Climate disasters such as droughts and flooding have increased the urgency of decarbonization — that is, the reduction of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere. The Asia Pacific region is central to these decarbonization efforts. A recent report by PricewaterhouseCoopers notes that in 2020, the Asia Pacific was responsible for 52 per cent of global CO2 emissions. The report anticipates that emissions could continue rising as the region’s demand for energy (in the form of fossil fuels) increases.

Current decarbonization efforts are already straining supplies of critical minerals, key inputs for clean energy technologies, such as solar and wind energy generators and electric vehicles (EVs). The global push towards decarbonization is, moreover, “trigger[ing] a race to secure uninterrupted access to critical raw minerals.” The Economist predicts that mining companies will need to increase their output of critical minerals, such as copper and nickel, by 500 per cent in the coming decade to meet the impending demand.

Canada is well-positioned to help meet this rising demand by becoming a reliable mineral supplier to key markets in the Asia Pacific. Two of Ottawa’s recently announced strategies — the Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) and the Critical Minerals Strategy (CMS) — envision stronger trade and investment ties between Asian economies and Canada in critical minerals.

China, for one, is a sizeable regional market for Canada’s critical minerals, and Ottawa should continue to export resources to the country, while expanding exports to other regional economies in its pursuit of a diversified trade strategy. As Canada seeks to diversify its partners in the critical minerals sector, the government will need to reconcile two requirements. The first is finding reliable economic partners to purchase Canada’s critical minerals. The second is addressing national security concerns stemming from foreign direct investment (FDI), especially when investments come from state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which may be guided by non-commercial motives.

Canada’s Critical Minerals Policy

In December 2022, the Canadian government launched the CMS to develop critical mineral value chains domestically and establish secure critical mineral supply chains abroad. The CMS focuses on 31 critical minerals, including lithium, nickel, and graphite, which are essential for the production of EVs. According to the strategy, these critical minerals are “essential to Canada’s economic security,” as they contribute to the country’s “transition to a low-carbon economy” and act as “a sustainable source of critical minerals for [Canadian] partners.”

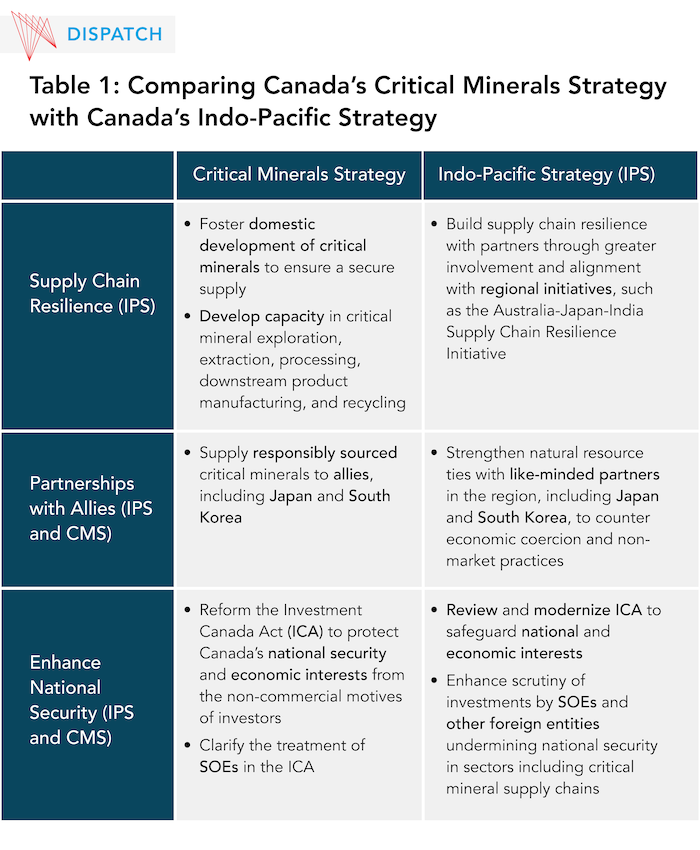

In the Asia Pacific, the CMS is strengthened by the IPS, which was released in November 2022. Through the CMS and IPS, Canada will diversify its investments and trade partnerships in critical minerals by tapping into international supply chains and partnering with like-minded regional economies (Table 1). The resilience of the global critical mineral supply chain and Canada’s ability to supply critical minerals internationally will depend on the domestic development of critical minerals, which requires substantial investments.

Both the CMS and IPS acknowledge that foreign investment will be required to develop Canada’s critical minerals industry, but also that there are national security implications related to investment from SOEs. Although both strategies are ambitious in diversifying Canada’s trade and investment partnerships, their implementation will need to reconcile the two requirements in Canadian trade and investment partnerships in the Asia Pacific (finding reliable partners and addressing national security concerns).

Charting a Course for Canada’s Critical Minerals Exports

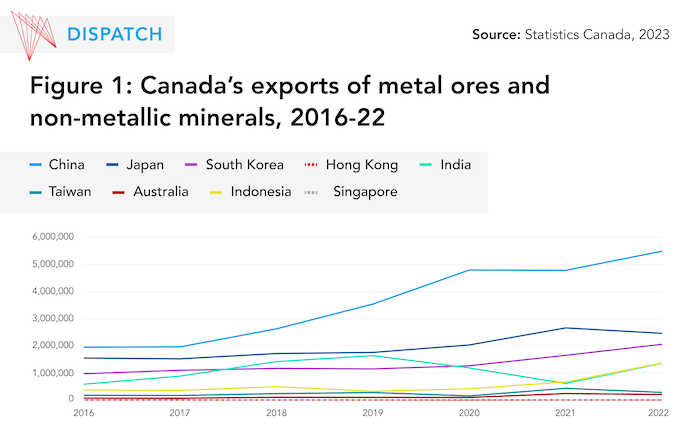

Both the IPS and CMS identify Japan and South Korea as regional allies and reliable trade partners. According to Statistics Canada, both economies increased their imports of Canadian minerals from 2020 to 2022 (Figure 1). Given recent political developments — a new memorandum of understanding on critical minerals with South Korea and a renewal of Canada’s commitment to supply critical minerals to Japan in 2022 — both economies are expected to continue increasing their imports of Canadian critical minerals.

Nevertheless, Canada’s mineral export volumes to these two markets are well behind those of China — Canada’s largest regional export market. China is also the largest consumer of Canada’s minerals in the Asia Pacific region, accounting for seven per cent of Canada’s global exports of minerals. Canadian exports of minerals to China in 2021 alone were valued at C$9.4 billion. Among Canada’s top mineral exports to China were iron ore and copper, which are important minerals for decarbonization efforts, with the former used in the construction of steel structures and the latter used for electricity-related technologies. Given that China represents a large market for Canada’s critical minerals, Ottawa should continue to export resources to China while diversifying and increasing exports to other economies.

India may be a good alternative export market. The country’s demand for Canadian critical minerals has rebounded as part of its post-pandemic recovery and is expected to increase, driven by rising demand for EVs, a desire to reduce CO2 emissions, and its “Make in India” and “Smart City” programs that will rely on commodity imports, including critical minerals. As India seeks to increase its renewable energy production by 2030, its demand for critical minerals, such as lithium and nickel, is expected to grow over the next few years.

To expand the Canadian footprint in India and other regional markets, the federal government should examine strategies adopted by other critical mineral exporters in the region, such as Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy. As indicated in Australia’s Global Resources Statement, the country aims to strengthen its relationships with regional partners on critical minerals and establish Australia as a “reliable supplier of energy resources and critical minerals to new and existing trading partners” in the region. The strategy is complemented by trade agreements that eliminate tariffs on critical minerals under the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement and the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (China being the largest consumer of Australia’s commodity exports). Canada has a precedent for this practice in its free trade agreement (FTA) with Chile and could consider incorporating critical mineral tariff reductions into current FTA negotiations with ASEAN and India as well as in CEPA negotiations with Indonesia. The elimination of tariffs on trade in critical minerals may boost exports, allowing for a domestic expansion of the sector and market diversification in the region.

National Security Implications

The CMS and IPS nudge Canada toward reforming the Investment Canada Act (ICA), which is designed to review “significant investments in Canada by non-Canadians.” The Act encourages FDI that benefits the Canadian economy and restricts investment that may be harmful to Canada’s national security. Referencing the ICA, the IPS notes that Canada should act “decisively when investments from state-owned enterprises and other foreign entities threaten [Canadian] national security.” The IPS reflects the federal government’s cautious stance on foreign SOEs, including subjecting them to more stringent investment reviews than non-state companies due to their close connections to their home governments.

Studies suggest that SOEs may be politically motivated and, as a result, may undermine the national security of host states. These SOEs may seek to acquire technology in support of their home country’s industrial policies or acquire natural resources abroad to meet domestic needs. National security concerns in host economies are especially elevated when potential investments come from SOEs based in countries that compete with host states, as in the case of Canada and China.

Ottawa has already released guidelines on Foreign Investments from SOEs in Critical Minerals to discourage such investments. The shifting geopolitical environment and increased national security concerns are reflected in the government’s decision, announced in November 2022, to mandate divestments of three Chinese state-connected entities. The decision can be traced back to The Neo Lithium Acquisition report, released by the Standing Committee on Industry and Technology in March 2022, which demonstrated growing unease among policymakers and stakeholders about foreign SOE investments in Canada’s critical minerals sector. The report recommended that FDI from SOEs from authoritarian regimes be closely reviewed, especially in priority sectors such as critical minerals, and prompted the government to develop a comprehensive Critical Minerals Strategy. But by rejecting investment from all government-connected enterprises, Canada will limit the pool of investors interested in acquiring Canadian critical mineral assets.

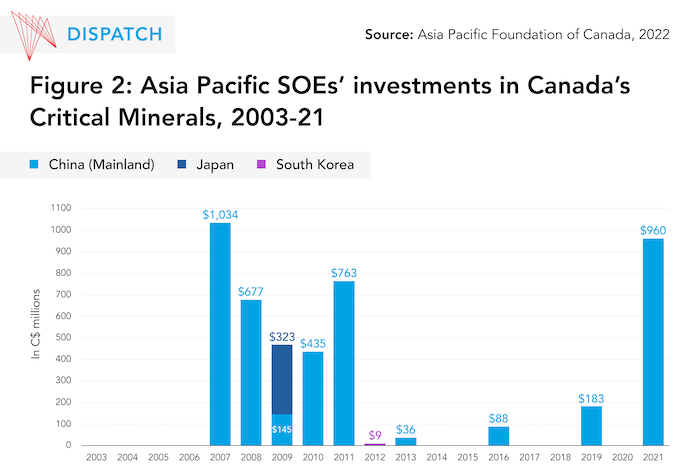

The Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s recent Investment Monitor report indicates that from 2003 to 2021, SOEs were responsible for almost one-quarter of all Asia Pacific FDI in critical minerals (C$4.7 billion). Most of these investments (C$4.3 billion) were made by Chinese SOEs, with SOEs from Japan and South Korea accounting for the rest of the investment value. Since SOEs are common in the Asia Pacific, restricting FDI by SOEs may limit capital inflow from friendly Asia Pacific countries. Such restrictions may also impact investments made by SOEs with which Canada partners in the region, such as Japanese Tokyo Electric Power Co. In such an environment, SOE investments in critical minerals could very well come to a standstill.

Moreover, if Canada restricts investment from SOEs, the government is closing the door to ‘patient capital’ — that is, investment that is not interested in earning quick profits and would remain even during economic downturns. Certainly, safeguarding national security is essential for Canada’s economy, but the decision to close critical minerals to all SOEs indiscriminately may reduce investment by SOEs from favourable economies. Several emerging economies in Asia have SOEs, and not all behave the same way. The blanket restrictions on SOEs may turn away patient capital from SOEs that would otherwise support Canada’s objectives, making it important to consider such investments on a case-by-case basis. As Canada seeks alternative partners in the region, Ottawa’s SOE strategy should be cautious but flexible enough to allow productive investment that does not undermine Canada’s national security.

The Way Forward

Critical minerals are a generational opportunity for Canadian businesses. As such, they must be integrated across Canadian strategic planning. Supported by the CMS and IPS, Canada can become a reliable global supplier of critical minerals, EVs, and EV batteries. Canadian businesses will benefit from CMS funding, which will allow them to expand their operations domestically, while the IPS could increase international collaborations in the sector. The shifting global geopolitical situation will undoubtably give rise to new international collaborations, creating new opportunities for Canadian critical minerals as countries seek to reduce their dependence on a single supplier and diversify their supply chains to a network of ‘friendly’ suppliers, as demonstrated by the U.S.-led Minerals Security Partnership. Ottawa's recent decision to limit investment from state-owned and state-connected entities, which may not have Canada’s best interests at heart, will also restrict Canada's ability to collaborate with like-minded regional business partners that are linked to any foreign government. Navigating these shifts in politics and policy atop the choppy seas of current global geopolitics will require careful balancing and a case-by-case approach to ensure that Canada’s objectives in developing critical minerals are met, but not at the expense of national security.