The “Chinese debt trap” narrative has gained traction in recent years among pundits and observers of China’s international affairs. The central premise is that many of China’s international infrastructure builds (i.e. the ‘Belt and Road Initiative,’ or BRI) and its foreign development loans drive debt distress in developing countries to gain geopolitical leverage.

A central driver of this narrative is the fact many countries that have received Chinese financing are now facing dire economic circumstances, drawing global attention to the weaknesses in their economies. Proponents of this view often point to Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, which was surrendered to China on a 99-year lease after Colombo was unable to make debt repayments. Others, however, say the ‘debt trap’ is a myth, an oversimplification painting a binary picture of China as an evil lender and the borrower as an unsuspecting victim. Laos is one such case that highlights these issues.

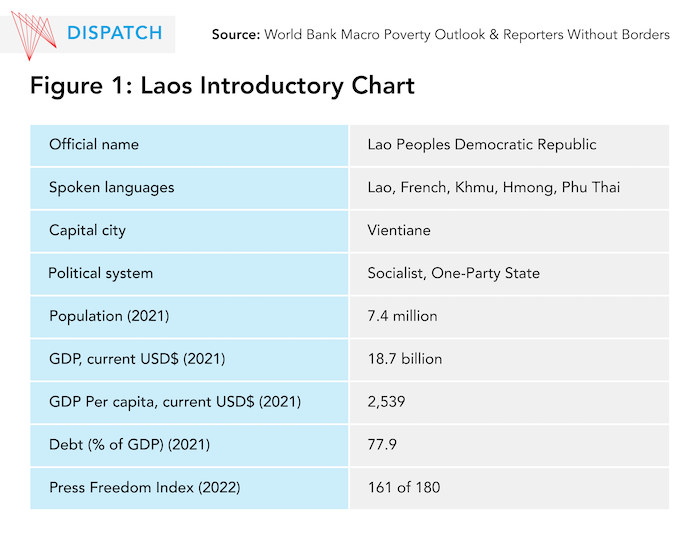

As a one-party state with severe restrictions on press freedoms, Laos’s economic activities are often shrouded in secrecy. In recent months, the Laotian government has repeatedly downplayed suggestions that the economy is in trouble. But many observers are not convinced, comparing Sri Lanka — which declared sovereign default in April 2022 — to Laos. Laos’s sharp currency depreciation and surging inflation have exacerbated its existing macroeconomic problems of debt accumulation (mainly owed to China) and sparse foreign reserves. Some observers argue that this is a case of a Chinese “debt trap” in Laos, partly caused by the steep costs of several large China-funded infrastructure projects, including the Lao-China Railway and several hydropower plants. While Laotian President Thongloun Sisoulith says his country hasn’t fallen into a Chinese debt trap, the argument appeals to many Western audiences.

The case of Laos shows that the reality is much more complex, as borrowing countries have significant agency, and China has shown to be accommodating when it comes to debt repayments. However, there are valid reasons to look more closely at such lending arrangements. For example, a recent study of Chinese debt contracts illustrates patterns in China’s official lending practices, which often include far-reaching confidentiality clauses and novel terms that may influence debtors’ economic and foreign policies. Understanding the fine print of these arrangements, especially as allegations of Chinese debt traps grow, is important. This is true for Canada, which, in its recent Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS), identifies an estimated “C$2.1-trillion opportunity for strategic investments and partnerships” in the region’s infrastructure sector.

Surging inflation, diminishing reserves . . . and potential default?

Experts began sounding the alarm as Laos’s existing economic challenges were exacerbated by the fallout from COVID-19 and the Russia-Ukraine war, including its high consumer prices, rampant inflation, and declining foreign revenue from tourism. From January to October 2022, the Lao kip depreciated 68 per cent against the U.S. dollar, and the country's year-on-year inflation reached a 22-year high of 39.3 per cent in December 2022. This placed a significant strain on the livelihoods of Laotians, including the need to line up for hours to buy gas. Some even travelled to neighbouring Thailand for euphemistically labelled “fuel tourism.”

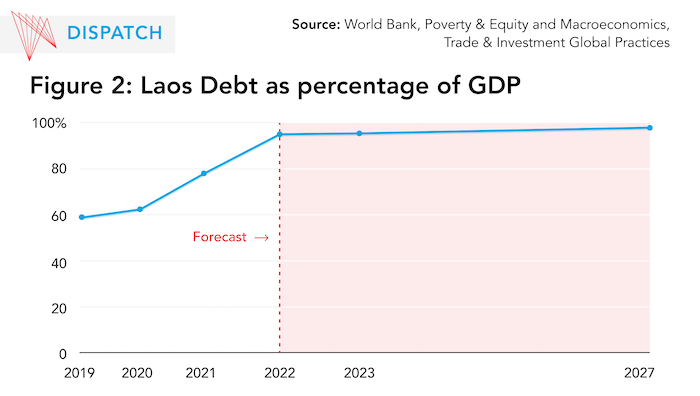

Although the government was able to stabilize the currency and respond to the gas shortage through a government credit line, many international observers expect that the long-term impacts of such responses will be limited due to structural weaknesses. These include the lack of liquidity in the state budget, a high debt-to-GDP ratio, weak government controls on goods, ineffective tax collection mechanisms, high trade deficits, and most notably, the country’s low sovereign credit rating due to rising debt, which would further reduce the country’s access to international financial markets.

In October 2022, Fitch assigned Laos a long-term foreign currency issuer default rating of ‘CCC-,’ which indicates “substantial credit risk,” making default “a real possibility.” World Bank statistics show a rapid growth of Laos’s debt-to-GDP Ratio, from 59 per cent in the 2019 fiscal year to 95 per cent in the 2022 fiscal year. However, researchers suggest that the country’s foreign debt is significantly higher due to “hidden” public debts. These hidden debts would be excluded from official statistics due to the lack of a sovereign repayment guarantee (a government’s guarantee to satisfy the debt obligation) but contracted by entities owned or partially owned by the government. In the 2021 fiscal year, figures including the “hidden” debt estimated that Laos’s debt exposure could reach up to 120 per cent of the country’s GDP.

Laos will have to repay an estimated annual debt of US$1.2-1.4 billion for five years – half of which is owed to China – despite its low foreign reserves, which stood at US$1.075 billion in September 2022. While significant debt relief has been granted since 2020, especially from China, other creditors such as Thailand may not be as forgiving, and Laos will have to find long-term, sustainable solutions for debt repayments. To this end, Laos is hoping to become a large hydropower exporter, especially as the regional demand for clean energy is expected to rise. However, such ambitions may be hampered by environmental, human, and economic costs.

The economic, political, and environmental costs of hydropower

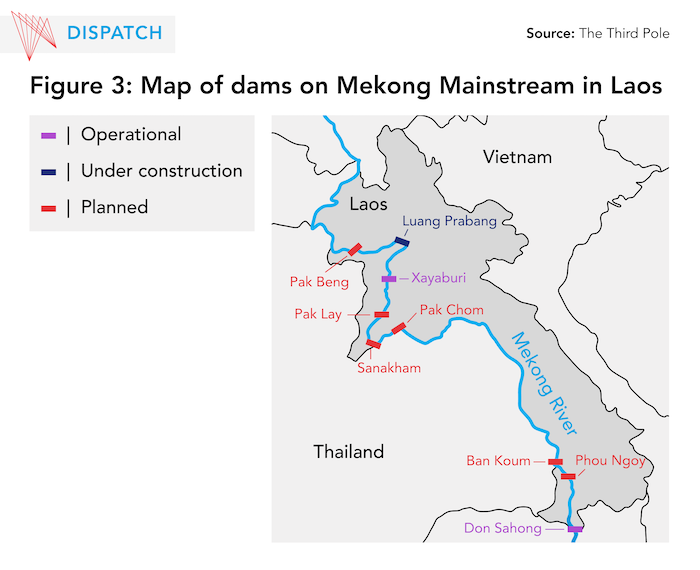

In the early 2000s, Laos set out to become the “battery of Southeast Asia.” As one of the poorest and least developed countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the country saw an opportunity for rapid economic development through hydropower, hoping to tap into the Mekong River and its major tributaries, which flow through and around Laos. This water system is not only a lifeline for Laos and other countries in the region, but a much-needed source of energy. Within a decade, Laos’s hydropower capacity increased exponentially, from 400 megawatts in 2000, to approximately 7,000 megawatts in 2022. Today, Laos has 78 dams in operation, with an additional 246 memorandums of understanding for other hydropower projects. There are currently two major dams in operation on the Mekong River, with one more under construction and six dams slated for development.

Although Laos has rapidly accumulated foreign debt, the government believes in the future of hydropower, which will become essential as ASEAN countries seek to meet international climate obligations. ASEAN’s energy demands are expected to grow by 60 per cent over the next two decades, and Laos sees itself as well-positioned to provide affordable and clean energy to its more industrialized and globalized neighbours.

Hydropower may indeed be a force for positive change for Laos, but it poses significant costs. Laos’s economic gains have been stunted due to inconsistent water supply and a lack of real demand from potential customers. The construction and operation of hydropower plants also comes with significant environmental and human risks, especially for the 70 million people in mainland Southeast Asia, who rely on the Mekong River for their livelihoods. The country’s increasing debt, combined with global economic pressures, has also severely impacted domestic economic activity, prompting pundits to question the long-term sustainability of Laos’s hydropower ambitions.

Is China debt-trapping?

As Laos’s debt increases and its economic recovery sputters, the country’s heavy reliance on China, not only for funding but also for the steady flow of water from eight major upstream Chinese dams, have strengthened accusations against China that it has “trapped” Laos.

Although Chinese “over-lending” may have contributed to Laos’s debt problems, singling out China as the sole culprit is an oversimplification. Several dam projects have also been funded by countries such as Japan and France, while the recently opened Lao-China Railway may have positive effects on Laos’s economic recovery. However, the lack of information and transparency behind China’s lending has allowed for cherry-picked evidence to be used to bolster suggestions that China is debt-trapping Laos.

For example, in March 2021, Laos signed a 25-year concession agreement that gave a majority-Chinese company the rights to build and manage power grids in the country. Although the power grid development project is a joint venture between Laos and China, Laotian officials have stated that they do not “have the ability to manage and operate the powerlines,” citing the large foreign debt and domestic economic problems, while praising China’s “finances, technological aptitude, and manpower.” Similarly, in September 2021, Laos and China celebrated the opening of the Nam Ou hydropower project in the country’s north, consisting of seven plants developed by the Power Construction Corporation of China under China’s BRI. This US$2.8 billion investment also comes with a concessional agreement, allowing China to operate the dams for the first 29 years.

Despite perceptions that these are examples of China debt-trapping Laos, most Laotian officials view the projects as opportunities to build the infrastructure needed to pursue their longstanding goal of becoming a major energy exporter to generate foreign income. Laotian officials say such concessions to China are a necessary measure due to the grave economic situation facing the country. China’s strong geopolitical interests in Laos, combined with extensive financial investments by Chinese investors and the political relations shared by the socialist leadership of the two countries, have resulted in China instead having protective policies towards Laos. Nishizawa Toshiro, former advisor to the government of Laos, has argued that China would never let Laos go into default over external debt obligations for the abovementioned reasons, rejecting a major part of the Chinese debt-trap argument.

Rising regional competition, infrastructure investments in ASEAN

Although the European Union and the Group of 7 (G7) have recently created their own global infrastructure initiatives to rival China, the reach and expertise of Chinese infrastructure development is immense. As China is increasingly perceived as a “disruptive force” against the rules-based international order, global security interests are shifting towards the Indo-Pacific, with ASEAN at its core.

Canada has also emphasized its renewed focus and interest in ASEAN through the release of its IPS and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s participation in the ASEAN Summit in mid-November 2022. Within the IPS, Canada has identified the Indo-Pacific’s growing infrastructure funding gap, which they will seek to seize for Canada’s economic security. Combined with its new commitments to ASEAN centrality, Canada has the opportunity to strategically and holistically engage with Laos and contribute to creating a sustainable future.