Critical undersea infrastructure (CUI) — including fibre-optic cables, offshore oil rigs, and gas pipelines — is essential for global communications and economic security, yet faces growing threats. In recent months, Taiwan has seen a spike in cable cuts — five incidents already in 2025 — while similar sabotage has appeared in the Baltic Sea, especially after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Undersea cables are also highly vulnerable to natural disasters and accidents, which makes it difficult to attribute damage to malicious actors. At the same time, the cost and complexity of repairing these systems far exceed the effort required to sever them. This may be why states such as China and Russia have allegedly turned to covert attacks on CUI as a low-risk, cost-effective “grey-zone” tactic. Through such shadowy “grey-zone” operations, Beijing may be probing the resilience of its neighbours and contesting U.S. influence in key maritime regions.

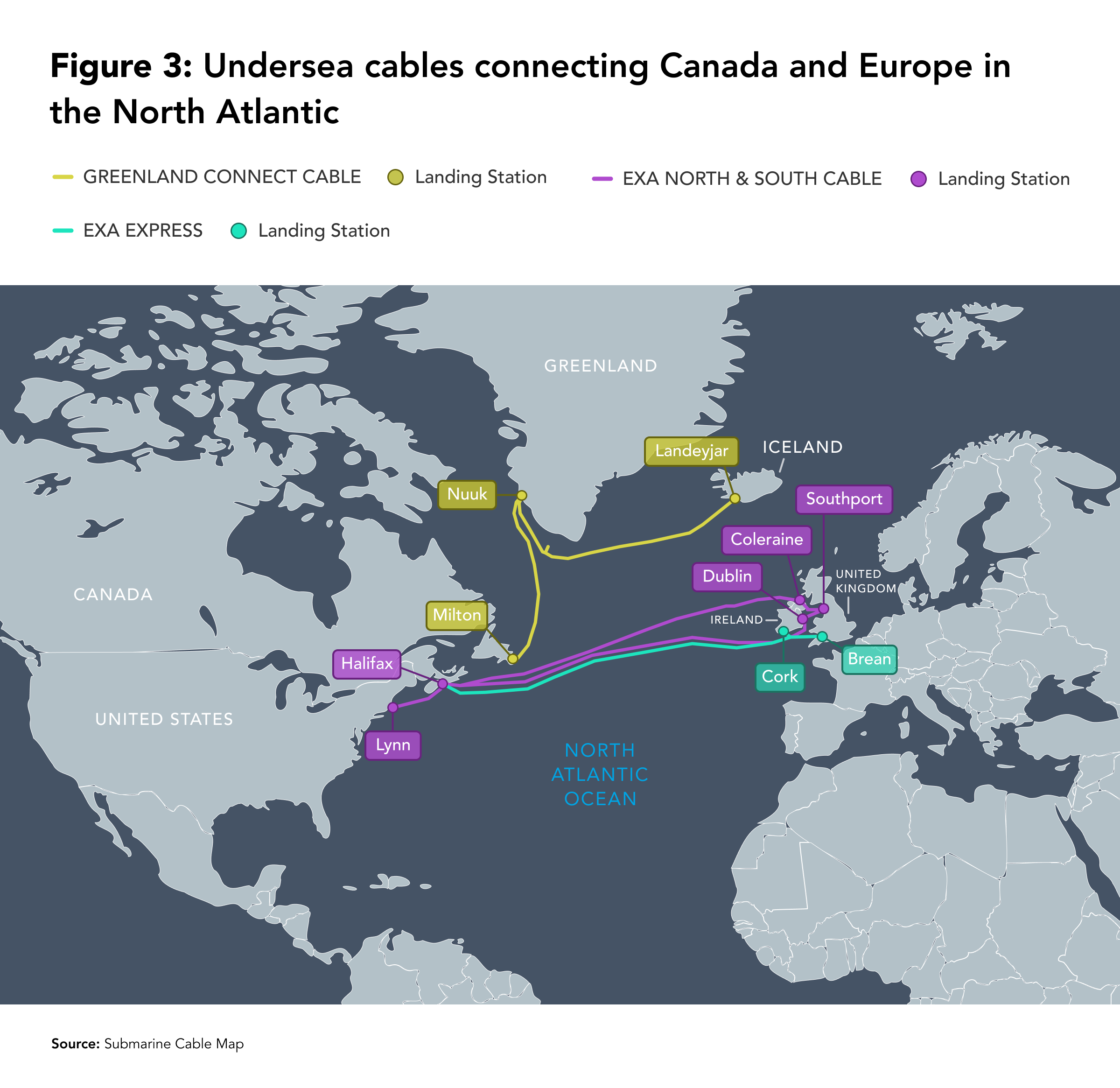

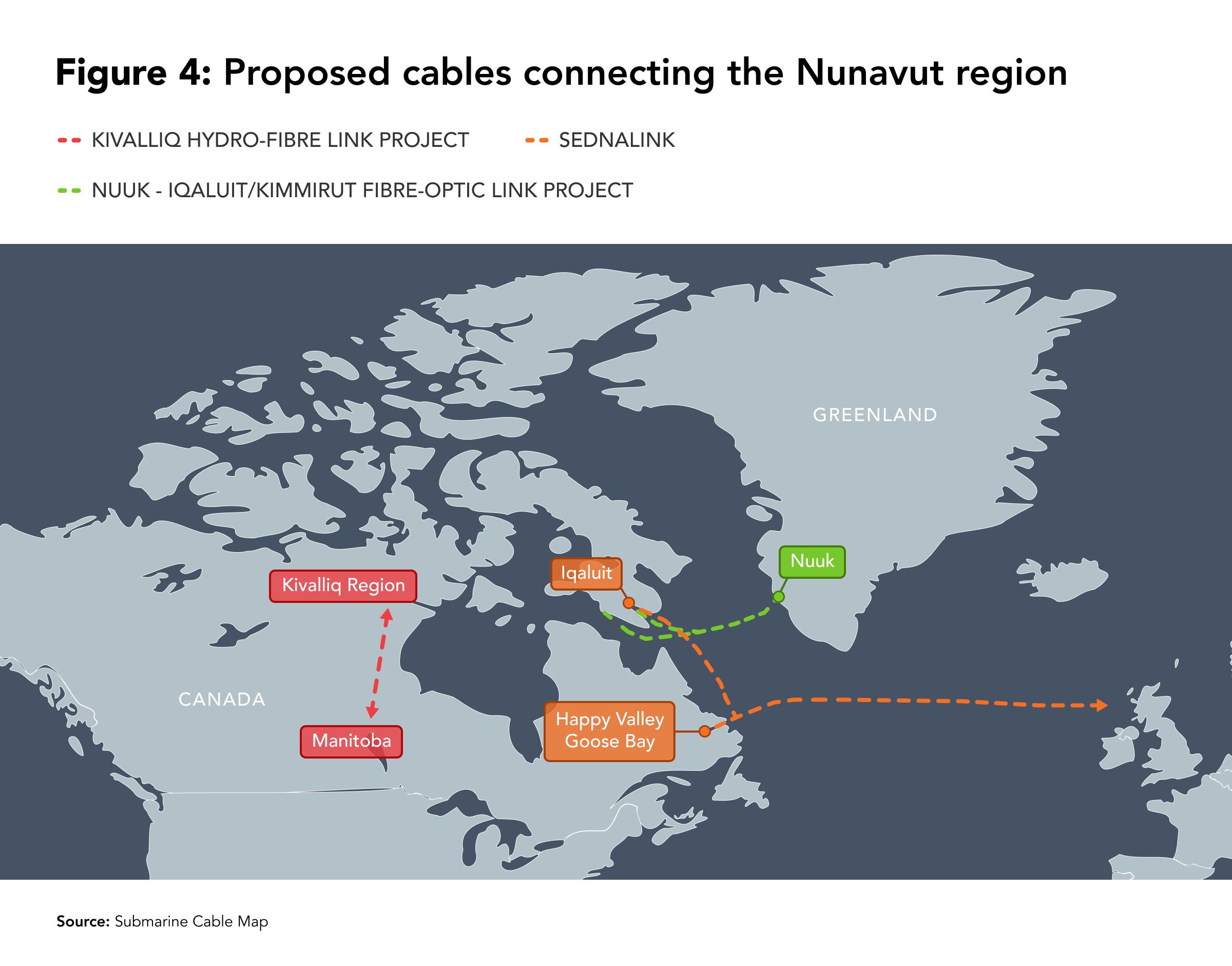

For Canada, with critical cables and pipelines already in service and new routes planned across the Arctic, North Atlantic, and North Pacific, grasping these protection challenges is vital. Strengthening resilience through cable redundancy (having multiple cables to ensure smooth connection even if one gets damaged) and improving maritime domain awareness through international co-operation will be key to safeguarding our undersea infrastructure.

Why is it so difficult to protect critical undersea infrastructure?

The more than 600 undersea cables carpeting the world’s oceans transmit more than 95 per cent of international data, including internet traffic, financial exchanges, and government communications. In addition, seabed pipelines carry vital oil and gas resources across maritime corridors. Together, these systems support digital connectivity, energy security, and advanced defence operations.

Despite its critical function, CUI is prone to damage by both natural disasters, such as earthquakes and typhoons, as well as human causes, such as anchoring and dredging by fishing vessels. Determining whether damage is accidental or intentional remains a major legal and technical challenge, which allows for malicious actors to attempt sabotage while avoiding accountability.

Private ownership presents an additional challenge due to conflicts of interest between commercial and state actors. Nearly all undersea cables are produced and installed by four private companies: SubCom (U.S.), Alcatel Submarine Networks (France), Nippon Electric Company (Japan), and HMN Technologies (China). While market-based incentives have resulted in high international connectivity worldwide in a relatively short period of time, this has also led to cables being clustered in key maritime chokepoints and geostrategic waters, complicating state-led efforts to conduct joint patrols and monitoring.

The difficulty in protection is also partly due to a lack of legal enforcement mechanisms, especially where jurisdiction in international waters is unclear or even contested. Existing frameworks, such as the 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables and Article 21 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, provide only partial safeguards due to a lack of specific regulations.

What do we know about recent cable cuttings around Taiwan and in the Baltic Sea?

Repeat cable cuttings pose a grave threat to Taiwan’s reputation as a leader in digital technology by normalizing the disruption of day-to-day activities that rely on secure telecommunications. In February 2023, two undersea cables connecting Taiwan and the Matsu Islands were damaged within a week of one another under suspicious circumstances reportedly involving a Chinese fishing trawler. The 14,000 residents of the Matsu Islands lost stable internet connection for more than 50 days, causing distress and financial loss due to halted e-commerce business and tourism disruptions.

Two recent cable cuttings near Taiwan are also notable for their illegal, coercive, aggressive, and deceptive (ICAD) properties. Chinese vessels often fly “flags of convenience” to hide their state of origin, and often turn off their Automatic Identification Systems, making them difficult to track. For example, on January 3, a cable off Taiwan’s northeast coast was found severed after a Cameroon-flagged Chinese cargo vessel was discovereddragging its anchor in an unusual pattern. This was followed by another incident on February 25, when the Chinese captain and crew of a Togo-flagged Chinese vessel were detained on the grounds of allegedly cutting a cable deliberately off Taiwan’s southwest coast.

Finally, recent incidents in the Baltic could be interpreted as test cases for a future hybrid attack on U.S.-allied NATO countries. Finland and Sweden, two states that joined NATO in 2023 and 2024, have been targets of CUI damage in recent years, suggesting that China and Russia may use cable sabotage to undermine the U.S.-led regional order.

How have Taiwan and Baltic states responded to cable cutting?

Governments have bolstered their efforts to protect CUI mainly by improving resilience, including investment in cable redundancy, developing legal frameworks to facilitate attribution, and seeking bilateral and multilateral platforms for co-operation with repair monitoring.

Taiwan, which currently has 15 subsea cables, plans to install at least two more in the first half of 2025. In addition, Taiwan is developing 700 satellite hotspots, and has been exploring a partnership with Canadian satellite operator Telesat. After designating subsea cables as critical infrastructure following the 2023 cuttings, Taiwan also installed a submarine cable automatic warning system (SAWS) on the Taiwan-Matsu cables and modified its Telecommunications Management Act, leading to heavier penalties for cable disruption. Following the January 2025 cable cutting, Taiwan also pledged to implement stricter inspections of foreign vessels.

For Taiwan, co-operation with regional security partners has primarily been bilateral. In January, Taiwan requested assistance from South Korea to investigate a Chinese vessel suspected of cable cutting before sailing to Korea’s port city of Busan. In addition to Japan’s official statement condemning the January 3 cable cutting incident, a Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force destroyer sailed through the Taiwan Strait for its first solo passage on February 5 in demonstration of Japan’s commitment to peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait.

In the Baltic, Germany has led the way in promoting awareness of CUI vulnerability, including by issuing a joint statement with Finland following a cable-severing incident in November 2024 that demanded a thorough investigation of the Chinese-owned vessel allegedly involved. What sets the Baltic region apart is that interstate collaboration is bolstered by institutional support through the European Union and NATO. The EU announced an Action Plan on Cable Security in February 2025, expanding on an earlier statement issued in 2024. In addition to establishing the Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cell in 2023, in January 2025, NATO launched the Baltic Sentry, a new security mission to combat sabotage of CUI.

Should Canada be worried?

Despite growing awareness, Canada’s current capacity to protect and respond to potential attacks on its seabed infrastructure remains limited. In November 2024, Bell Canada’s undersea cable between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland was damaged again after it was cut the first time in 2023. Although the RCMP concluded the cause was likely unintentional, the disruption exposed a blind spot in detection and response readiness.

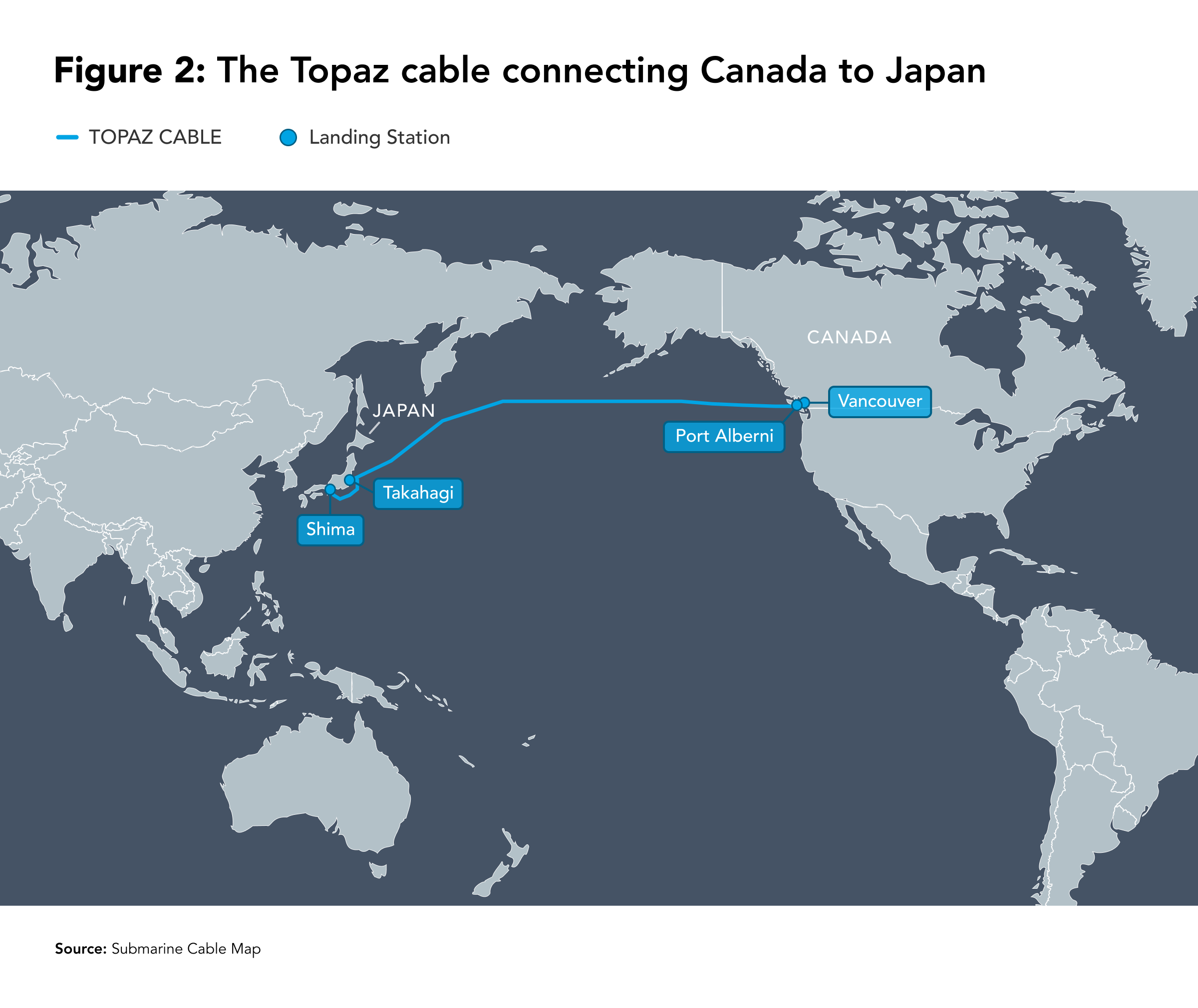

These risks are exacerbated by Canada’s dependence on privately owned infrastructure. As Canada’s only transpacific undersea cable, Topaz cable, is entirely owned by Google, Canada’s strategic connectivity in the Pacific may be undermined by private actors whose commercial interests may conflict with national security imperatives. In addition, Canada faces heightened risks due to the remoteness and limited surveillance capacity in the Arctic and the North Atlantic, where future cables, such as the SednaLink, are planned.

Furthermore, Indigenous communities — particularly in the Arctic — may be disproportionately affected. In Nunavut, for example, where connectivity challenges are persistent, the federal government recently announced funding for the Kivalliq Hydro-Fibre Link connecting the Kivalliq region of Nunavut to Manitoba, and a cable connecting Iqaluit, Nunavut, to Greenland. Both projects aim to expand broadband access and energy reliability. However, with completion dates projected as late as 2031, these initiatives remain in the planning and development stages. This stands in stark contrast to Indigenous communities along British Columbia’s coast that have seen tangible improvements in digital connectivity through the Connected Coast fibre-optic cable project.

What should Canada do to protect CUI?

Canada’s CUI is increasingly vulnerable to hybrid threats, ranging from cyber intrusions and signal disruptions to the potential sabotage of pipelines and undersea cables by foreign actors with growing ambitions in the Arctic. While partnerships with NATO allies remain a priority, Canada should also consider deeper engagement with like-minded partners in the Indo-Pacific, such as Japan and South Korea, who offer practical opportunities to enhance both technological resilience and strategic alignment. By integrating the protection of CUI in its 2022 Action Plan with Japan and its Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in 2022 with South Korea, Canada can tap into the world-class expertise of Japan and Korea in the production, deployment, monitoring, and repair of undersea cables.

So far, Canada has played an active role in building consensus and increasing global maritime domain awareness, including by participating in the G7 Joint Statement on Cable Connectivity for Secure and Resilient Digital Communications Networks in March 2024 and endorsing the New York Principles on Undersea Cables in September 2024. As the 2025 G7 chair, Canada has also led efforts to publish the G7 Foreign Ministers’ Declaration on Maritime Security and Prosperity in March, underscoring the need for international co-operation.

In addition to demonstrating solidarity through the G7, Canada could consider policy initiatives that focus on the Indo-Pacific region, such as joining the Cable Connectivity and Resilience Centre based in Australia, which was established as part of the Quad Partnership in 2023 to oversee the protection of CUI in the Indo-Pacific. Canada could leverage its longstanding defence partnership with Australia, its largest defence partner in the Indo-Pacific region, to gain technical assistance for maintaining Canada’s transpacific subsea cables and contribute to information-sharing and research-informed dialogues among Indo-Pacific countries.

Similarly, Canada can leverage its membership in the Five Eyes intelligence alliance and experience in dark vessel monitoring to contribute to a blacklist of suspicious ships that may have originated in China but use other states’ flags such as Cameroon and Togo to hide its original identity, and are often used for undersea cable cutting.

Finally, Canada’s continued naval presence in the Taiwan Strait, such as the passage of HMCS Ottawa on February 16 — the sixth since the launch of Canada’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy — is vital to signal Canada’s commitment to keeping the Taiwan Strait an international waterway.

While leveraging international partnerships can help close capability gaps, Canada must prioritize cable redundancy, particularly in hard-to-reach maritime zones. Targeted investments in the Canadian Coast Guard and repair vessels would allow for a rapid response in the case of sabotage. Indigenous communities should also be fully integrated into national CUI planning as geopolitical strategic competition intensifies in Canada’s three oceans.

• Additional Author: Mei Teresawa, Project Co-ordinator, APF Canada. Edited by Vice-President Research & Strategy Vina Nadjibulla and Senior Editor Ted Fraser, APF Canada.