentions – from China, Russia, and India. Russia’s UN ambassador claimed that it did not view the situation in Myanmar as a threat to international security, but its abstention was perhaps surprising given that in June, Moscow pledged to strengthen its defence co-operation with Myanmar. India, a neighbour of Myanmar, claimed that the UNSC resolution was not the best option for dealing with the situation, and despite not vetoing the resolution, worried that it would only exacerbate the conflict and instability.

China’s abstention does not necessarily signal direct support for the NUG or opposition forces, and its former foreign minister, Wang Yi, expressed China’s continued support in June for the military government’s “legitimate interests.” Nevertheless, it could signify a very subtle moderation in Beijing’s relations with the junta. On the one hand, while most governments and foreign investors have distanced themselves from the junta since the coup, China has maintained a relationship, not least of all by continuing to make significant investments in the country. On the other hand, abstaining from the UNSC vote instead of vetoing it could be a departure from Beijing’s previous pledges of support, and echoes China’s recent non-response to the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation Summit, a regional meeting intended to be hosted by the junta in late 2022.

But the UNSC resolution, no matter how symbolically significant, nonetheless lacks any enforceable action to be taken against the junta to help end the conflict. What is needed, according to Tom Andrews, the UN’s Special Rapporteur, is “targeted, coordinated action . . . including coordinating sanctions, cutting off the flow of revenue that is financing the junta’s military assaults, an embargo on weapons and dual-use technology and robust humanitarian aid.” How does Canada’s Myanmar policy respond to these needs?

Canada’s Crisis Response

In recent years, Canada’s diplomatic relationship with Myanmar has been mainly driven by humanitarian objectives. Canada was the first country in the world to officially recognize the Rohingya crisis as a genocide and was a key player in applying international pressure on Myanmar through various international organizations, including the UN, ASEAN, and the Commonwealth. Since the escalation of the Rohingya crisis in 2017, Canada has announced millions of dollars in aid and appointed former Ontario Premier and former Liberal Party of Canada leader Bob Rae as its Special Envoy to Myanmar.

In 2018, Rae’s report on the situation in Myanmar included recommendations on the role Canada could play, highlighting three key challenges: 1) the humanitarian crisis; 2) the political situation involving the military’s abundance of control; and 3) issues of accountability and impunity for crimes against humanity. These recommendations focused on the need to increase international assistance and stressed the importance of co-ordinating with like-minded international partners in pushing for accountability in the international arena.

In response, the Trudeau government announced its strategy to address the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar and Bangladesh. The strategy focused on humanitarian needs, improving access to basic services, and promoting inclusive governance. Canada provided C$300 million in international assistance over three years, targeting improving food security, access to health services, safety and living conditions at refugee camps, and support for women and girls. Canada also pushed for improved co-operation among international partners by launching an International Working Group on the Rohingya crisis and providing increased support to various organizations in Myanmar.

In 2020, in line with this strategy and its commitment to accountability, Canada expressed its support for and interest in joining the proceedings at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) against Myanmar’s military for perpetrating genocide against the Rohingya. In July 2022, the ICJ decided to hear the application against Myanmar, originally filed by the West African nation of The Gambia in 2019, but with Canada playing an important behind-the-scenes role. While the ICJ case is in response to the Rohingya crisis, we might expect similar cases in the future, as there are already credible allegations that the junta has committed many more war crimes since the 2021 coup.

Remaining Responsive to a Dynamic Situation

In June 2022, Canada announced the next phase of its Myanmar strategy. In response to the escalating crisis in Myanmar, the strategy expands the range of actors it seeks to support, which now includes journalists, human rights defenders, civil society activists, and other anti-junta forces. It also includes targeted funding to support humanitarian partners in continuing to address the immediate needs of the Rohingya and other vulnerable communities.

There is great speculation about how the upcoming year will unfold in Myanmar. Some believe the junta is on shaky ground. But even if there are reasons to be moderately optimistic that the military regime could fall, a transition back to democracy would be far from straightforward. And if the junta retains its grip on power, the international community will need to continue to consider how best to effectively apply pressure on military leaders and support resistance forces. If opposition forces were to be successful, it would be vitally important for Canada and the international community to continue emphasizing support for pro-democracy actors and assisting in rebuilding economic, political, and civil society institutions throughout the country.

For Canada, the best way to support Myanmar moving forward is to continue playing a supporting role among international partners and institutions. That includes maintaining its support for the Rohingya, whose situation, according to recent reports by Human Rights Watch, has been exacerbated in the last two years.

Canada can also play an important role in Myanmar’s future by continuing to address key humanitarian dimensions of the crisis. Specifically, Canada’s Feminist Foreign Policy presents an opportunity to focus Canada’s efforts most prominently on the gendered impacts of the coup and ongoing conflict.

Myanmar’s military has a history of enforcing patriarchal gender norms, marginalizing women, and committing acts of gender-based violence. The coup and ensuing conflict have effectively halted any progress in achieving women’s rights in the country. In fact, it has served as a direct physical threat to women and girls, especially those in conflict zones. A recent report by the National Unity Consultative Council (NUCC) in Myanmar claims that junta forces have killed at least 308 women and girls in the last two years. The NUCC claims that the military has “adopted rape, torture and sexual abuse of civilians as a weapon of war.” The trafficking of women and girls also remains a serious concern, with increased conflict and economic devastation making them more vulnerable. Canada should apply its expertise in gender equality and ensure its international aid flows to organizations that protect and promote the rights of women and children in Myanmar.

In addition, Canada’s more recent focus on internet freedoms presents an opportunity to concentrate on the human rights abuses associated with repressive digital tactics used by the junta. Internet shutdowns and other digital disruptions are common tools of repression used by governments to halt the flow of web-based communication. While not entirely new in the history of Myanmar’s military, the internet shutdowns, mobile and social media bans, online censorship, and digital surveillance imposed over the past two years have had more serious consequences than ever before.

Although Myanmar’s future remains highly uncertain, Canada and its international partners should be thinking and planning ahead on how best to help ensure that the country’s citizens make a transition back to democracy. For Canada, this means continuing and expanding a strong humanitarian agenda to protect and promote human rights, especially for those most vulnerable.