Social media is playing an outsized role in the lead-up to the May 9 presidential elections in the Philippines. Government lockdowns and other COVID-19-related restrictions have made it difficult for candidates to hold in-person campaign events. These limits on large gatherings, combined with more than 90 per cent of Filipinos getting their internet access via social media, have meant that the candidates are heavily relying on social media to capture the attention and votes of the electorate.

These campaign conditions are happening against the backdrop of a longer-term trend in the Philippines: An accelerated shift away from traditional media and towards social media, where information may be free and accessible, but not always accurate. This new media landscape, however, is fertile ground for candidates and their supporters to turn increasingly to disinformation tactics on social media rather than traditional media techniques. In fact, many of the presidential candidates are reprising strategies that were leveraged to spread disinformation via social media in past election cycles, most notably the 2016 election, which brought current President Rodrigo Duterte to power. By allowing anyone to instantly share information with thousands of followers, social media accelerates the flow of information and does so in a way that disrupts the top-down hierarchies and editorial oversight imposed by traditional television and print media. This has had the cumulative effect of warping important national public discussions, including what is at stake for Filipinos in this upcoming election.

Facebook as game-changer

The introduction of social media in the Philippines has changed the information game in that country. Since 2013, Meta’s (née Facebook) Free Basics program has partnered with local carriers in the Philippines to provide Facebook to users at no cost. Requiring only a smartphone and a C$1 prepaid SIM card to facilitate internet access, Facebook has become the de facto internet for many Filipinos. By 2015, it had become the number one site used in the country. In 2016, the true impact of social media came to light during the national election in which then-candidate Rodrigo Duterte used social media to co-ordinate large elements of his campaign in lieu of traditional methods. Additionally, his campaign used social media bots on a large scale to intimidate his critics and promote pro-Duterte hashtags and pages to boost his popularity.

In response to the alarm raised by some in the Philippines, ahead of the 2019 midterm elections, Meta introduced new platform bans like the one on Twinmark Media Enterprises, fact-checking partnerships, and digital advertising rules to limit the type of disinformation that had been so prevalent in the 2016 election. Meta also took the initiative during the 2019 campaign season to remove accounts that engaged in “inauthentic behavior.” Here, inauthentic behaviour refers to online activities designed to be perceived as actions by a specific group when in reality, they are being done to mimic their actions. During an election season, it can be done to mobilize a specific political group with malicious intent.

Despite these changes, the Liberal party, the main opposition to Duterte’s Partido Demokratiko Pilipino–Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban) party, seems to have taken an “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” attitude and adopted some of the tactics that Duterte used during the previous election in an attempt to boost their own campaign. Meanwhile, social media use has continued to grow; as of 2021, about 81 per cent of the Philippines is on Facebook. And although the internet is notoriously slow in the Philippines, companies such as Facebook and YouTube, in particular, have made their platforms more convenient for sharing and consuming information.

Traditional media loses its lustre

The growth of social media is not the only significant development in the Philippines’ information space. While there are hundreds of newspapers and tabloids in the Philippines, the rise of social media has meant that nearly all of these traditional news media organizations have had to join and compete in the new platform ecosystems to survive. This has meant that due to strong financial incentives, company-made algorithms shape the “editorial sensibility and editorial investments” of the Philippines news media. This often translates into newspapers writing headlines with high shock value to increase engagement and ad revenues. However, external links are not included under Meta’s Free Basics, so individuals who rely on this program for internet access see only the out-of-context, incendiary media headlines but not the entire article that would presumably provide important context and nuance to the story.

While scholars long believed that television was the primary source of news and information for Filipinos, a 2017 survey showed evidence of a shifting media ecosystem, finding that Filipinos with internet access trust social media more than mainstream media. Another recent shockwave to the Philippines’ media landscape both reflected and further accelerated this shift: In 2020, Duterte and his supermajority in the Senate refused to renew the license of the nation’s most popular television channel, ABS-CBN, due to their allegedly biased and unfavourable news coverage, including of the president himself. And this year, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., the current frontrunner in the contest to be the next president, has shunned participation in any of the official televised debates, turning instead to non-traditional media to influence public discussion and public perceptions during this election cycle.

Disinformation in the current election

Already, similarities to the 2016 election campaigns are appearing with candidates using Twitter and aggressive, targeted hashtags in lieu of moderated debating. Two of the most popular hashtags are #KulayRosasAngBukas (an anti-BongBong Marcos tag) and #MahalinNatinAngPilipinas (support for Sara Duterte). There is also an attempt to modernize the different campaigns, with candidates relying heavily on social media websites like Facebook and YouTube to spread their various messages and engage with the electorate. However, this increased reliance on social media and negative strategies may backfire for some candidates as other candidates out-perform them by using these tools to become more popular. These other candidates can do so, for example, by building larger numbers of followers and engagement or with online ‘armies’ that target anyone they perceive to be a threat to their preferred candidate.

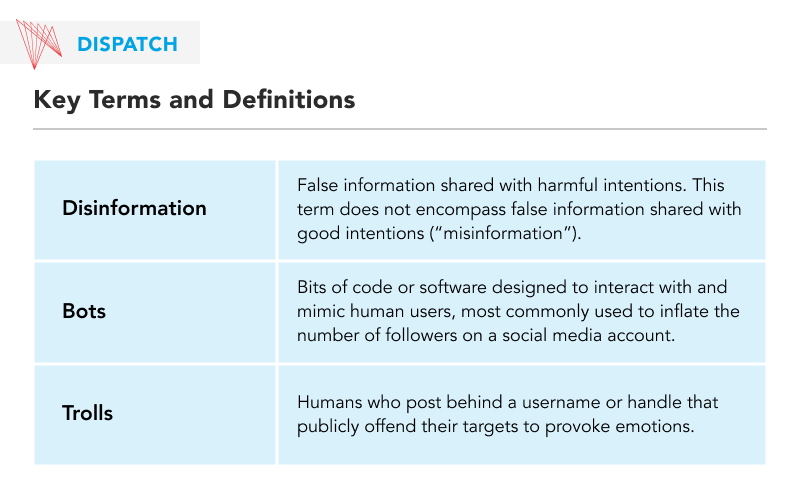

They can also do so through disinformation, defined as “information that is false and deliberately created to harm a person, social group, organization, or country.” As noted above, in the 2016 presidential election, disinformation was deftly used by the campaign of Rodrigo Duterte, with a combination of social media postings, trolls, bots, and online fan groups who engaged on his behalf, often using aggressive tactics.

These aggressive tactics often targeted high-profile women, such as current Vice-President and 2022 presidential candidate Leni Robredo. (The president and vice-president are separately selected through elections and thus sometimes come from opposing parties, as is the case with Duterte and Robredo.) Duterte’s personality and distinct public speaking methods increased his engagement, and his campaign also created easy soundbites that could be replicated and shared in multiple contexts. One example of this phenomenon is Duterte’s campaign promise to end homelessness six months after taking office, a claim that he quickly backtracked once elected. This combination of aggressive and ambitious campaign promises, social media posting, and online trolls soon became known as the “Duterte effect” – and these same tactics are in play in the 2022 presidential election.

Different responses to disinformation

In December 2017 and January 2018, the Philippines Senate Committee on Public Information and Mass Media held hearings on fake news in response to reports about Facebook removing posts about individuals related to the late President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. These two hearings focused on ways to combat fake news, misinformation, and disinformation. While the hearings intended to focus on the government’s role in spreading disinformation within the country, disagreements between senators derailed both sessions, hindering attempts to curb the spread of disinformation.

Fact-checking is one method that countries like Canada and the United States have adopted to combat disinformation. Since 2011, Rappler, an online news media organization based in Manila, has fact-checked politicians’ and public figures’ false claims. The Filipino government under Duterte, rather than embracing this endeavour, has pursued legal battles against Rappler and its CEO, Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Ressa. Rappler has published multiple pieces on Duterte’s use of disinformation and online trolls during his 2016 campaign, and Duterte’s government has accused the website of being a foreign entity that has a monopoly on the truth. Although Rappler is partially funded by Facebook, researchers widely regard the organization as an independent media organization.

The next Filipino government may continue in a hostile stance toward Rappler or adopt a more conciliatory posture towards the organization. But regardless, Rappler and other organizations engaged in fact-checking face an uphill battle: Because these fact-checking articles are less attention-grabbing, they often do not go as viral as the pieces of disinformation that they address due to algorithms that prioritize engaging content, meaning they often do not reach the people who consumed the original disinformation.

Recent developments and their impacts

In February of this year, the Philippines legislature passed an online abuse law to limit the spread of online disinformation in the country. The law requires social media users to register for a new account with their legal identities to help authorities trace the origins of abusive online behaviour. While the law aims to minimize the number of online trolls in the upcoming election, experts are divided on how effective it has been in practice. Some say it has, allowing fact-checkers and law enforcement to crack down on abusive behaviours online. Others, however, argue that this law will give the government new powers to target journalists and civil society.

The Philippines Commission on Elections (COMELEC) has taken active measures to pre-emptively tackle online disinformation. In February 2022, it verified a list of nearly 400 trustworthy YouTube news sources to ensure “the availability of trusted and credible sources of information for the public.” In early March, COMELEC signed a Memorandum of Agreement that cemented a partnership between Rappler and its fact-checking partners to conduct civic education, advertise the location of polling stations, and alert COMELEC about false and misleading election-related claims on social media. But due to political pressure and a subsequent court ruling, COMELEC suspended and then reneged on this deal at the beginning of April, returning to the status quo.

Social media companies have also taken a proactive approach to combating online misinformation and disinformation during this election cycle. In January, Twitter allowed users to flag tweets that contain misleading information, and in April, Meta suspended more than 400 accounts, pages, and groups for “coordinated inauthentic behavior.” However, some, like Rappler CEO Maria Ressa, believe that these corporations are not doing enough to prevent the flow of disinformation.

Moment of truth

The actual effects of the 2022 law and the effectiveness of these other efforts will be subject to scrutiny in the upcoming election, especially as social media is playing a more important role than ever in reaching voters and influencing their perceptions. COVID-19 restrictions, new platforms, and an increasing reliance on social media have shifted the dynamics of elections. The shift has also coincided with an increase in dangerous disinformation that has the potential to sway the opinions of voters. Understanding the actual impact of this shift will likely happen once the dust begins to settle after May 9.