In April, the news broke that Netflix will be “doubling down” on its South Korean content, investing nearly C$3.7 billion over the next four years to produce Korean TV series, movies, and reality shows. The investment comes at an opportune time; in Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, released in November 2022, South Korea is identified as an important partner for Canadian engagement in the region and “tightly connected through longstanding trade and cultural ties.” During Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s visit to Seoul in early May, Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly commented that the bilateral relationship is one between “good friends” and underscored the need to strengthen Canada’s ties with South Korea.

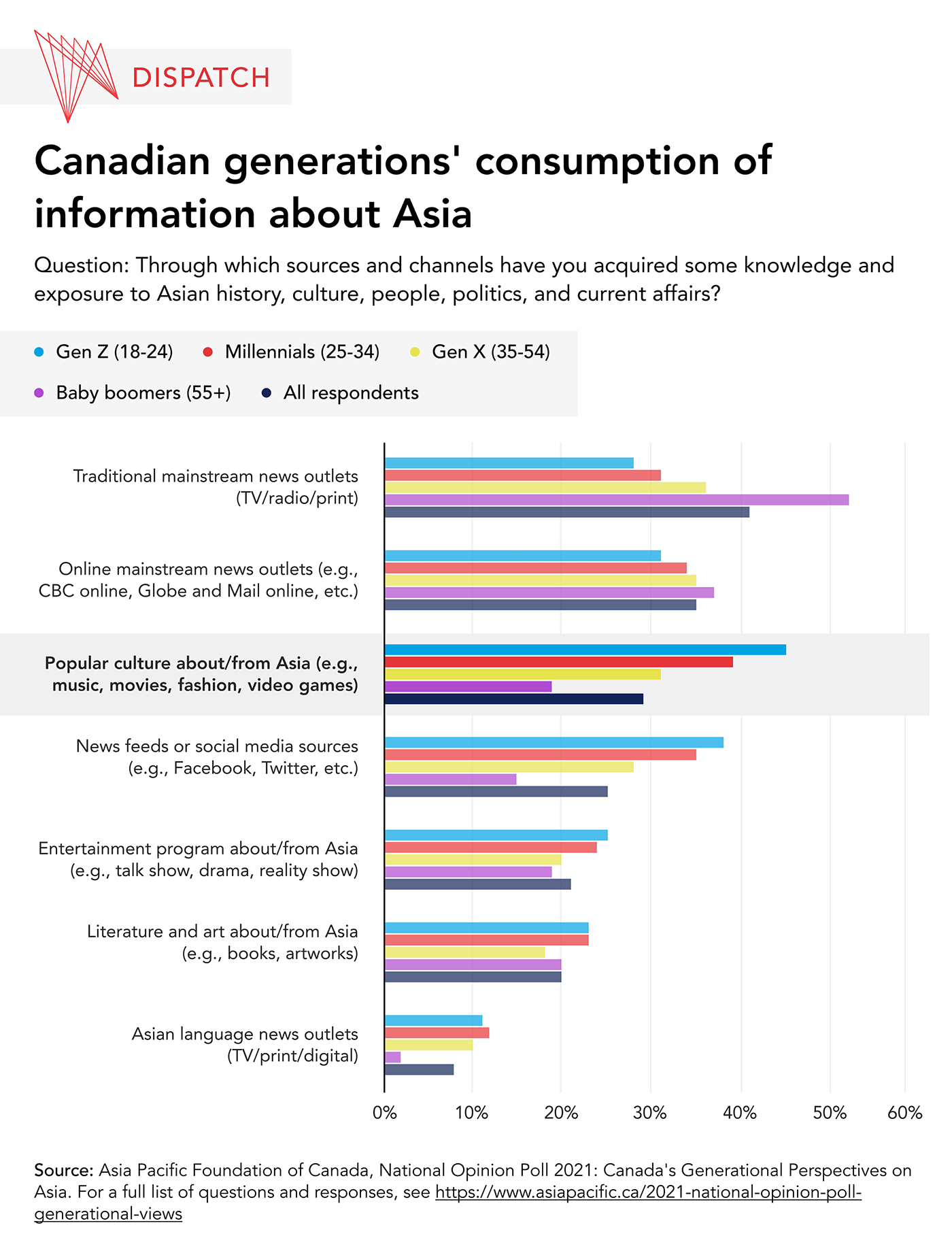

In strengthening those ties, Canadians would benefit from a deeper familiarity with South Korean culture and society — and one way to do that is through film. According to a 2021 National Opinion Poll by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada, 45 per cent of Gen Z Canadians (26 years old or younger) get most of their information about Asia from popular culture, more than any other information source (see graphic, below). Some forms of popular culture, such as music and video games, are primarily entertainment-based. But films, in particular, can be a rich source of insights into societal issues. That is certainly the case with South Korea, where the most successful movies highlight important social issues and are a useful barometer of the national mood.

South Korean cinema, as international audiences know it today, got its start in the late 1980s and early 1990s, following a gradual decrease in political censorship in the country. Since then, South Korea has produced some of the world's most interesting and popular movies. A recent example is Parasite, which won Best Picture at the 92nd Academy Awards in 2020 and stimulated a conversation about class politics and severe wealth inequality in South Korea. But Parasite was not the first film to introduce international viewers to such issues. The five films highlighted below provide a good introduction to a side of South Korean society that Canadians (and other Westerners) do not always see.

Oldboy

When Oldboy premiered in 2003, it was an instant hit, winning the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004. It would go on to achieve considerable commercial success, earn praise from international and domestic critics, and cement South Korea’s status as a film industry powerhouse. At its core, Oldboy is a revenge thriller and mystery about a man imprisoned for 15 years before suddenly being released. Unfolding on the streets of Seoul, the movie traces the man’s brutal quest for revenge against the people who imprisoned and then released him with no explanation, culminating in a set of stunning revelations.

Interwoven between moments of extreme violence and shocking discoveries is a larger, overarching story of poverty, inequality, and the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) of 1997. While imprisoned, the man learns about the outside world through a television that relays a range of news stories, including former president Chun Doo-hwan’s arrest on corruption charges, the disaster of the Seongsu Bridge collapse in 1994, and multiple stories about the AFC, which was caused by a series of currency devaluations and led to a financial emergency. While the International Monetary Fund provided South Korea with a bailout, it also imposed strict spending requirements that led to economic hardships and widened the country’s wealth gaps.

The Host

In 2006, The Host became South Korea’s biggest domestic box office success and remained the most-seen movie in the country until it was edged out by Avatar in 2010. At its core, The Host is a monster movie that begins with a member of the U.S. military ordering his Korean assistant to dump chemicals into the Han River, which runs through the capital city of Seoul. This act sets in motion a series of events that leads to the emergence of a horrific monster that terrorizes a riverside community.

The Host took its inspiration from recent history and a national mood of frustration following the McFarland incident of 2000, when a U.S. soldier stationed in South Korea ordered Korean employees in his charge to dump liquid formaldehyde into sewage systems that eventually wound up in the Han River. When news of the incident went public, it sparked a backlash and revealed widespread frustration with the actions of U.S. forces stationed in the country.

Train to Busan

Train to Busan first premiered at the Cannes Festival in May 2016 before opening domestically in July 2016. The film dominated the box office and shattered records for ticket sales.

The film's central premise is a familiar one: a massive zombie outbreak overwhelms a government, forcing survivors to flee to designated ‘safe areas.’ The story follows an overworked businessman taking his daughter by train to the southeastern city of Busan to see her mother. The pair is joined by a group of other passengers who are terrorized by a zombie onboard the train. The rest of the film follows the group fighting the zombie while navigating interpersonal conflicts.

Although not as explicit as The Host, Train to Busan is a social commentary that includes a monster element. The film was released two years after the sinking of the ferry MV Sewol, which resulted in the deaths of over 300 passengers — most of whom were high-school students — after crews loaded twice the legal weight limit for cargo onto the boat. Subsequent investigations uncovered corruption at every level.

In Train to Busan, the zombie plays the role of antagonist rather than a villain; the villains, in this case, are the other passengers. Throughout the outbreak, as the survivors move through the train, their progress is hampered by businessmen who protect themselves at the expense of others. However, by the end of the film, when the characters recognize the human cost of their actions, they change their behaviour to prevent additional deaths. It is such changes in behaviour – away from self-preservation to doing what benefits the larger community – that the public was calling for at the time of the MV Sewol tragedy.

Broker

Broker was released internationally in January 2023. The movie follows two church volunteers who sell babies left in church-run ‘baby boxes’ to wealthy families. One night, a baby is left in one of these boxes with a note from his mother saying she will return for him. However, the two volunteers, who have seen such notes before, assume the mother will not return and prepare to sell the baby to a family (rather than place him in an orphanage). In a twist, the mother does return, but is eventually persuaded to help the two volunteers find a different family to raise her son.

The timing of this film is significant. South Korea held a presidential election in 2022, with conservative candidate Yoon Suk Yeol defeating liberal candidate Lee Jae Myung by a margin of less than one per cent. One of Yoon’s key campaign pledges was to abolish the country’s Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. The ministry played a key role in moving the issues of gender and family to the centre of policy discussions and has overseen a wide range of programs, including support for single parents and child care. While Yoon has not yet disbanded the ministry, his pledge to do so follows several years of controversial gendered policies in South Korea that have had problematic results for mothers and reflect a growing and increasingly negative discourse, namely, (false) claims that sexism is a thing of the past and that feminism is the cause of the country’s declining birthrate.

Broker reflects — while also challenging — this discourse and the consequences for single mothers. In the film, both the volunteers and the police express the view that single mothers are irresponsible and put forward the traditional family as the ideal environment for a child. However, as the movie progresses, this idea is subtly challenged, including through the experiences and choices of the single mother. While the film does not make a value judgement about which type of family is ‘best,’ it presents a compelling argument, balancing the widely negative discourse in South Korea around gender issues.

All five of these films and their overarching themes and narratives tend to run counter to the soft power images put forward as part of South Korea’s official cultural diplomacy. While cultural diplomacy and a country's national image are important, they can also obscure social issues below the polished surface, giving international audiences an incomplete picture of a country.

These South Korean films help bridge that gap between image and reality, presenting difficult themes and subjects in the form of highly engaging films with high-quality storytelling and innovative filmmaking. As Canada forges deeper cultural ties with South Korea as part of its broader engagement strategy in the North Pacific, Canadian audiences have a unique and – thanks to Netflix and others investing heavily in Korean content – expanding opportunity to explore films that open a window on a country that will only increase in importance in the coming years.